chadn737

Senior Members-

Posts

506 -

Joined

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by chadn737

-

Natural and Optimal Human habitat/habitats?

chadn737 replied to Anopsology's topic in Evolution, Morphology and Exobiology

No, there is not a natural human habitat. To some extent, humans have evolved for many habitats. In Tibetan peoples, there are strong signals of natural selection in the genome for survival at high altitudes, indicating an example of local adaptation. By this logic then, the Himalayas are the natural habitat of the Tibetans. There have been recent trends to try and live life styles based on our evolutionary history, the idea being that this is the secret for healthy living. Hence the paleo-diet. The problem with this logic is that evolution does not select for long healthy lives or harmonious ones with nature. It selects for reproductive success. Ancient man typically died at a young age. He was plagued by disease, injury, and many maladies. We never evolved to live to 70 or more. One can live a harmonious life anywhere, whether the arctic or an island paradise. -

Help - a question on new species

chadn737 replied to julianm's topic in Evolution, Morphology and Exobiology

It depends on how we define reproductive isolation. There are three different types of speciation that are determined by geography and the degree of migration between populations. Allopatric speciation does result from reproductive isolation. A population becomes split and reproductively isolated from each other by geography. Say, if you colonize an island and are then cutoff from the original population. These isolated groups then evolve along separate paths. Parapatric speciation occurs when two populations occupy distinct geographical spaces, but migration and interbreeding between the two still occurs. Sympatric speciation occurs when the two diverging populations occupy the same geographical space. In Allopatric speciation, there is a clear reproductive isolation by geography. The question then is how do you get speciation in a sympatric scenario? The problem is, that occupying the same geographic space, its very easy for individuals to interbreed. Therefore you get gene flow between the populations, which maintains allele frequencies and thus preventing speciation. However, geography is not the only means of reproductive isolation. For instance, when individuals reproduce could be of importance. Think of a plant. It normally flowers in the spring. A mutation arises that causes it to flower in the summer, separating its flowering time from the rest of the population by months. Because they flower at different times, this creates a barrier to interbreeding, thus leading to reproductive isolation. -

Help - a question on new species

chadn737 replied to julianm's topic in Evolution, Morphology and Exobiology

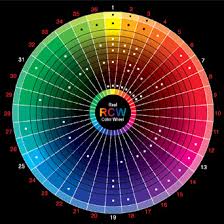

Interbreeding is the standard definition, but it is a very imperfect one. The problem of what is a species is long debated and even has its own name..."the species problem". Here are some papers on the species problem. The concept of species goes back before evolution or genetics. The first person to give a definition for species based on biology was John Ray in his 1686 volume of Historia plantarum generalis. Thats nearly 200 years before Darwin or Mendel. Aristotle's ideas of essentialism still dominated. Like most, if not all classification systems, this is definition is incomplete and somewhat arbitrary. Do you remember when Pluto was declassified as a planet? The cutoff line of what is a planet is somewhat arbitrary. Pluto for one doesn't care whether it is a planet or not, but we humans impose such standards of classifications onto nature because it helps us organize it and so reduce the complexity to something more easily understood. However, we should always keep in mind that these divisions are somewhat arbitrary, because when we begin to think they are actual and represent hard lines of division, then it leads to problems. This sort of essentialist thinking is one of the problems many Creationists have with grasping Evolution. They think that there is some sort of hard line and so often mistakenly believe that there had to be a point where species A became species B. Perhaps a better way to think about it is with a color wheel (see attachment). Now if we compare Blue to yellow....there is obviously a difference. But at what point does green and yellow become distinct? If you look at far enough points on the wheel, they are obviously distinct, but in between there is an area where it really becomes impossible to tell if the color is more green or more yellow. Now if we think about the phylogenetic trees...if we compare the beginning and end of a tree...there is a clear distinction, but inbetween....it becomes almost impossible to tell. Our ability to call something species A and species B depends in no small part on the time in which they have been separated from each other and allowed to accumulate differences. Now there are rare exceptions to this rule. For instance, when two plant species hybridize to form a allopolyploid, that hybrid is essentially a new species in a single generation. -

Domestication in the home

chadn737 replied to For Prose's topic in Evolution, Morphology and Exobiology

Domestication is a clearly an evolutionary process, regardless of what the reasons for it. But discerning the causes for such changes is difficult indeed...unless it be something obvious, like use as food. -

Domestication in the home

chadn737 replied to For Prose's topic in Evolution, Morphology and Exobiology

While pets can have demonstrable effects on human mood, behavior, and even hormone levels....showing that this is an evolved response is quite a difficult matter. Quite frankly it will be near impossible to disentangle it. For instance, one possibility is that such behaviors are a sort of crossover of human behavior towards child care. Meaning, that the evolved behaviors evolved in reality for taking care of children...pets becoming a substitute and essentially hijacking this response. -

I would argue the opposite. The organism is a composite of its genetics. A single allele can be defined very clearly, whereas a species is a very muddled term. We can measure the existence and frequency of an allele in a very straight forward way. This has long been the strength of phylogenetics.

-

The problem here is when do you make a distinction between the ancestor and the descendant population? With some exceptions, the evolution from ancestor to descendant population will occur at such a rate that one generation will always be able to interbreed with the succeeding generation. It is only over great lengths of time and the separation of many generations do reproductive barriers evolve. Any barrier drawn will be arbitrary....you can't set a specific line saying "here is species A" and "here is species B". In this sense then, what goes extinct is not a species, but a pool of genetic variants.

-

Help - a question on new species

chadn737 replied to julianm's topic in Evolution, Morphology and Exobiology

The problem with understanding speciation is that people do not think in terms of "trees" and time. It is quite common during the course of speciation for two populations to interbreed or at least be capable of interbreeding. Even those populations that are obviously distinct "species" may be capable of hybridization and even producing reproductively viable offspring. This is especially common in plants. Take for instance this representation. Think of the circles as individuals or lineages....you can see that as the populations begin to diverge, there is an imperfect separation of different lineages. Early in the divergence of the populations, interbreeding will still be possible, but it will be reduced. With time there will be less and less such mixing, until you reach a point where the two simple stop breeding altogether, even if still capable of such interbreeding. The key to speciation is reproductive isolation. This can occur relatively rapidly...say colonization of an island by a population that is then cutoff from the original population, or it can occur over long periods of time. The true definition of a species, like so many things in Biology, is imperfect, a matter of convenience. Increasingly, I try to dispense with the idea of species in my thinking and instead think in terms of populations. -

For general cultivation, it is routine to make a large batch, put it in a sealable bottle, sterilize it, and use as needed. Yes, over time and with subsequent reheating you will change the composition, but its rarely a big deal for routine use.

-

Assuming that the enzyme in question is a restriction enzyme....that definition doesn't work for other kinds of enzymes.

-

How do you know your ligation is fine? Have you tested a control plasmid?

-

That's a lot of unnecessary gel purifications. I never do gel purification unless I need to separate two large fragments, such as an insert from another vector. Furthermore, T4 ligase generally works best at ~16C spread out over several hours. I also don't see the point of inactivating the ligase, I have never done this. Just transform it without this step. Consider doing a longer digestion as well. 15 mins is pretty short, depending on how much you have in your reaction. There are really a lot of possibilities. Sometimes cloning just doesn't work and you hit your head against the wall and have to start from scratch. I also used to run some of my ligation reaction on a gel alongside the digested vector. If the ligation reaction had a larger product I knew the ligation worked and I always had a successful clone.

-

Why do you think Neanderthals were poorly adapted? They were very well adapted for the environment in which they dominated. Nor did we evolve from Neanderthals. Anatomically modern humans evolved independently in Africa. Admixture between the two populations did occur in parts of Europe and Asia, but we did not evolve directly from them or derive the majority of our genetic variation from them. Evolution has not stopped. I think this misperception commonly arises because many people equivocate between evolution and natural selection. While it is probably true that modern medicine and other advances has removed or lessened certain historical selective pressures, this does not mean that evolution has stopped. As the evolution of a species is the change in its allele frequency, the effect of removing strong selective pressure is to allow the proliferation and accumulation of new genetic variation that was historically would have been eliminated. This leads to altered allele frequencies and even altered phenotypes. More impactful, however, has been the fact that our technological advances has allowed explosive population growth which increases the number of rare variants: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/336/6082/740 http://www.sciencemag.org/content/337/6090/64 http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v493/n7431/full/nature11690.html Colonization of new planets will not stop evolution. In fact, it will most likely lead to the same sort of scenarios that have shaped individual human populations for thousands of years. Most importantly will be the founder effect. The colonization of space will most likely occur, at first, by a small number of select individuals. Even after that, migration between Earth and its colonies would be reduced. Thus the majority of the ancestry of individuals born outside of Earth would be derived from this small starting population. This will have a very immediate effect of creating a population of humans genetically distinguishable from that of Earth. Furthermore, with a smaller starting population, Genetic Drift will play a more prominent role and new/rare mutations could rise in frequency and dominate a population very rapidly, regardless of any effect of fitness, unless the selective pressure is very strong. We have numerous examples of exactly this scenario occurring time and again in the history of human evolution. Perhaps the best studied are the people of Iceland, where nearly the entire population can trace its ancestry back to a handful of founding individuals. The effect being a genetically isolated and distinct population. The oldest anatomically modern human fossils date back ~190,000 years ago.... http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omo_remains

-

The problem I have with the question is that it seems to imply that "genes" are deterministic for behavioral traits. This is simply wrong. Furthermore, Dawkins goes to great length at the start of the book to make it clear that this is not what he is saying.

-

I work on DNA methylation. Variation of methylation in natural populations, trans-generational inheritance of methylation variants (epigenetics), and the interplay of genetic variation and variation in DNA methylation, with long term goals of manipulating these differences.

-

I'm sorry, but the question is stupid. The Selfish Gene is an analogy. This question also completely misunderstands how genetics works. I really don't know how to guide you in this. You would be wrong to say that the genetics of height renders other factors like nutrition irrelevant, so why would genetics render thought irrelevant?

-

Hi, still fairly new to the forums. I am a geneticist with interests in genetics, evolution, molecular biology, plant biology, and agriculture. Spent 8 years in the National Guard as a combat engineer and served in Afghanistan. To a lesser extent I have interests in conservation, ecology, literature, international politics, the military, and history.

-

I didn't criticize you with being divisive (please don't use "divisionary", this is not a word). I grew up as a Creationist. The idea of microevolution has largely been accepted even amongst the most ardent young earth creationists. Ken Ham even stated his acceptance of microevolution in the debate. Presented with such evidence, the Creationist response is that such changes already exist within a population and that they cannot explain the macroevolutionary changes necessary. You must be prepared for this.

-

This is a general problem for all fields. There is nothing special about scientists in this regard.

-

The problem is that many creationists accept microevolution as fact, but insist on a barrier to it. I don't think the problem really lies in proving microevolutionary change, which has been utilized by breeders for centuries through artificial selection. The problem is promoting a proper understanding of phylogenetic relationships and demonstrating that there is no barrier between microevolutionary change and macroevolutionary changes. Hence the importance of teaching "tree thinking".

-

Gould was wrong about a great many things. Amongst other things, he often let his politics shape his science. I can show highly similar traits that evolved similarly. I never stated that evolution produces identical organism, but I do maintain that it will produce identical traits. In Biology this is known as homoplasy and convergent evolution is a long recognized fact. Let take flight for example. Birds fly, but so do bats. They even have similar body plans that allow them to fly. Yet they are obviously not related. Rather, they evolved the same traits under selective pressure. Another example can be found in whales in dolphins, which possess bodies remarkably similar to fish. C4 photosynthesis in plants appears to have evolved multiple times. Rerun the clock and would you get humans? No. Would you get something similar enough to humans that we would recognize the similarities? I don't see why not.

-

I have no idea. I don't think anyone could answer that question given how little we know of the genetics of it. It may very well be that exoskeletons evolve easily, that still does not make it unlikely for vertebrates to evolve. My entire point is that we can't say that evolution doesn't repeat itself.

-

Why isn't it as likely? The point is that the same traits evolve multiple times. Homoplastic traits are surprisingly common. You simply can't make such statements "but a complex trait like a back bone is not as likely" without some reason. What is the evidence that it would not be likely?

-

Far more specialized and complex adaptations have arisen. The fact that vertebrates may have gone extinct at one point does not mean that they would not have evolved again. After all, we see the same traits evolving time and again regardless of their complexity. For instance, social behaviors and altruism are abundant, despite this supposedly being a very complex trait.