-

Posts

2048 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

25

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by Eise

-

No material can have a net negative charge. [Answered: Wrong!]

Eise replied to martillo's topic in Speculations

Hi Martillo, What I do not understand, is that you don't start to read. Several experts here have told you, that electron configuration in atoms and molecules, and chemical bonds, are thoroughly understood, and already belong to established science. Of course, there are still problems enough, but many (most?) of them are practical: even if we have the basic theories, the calculations become next to impossible when many particles are involved, and therefore approximations or experiments are needed. (just imagine: there is still no general analytical solution for the 3-particle problem , i.e. 3 particles that move under simple Newtonian gravity! How more difficult is it when you want to describe multiple particle problems for atomar conditions!) The problem you have seems to me that what you understand about these topics so far, does not fit the concepts you use to approach atomar and molecular processes and configurations. I can only say: believe the experts here, and the established science, that there is no problem. There simply is no need for a new basic theory, so don't spill your time on it. Use your time to get into the present scientific understanding. Read about quantum theory, quantum electrodynamics, and chemical bonding. Try to find the books that fit to your present understanding, and bring you to a higher level of insight about these topics. I am sure that some of the participants in this thread will help you to find the right books (or maybe even good web pages). I assure you, great new vistas will be opened in your mind. Let us know, if you need any help to find the right texts for you. Cheers, Eise -

No material can have a net negative charge. [Answered: Wrong!]

Eise replied to martillo's topic in Speculations

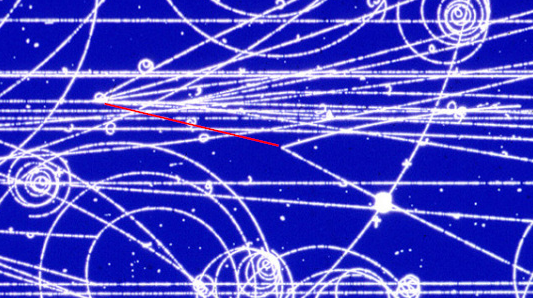

Yes, I know. Here the details of this picture: From here. And really, very relative: Bold by me. In fact, for a bubble chamber liquid hydrogen is less dense than anything else that can be used for a bubble chamber... And in case you wonder why I know your picture so well: I am wearing this T-shirt at the moment: Of course I looked up where the picture was coming from. I was pleasant surprised that the picture was made in my birth year... For you, I drew the path of the neutral Lambda particle in red. -

No material can have a net negative charge. [Answered: Wrong!]

Eise replied to martillo's topic in Speculations

This is wrong. Neutral particles make no visible tracks. The V-formed track somewhere in the middle is a neutral Lambda particle that decays there into two charged particles, that seem to pop up from nowhere. The tracks that seem to go in straight lines are just very fast charged particles, so you do not see that they have also curved paths in the magnetic field. -

No material can have a net negative charge. [Answered: Wrong!]

Eise replied to martillo's topic in Speculations

Y apologize, I was wrong stating atoms are neutral at 0ºK only. As I said after: Sorry for being unclear: it is not just your statement about atoms at 0ºK, it was about your complete position as stated in your OP. -

No material can have a net negative charge. [Answered: Wrong!]

Eise replied to martillo's topic in Speculations

Nope. Triboelectric effect Bold by me. Source? Your position would invalidate all of chemistry, physics, and daily experience (especially at children's parties). This is worse than 'Einstein was wrong'. Only 'the earth is flat' tops you here. -

To strive for fulfillment in togetherness with all other living beings. No. We will never know. Last time I looked Philosophy 1 was still alive and kicking.

-

Oh, but there were already many experiments with electricity: Why do you think we don't see such devices anymore?

-

Well, my fingers are burning to show how wrong you are. But when you do not want to discuss on a discussion forum, I am wondering what you are doing here. Giving arguments is the alpha and omega of philosophy, and the alpha and tau of science (and the tau and the omega of science is experiment and observation).

-

I disagree, physics derived from questioning things just like this, and to just shove aside questions like these in the physics community only shows the lack of answers. If questions to unanswered problems is philosophy then what do we really understand, if every thing just creates another problem that cant be answered. Where I do not quite agree with Bufofrog that philosophy is the trash can for all questions that sciences cannot answer, he definitely has a point. In philosophy, we say that your kind of question contains a category error. Causality can only meaningfully be defined in space and time. E.g. following statements should clarify this: a cause always precedes its effect Two events can only be directly causally related when they are in their immediate vicinity But such propositions only make sense in space and time, they are meaningless when talking about space and time. Causality does not apply to space and time themselves. The relationship between spacetime, energy, and gravity is a conceptual one, not a causal one. By giving the conceptual relationships between these three, one could say that the job of the physicist is done. As a philosopher, of course one can ask all kind of petty questions ('is space really curved?';'What is ontologically first: gravity or time dilation?'). Physicists can do very well without such questions, and their possible answers. Some of these questions can be fascinating (e.g. PBS spacetime has an interesting episode about the latter question). Exactly these kind of questions show that 'causality' does not apply to spacetime itself.

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eise_Eisinga a great-great-<n>-great cousin of mine. A debunker 'avant-la-lettre'.

-

I have the same problem. But I noticed it makes a difference if I am signed in or not. When I am signed in I get at the last posting; when not it jumps to the beginning of the thread.

-

Significance of Philosophy in Science

Eise replied to Jori Gervasio R. Benzon's topic in General Philosophy

No, philosophy can help to increase the quality of discussions about 'what is good', but not to answer the question directly. Where it is true that questions about science do not belong to that science itself, you expect too much from philosophy to provide the answers. The output of philosophy is clarification, digging up hidden assumptions, unmask logical or argumentative fallacies, etc. Depends on what mean with 'mere' in this case. If you mean hypotheses from lay people, then you are right; but such hypotheses aren't philosophical either. But for a scientist, who is working in his field of expertise, hypotheses are the ground for theory building. Scientific theories do not come from nature: they come via the creativity of scientists. But only these theories are accepted, that stand empirical tests. For critical thinking, philosophy builds quite a good basis. That is useful for scientists too. Being aware of societal and moral consequences is also useful. -

Binary numbers--- what does "base-2" mean?

Eise replied to PeterBushMan's topic in Applied Mathematics

'Binary numbers' do not exist, neither do 'decimal numbers'. Numbers exist, but we can use different notations for them. Take the number 153, in decimal notation. This means: (1 x 100) + (5 x 10) + (3 x 1). With exponents you could write it as: (1 x 10²) + (5 x 10¹) + (3 x 10⁰). So the number is expressed as sums of multiples of powers of 10. So the base number is 10. In binary, 153 is written as 10011001, which means: (1 x 2⁷) + (0 x 2⁶) + (0 x 2⁵) +(1 x 2⁴) +(1 x 2³) + (0 x 2²) + (0 x 2¹) +(1 x 2⁰) Which is in decimal: (1 x 128) + (0 x 64) + (0 x 32)+ (1 x 16) + (1 x 8 ) + (0 x 4)+ (0 x 2) + (1 x 1) = 153. Every number can be written in every base. -

By scientists, not by science. But the questions are still philosophical, and a training in philosophy definitely helps. I don't care who does the philosophising, as long as it is 'quality philosophy': well argued positions, well informed about the subject (physics in this case), but also well informed about the philosophical relevant areas to avoid overhauled positions, faulty logic, etc. Most of the present-day well-known academicians doing philosophy of physics have double PhDs, both in physics and in philosophy. To exaggerate a little, Krauss, with no extended education in philosophy, is critisising Aristotle, but none of today's academicians doing philosophy of physics. You can use citations to strengthen your point, by citing experts in the field, i.e. valid arguments from authority. I just wanted to show that Mencken is not such an authority. Depends on the purpose. If it is to ridicule philosophy, then sure, you can use such bonmots. If you want to make valid argumentative points, no, not so much. What is your purpose? But then you equate everybody who thinks he is philosophical with philosophy as it is done in academia. You know physics is bullshit? Just read the crackpot postings here. I cannot help it that there are many specialists here in different sciences that can correct wrong positions, but it seems that I am the only one here who studied philosophy as a main subject. And my time is limited; as you probably noticed, I am not posting very much at the moment. Maybe when I am retired, in a couple of years... Yes, but you should not mistake 'playing philosophy' for 'academic philosophy'. But not today's philosophy. And what was Aristotle doing? language analysis grammar logic biology physics philosophy Isn't it a bit funny, just because everything was called 'philosophy' in those days, that modern physics has taken the place of philosophy in the domain of fundamental questions? Just to add a citation by Sean Carroll:

-

Not quite: 'philosophy' was just the name of every activity that wanted to understand the world. (Was Newton a philosopher? His main work is titled 'Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica'.) It is our understanding of the musings of Aristotle that he was active at disciplines that we now distinguish: during my physics study in the context of the history of physics I learned about his 'laws of falling bodies', during my philosophy study I learned about Aristotle's logic (syllogisms, categories, etc), and I assume he would also appear in the history of biology. There are some overlappings, e.g. Aristotle's concept of causality that is interesting for the history of philosophy and physics alike. It is clear to us nowadays that to make methodologically justified statements about nature, you must study nature, not just sit behind your desk and start thinking. However, if you encounter problems, there may come a point where you have to think about the fundamentals of your methods or other assumptions, like in the early years of quantum physics. And that discussion is not over yet, but has shifted. E.g. the question if String Theory is still science, or just mathematically advanced metaphysics. And what about the Multiverse: proponents of some version of the Multiverse generally affirm that there is no causal connection between the different parallel universes. So the hypotheses about the Multiverse cannot be empirically tested. Is that still science? These are philosophical questions. In modern days, no, not so much. Genady is partially right: To simplify: if the topic is nature, it is physics; if the topic is methods and general assumptions behind physics then it is philosophy. And in this sense there are at least periods in which physics needs philosophy, even if it are physicists themselves who are doing the philosophising. But physics does not need music or sports; physicists might, but they are not special in this respect. There are a few reasons, why you got this impression. First, the irony, or even sarcasm, of one of these was just too much. As a science fan, you could get the impression that you are plainly stupid. (If you remember, I also asked him to tone down. To no avail, as he was even banned.) This made it impossible for you to take his points seriously. AFAIR his point was that the selfunderstanding of science (a philosophical topic!) of many scientists is poor, but you read somehow that he implied that science in general is wrong. But the second point lies clearly with you: your utter ignorance about modern philosophy, just picking a few bonmots (some nearly 100 years old) that fit to your prejudices. Here I have a few others by Mencken: Do you really want to call him in the witness stand? Philosophy is not science. In the natural sciences there is always an arbiter: nature itself. Philosophy is essentially reflecting on our thinking. But as the thinking changes, due to developments in science and society, the reflecting will change as well. Grappling with these assumptions is the scientific methodology, which is a part of philosophy. This is a caricature of philosophy. No doubt that Feynman heard these kind of questions, but the way he talks about them, I assume these were questions by 'would-be philosophers', i.e. fellow students who wanted to spread some 'deepities'. You do not find such questions when you look into the 'philosophy of physics' department. Yes, I notice you are pretty good informed about the contents of modern physics and astronomy. But, as you say you are not well-informed about what philosophy is presently doing. So why all these attacks on a discipline you simply don't know, and just take some bonmots, that support your prejudices? Forgot to add, there are physicists, who are much better aware about philosophy, a small list: Lee Smolin Sean Carroll Carlo Rovelli Albert Einstein From the latter:

-

Well, beecee, I hope you are doing well in your followup crusade against philosophy. I find it interesting that you, Krauss, Degrasse Tyson are heavily critisising philosophy, where it is clear to me that you and your scientific heroes have no idea what is actually done in modern academic philosophy. Don't understand me wrong: I have read several books of Krauss, and these are great in explaining modern physics and astronomy for the lay people; and I extremely like the Degrasse Tyson's work in the public understanding of science. However I also recognise without a shadow of doubt that they are fighting a straw man here: philosophy as it was thousands years ago, or hundred years ago. Should I condemn physics as stupid because Aristotle said that F = mv? 2500 years ago? Or astronomers that thought the cosmos is static and exist just out of the stars we see in the Milky Way, not much more than 100 years ago? Of course not, but that is exactly what you are doing when they, and you, are critisising philosophy: as if philosophy has not progressed in those thousands or most recent 100 years (Russel, anybody?). If you say that philosophy has still no answers to the most fundamental questions it asks since thousands of years, then I can only react that physics and astronomy have not either. True, we know much more, and cosmologists can describe the history of the universe until about 10⁻²³ seconds, but the original question 'where everything comes from' is not answered. Even Krauss does not know the answer. So if you would say, e.g., that philosophy still has not answered the thousands of years old question if we have free will, I would say 'maybe not, but we understand the problem much better'. The same as in cosmology: we understand much more about the origins of the universe, but we do not have the definitive answer. You are using different critera for the progress of science and philosophy. In trying to understand and accept the present scientific difficulties in answering this question, one is, eh... philosophising. Thereby: every science has its philosophical assumptions. See my present disclaimer ('There is no such thing as philosophy-free science; there is only science whose philosophical baggage is taken on board without examination.') Grappling with these assumptions is philosophy (at least of one of its subdisciplines). Doing unfounded assertions about philosophy is just bad philosophy. (Yes, when a scientist reflects about the status of his science, he is doing philosophy, not science.) Feynman shows a nice example of the ambiguity of scientists about philosophy: on one side, he finds it completely useless ("What is 'talking'"), on the other side you have his reaction on the question of what magnetism 'really' is (I think even you have shared the youtube of that interview here in these fora); there he is clearly taken a well argued philosophical stance, i.e. he is philosophising. Recently I have been reading What is real? The unfinished quest for the meaning of quantum physics by Adam Becker (Astrophysicist and philosopher). Its historical description shows clearly how heavily influenced the discussions between the 'quantum pioneers' by philosophical stances, and when it is about quantum fundamentals, it still is. With that it also shows clearly how important history of science and philosophy of science are, even for physicists. E.g. it shows how devastating the 'Copenhagen creed' was for an open discussion on the fundamentals of quantum physics, even so much, that you could forget your career, if you showed interest in fundamental questions (e.g. John Bell, working at CERN, helping in calculations for its accellerator/collider, but 'doing work on fundamentals on Sundays' Bell's theorem belongs to this 'Sunday's work'; he even warned Alain Aspect not to strive for doing entanglement experiments, unless he was tenured, (which he luckily was)). Read this book, maybe you get a bit more respect for philosophy and history of science. You will also see that the author himself is not the only one that has both studied physics and philosophy (often in that chronological order). All less talented than Krauss? In cosmology, sure. In philosophy? Definitely not.

-

"I Vitelli dei Romani sono belli." The meaning depends on which language it is written in: Italian or Latin: Italian: The Romans' calves are beautiful. Latin: Go, Vitellius, at the Roman god's sound of war. Another interesting kind of ambiguity. Same with: "Cane nero magna bella persica!" The black dog eats a nice peach Sing, o Nero, the great Persian wars!

-

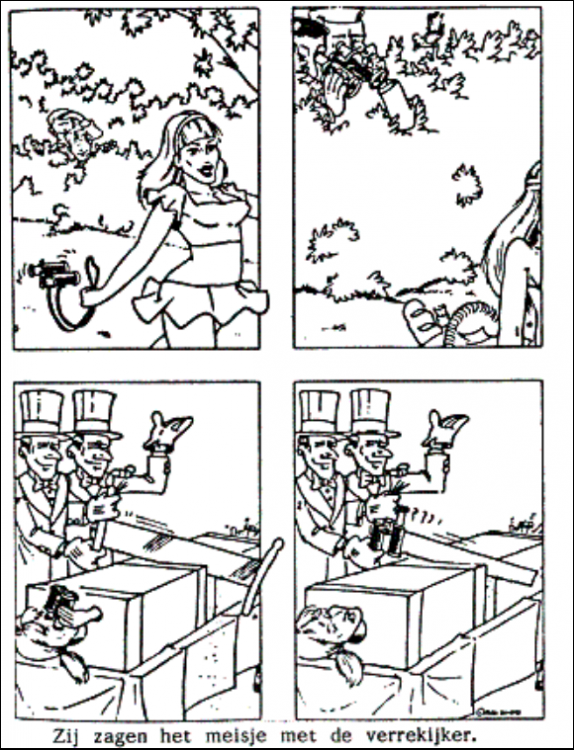

Yep. Funny isn't it? The words are different, but they work semantically exactly the same: "Zagen": present tense of 'to saw', past tense of 'to see' "Met': 'with', with (!) the same ambiguities as in English. You have a talent for Dutch!

-

-

Example I once read about AI in the domain of language understanding. It has 4 (at least?) meanings: "They saw the girl with the binoculars."

-

There have been done several experiments that show that 'experienced time' must not agree with 'real time'. E.g. with brain surgery they have done experiments where the brain area that reacts on touch of the fingers and the fingers themselves were triggered at the same time. Which order would you expect, was reported by the conscious subject? Yes, the tickling of the fingers was reported to have occurred before the tickling of the corresponding brain area.

-

I like that. Just to add: there is also no single time. And to the topic in general: I recently read somewhere this interesting bonmot: the brain is hallucinating constantly, the senses filter out which hallucination fits best for our survival.

-

In 1976 I visited a talk about lasers, for interested laypeople. One of the applications of lasers that were presented was nuclear fusion. I remember the presenter told that in fact the only problem that had to be resolved was to fire the lasers at exactly the right time, to avoid that the pellet would be thrown out of the mid-point of the lasers. That is 46 years ago... Just to add another anecdote to Moontanman's. I think when we had invested all the money in durable energy sources and develop technologies that use less energy, instead of nuclear fusion (including Tokamak and other methods), we would have solved our CO2 emission problems...

-

"About the quadrant. How one should make the hour lines in the quadrants" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quadrant_(instrument)

-

Yes, that is the first problem. So any question or answer on this topic should clarify first which definition of free will one is using. I think measuring free will without treating a human as a subject, but as object only, will never succeed. Compare it with 'meaning'. From the physical properties of ink, it is not possible to derive the meaning of the sentence that it forms. To assess if somebody acted from free will, you need to know her motivations and reasoning. You did not make your definition of free will explicit. What you say here fits to the 'libertarian' definition of free will, or even stronger, a dualistic definition. Something like 'the soul interferes with the physics of the brain'. Same holds for this: I agree that this can be true for certain definitions of free will, as the one you were using above. Personally I think we should adhere to the daily use and experience of free will, but only to an empirical notion of it. Why do people say they did something freely, or just the opposite, were coerced to it? The compatibilist notion of free will comes closest: somebody acts according her free will, if she acts according her own motivations, and not those of somebody else. However, such a definition only works in a deterministic universe. This guarantees that my motivations and actions can be related. Don't throw randomness in it, because then this relation is disturbed. Also, to anticipate the results of your actions, the world better functions in a regular, and therefore predictable way, which can also be guaranteed by determinism. So determinism is a necessary condition that free will can exist; there simply is no contradiction between determinism and having free will. Ah, I know you are joking, but the remark is interesting. It presupposes that a cat can limit your free will. But how can a cat limit something you would not have at all in the first place? I would prefer to say that there are different discourses: you won't find meaning, consciousness, or free will if you only study quarks, electrons, molecules, or whatever. That is because they simply do not exist in that discourse. But they exist in a discourse about choices, beliefs, feelings, ethics, laws, etc etc. The second discourse is not invalidated by the first.