Everything posted by Eise

-

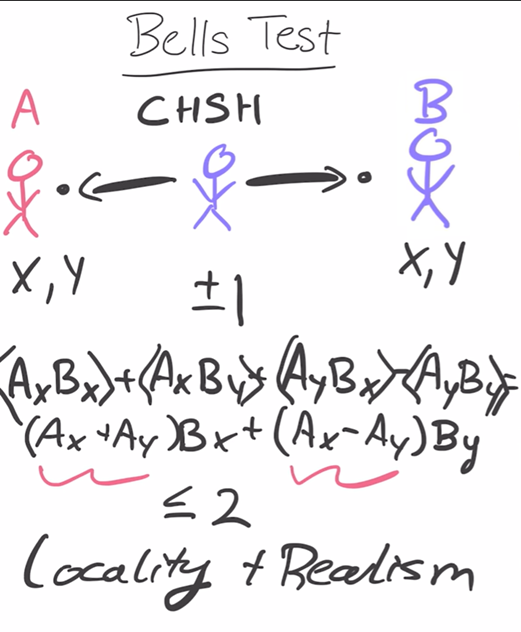

crowded quantum information

WHAT? Swansont showed it: Joigus mentioned it several times. And in Susskind's Quantum Mechanics; the theoretical minimum you find it on page 166. And here you find it on Wikipedia. So refresh your memory: Or show where the formula indicates a signal between the particles. It is called the singlet state, and QM shows it can be created. In that you shifted the meaning away from how it is used in the CHSH inequality. For you, realism includes locality. For CHSH it doesn't. Here you are redefining it: That simply is not what CHSH is about. It clearly distinguishes the two assumptions on which it is based: locality on one side, realism on the other side.

-

crowded quantum information

Wrong as wrong can be. Susskind derives it in his book. She says that only 2 assumptions flow into the CHSH inequality locality and realism. And she says literally: Nope. Not instantly. They even had to ensure that the entangled photons were delayed, so that the conventional signal arrive at Bob first. So quantum teleportation is slower than FTL. Troll.

-

I could not reach Scienceforums for 3 days

Ha! That must be it. Maybe somebody forgot to pay the bill for the address registration? Something like that was my most probable guess. Pity that my networking colleagues didn't think about an ICANN Lookup. Thanks!

-

I could not reach Scienceforums for 3 days

Exactly, that's why I posted it.

-

I could not reach Scienceforums for 3 days

Hi administrators, For 3 days I could not reach these forums. As I see no postings telling us what happened, must I assume it was not a problem at science forums itself? I could not connect from my work, and neither from my home. The error suggested that the URL could not be resolved. Was this a local problem? Swiss? European? Or was it really some problem with the URL registration? I was already desparately trying to find somebody I could contact to find out what was going wrong (WHOIS, trying to find out the email address of one of the moderators). SF is one of my daily mental vitamins. Glad to see y'all back again! Eise PS My, lucky enough very small conspiracy theory module, thought already that it concerned my posting about trackers... PPS At least there seems to be a time gap:

-

quantum determination question

Psst... It is faster than thought...

-

Trackers

Because I have problems with my stone age old Ubuntu, and with that, with the installed browsers, I sometimes have to change from Opera to Firefox. I nearly always use Opera, but using Firefox, with my add-ons, I saw there are quite a few trackers on scienceforums: Is this just in the forum software package, i.e. unremovable? Or is it part of a sponsoring contract? If possible, I of course would like them removed. Otherwise, I assume we have to accept this. I have "do not track" set, but AFAIK it just sends a request not to be tracked, it does not block trackers.

-

crowded quantum information

I think Swansont asked for a QM derivation, not for citations: Which of "not an article about QM" you did not understand? In the hope I correctly understand Swansont's Ansatz, he is doing the following. He gives you the formula which rolls out of the math of QM. I hope you recognise it. Joigus also mentioned it (I think even a few times). The importance of the formula in this context is that it does not contain a dependency of the distance between the measurements, i.e. it is valid even if the measurements are space-like separated. So your task is to show the formula wrong. QM. Just QM. Your citation contains no description of the question 'locality or realism'. I think it also contains nothing Swansont would disagree with. So this article might be a correct description of entanglement, but it is not relevant. The IBM lady you have called as witness, disagrees with you. The video is less than 50 years old... Because, from a classical view, the results are outrageous. Two of the fundamental assumptions of classical physics are challenged, locality and realism (in the technical sense of those words, not of your vague interpretations of them, see CHSH). There obviously were physicists that trusted QM so much, that they did not find it necessary to do such experiments, e.g. Feynman. He was not interested in Clauser's experiment. And Zeilinger's experiments also lead the way to applications of entanglement: quantum cryptography, quantum teleportation and quantum computing. You did read the articles on the Nobel prize website, didn't you? But of course you did not understand them. Hm. Reminds me of a posting here...

-

crowded quantum information

And another foot shot. From the same article: Italics and bold by me. You redefined 'realism', so that it contains 'locality'. But your IBM speaker clearly distinguishes in a very technical way between the two, namely as the only two assumptions of the CHSH inequality. You've made clear for all of us: You cannot understand the argumentative arc of texts And related, you cite pieces of texts that seem to support you viewpoint, but in fact the text as a whole does not You are not able to refer to a modern article (less than 50 years old, if you know what I mean) of a respectable physicist that defends that of the two, locality and realism (in their technical sense, not in your unjustified interpretation of it), we have to give up on locality You do not understand how we use special relativity to argue that there is no direction in the correlation of Alice's and Bob's measurements You do not even understand special relativity And last but not least, you simply do not understand quantum mechanics. I think we should close the thread. Because of Joigus' mental health 😉, and my ability to express my free will (didn't I say I am out?) 😟, and because of this: And I found this elaborate extension of it:

-

crowded quantum information

No need anymore to comment on this. But then, we see how you bend what is said, even in your video. At 7:55 she says that the only two assumptions that went into the CHSH inequality are locality and realism. See the screenshot I made from the video. So it is locality or realism (or both) that we must give up. And to repeat: later on she says "The way that most scientists have interpreted this, is that we have to give up on the idea of realism".

-

crowded quantum information

Fully agree with Joigus. You just showed that you do not understand one single word that MigL, Joigus and I said when considering relativity in such entanglement experiments. And Joigus made such a beautiful drawing, exactly showing what I meant (+1). You are nearing the troll-zone. Instead of sticking to your viewpoint, try to understand what here is said. Please do.

-

crowded quantum information

It is really amusing to see how you shoot yourself in the foot again and again. At about 10:05: It is not garbage, in the end even a lot of physicists thought we have to give up on locality. See my citation of Zeilinger from his Dance of the photons. But his book is from 2010. Now 12 years later, in 'your video', above is said. So it seems the consensus is moving in the other direction. Your counter argument against my relativity however, is garbage, as @joigusalso noted. I did. In my opinion (maybe Swansont, Joigus, and MigL would not agree, that's why I say 'opinion') that in QM, more specifically the wave function, we have reached the limit of our our capacity to know and understand nature. In a Kantian way, one could say that we encountered the limit behind which the thing-in-itself (Ding-an-sich) is hiding. I have a hunge (even more vague than 'opinion'), that there will be no new experiments that will close some of the remaining interpretations (MWI, superdeterminism (of which Sabine Hossenfelder is a fan), counterfactual definiteness). But more Zeilingers will stand up, and will design more unbelievable applications of entanglement. And who knows, some day my hunge and opinion turn out to be wrong? Can you tell us, why you are so attached to the idea of non-locality? Or what you have against loosening our conception of realism? You see, the moon really is there, even if we do not look up. But we cannot observe the wave function. It is only at this very deep level we must loosen our concept of realism, not in our daily life.

-

crowded quantum information

OK, so we assume that in the reference frame of Alice, the source of entangled particles exactly in the middle, and Bob on the other side; nobody is moving against each other. So if Alice and Bob find a correlation between their measurements, it is impossible to say who was first. That is already problematic for you: in which direction is the signal/information/communication/effect/action/interaction going? The situation is exactly symmetrical. Now observer1 flies with great speed from Alice to Bob. He will see that one of them was before the other, and could conclude that one sent a signal to the other. Observer2 flies in the opposite direction, from Bob to Alice, and so concludes exactly the opposite, she will say that the other one was first. If Observer1 and 2 know their relativity, they will recognise that the events are space-like separated, and the correlation must be caused by an event that exists in the respective light cones of Alice and Bob. And lo and behold, there is a one single source of entangled particles in the light cones of both. So the reason of the correlation lies in the past that Alice and Bob share. Like a pair of shoes... There is no signal/information/communication/effect/action/interaction needed to explain this correlation. I have a dejà vu. Another dejà vu... Bell did not do these kind of experiments. I assume you mean Zeilinger. You know, one of the three that got a Nobel prize.

-

crowded quantum information

It seems that you also do not understand special relativity. There is no preferred frame of reference. So in space-like separated events, there will be an observer for whom Alice's measurement occurred before Bob's, and also an observer for whom Bob's measurement was before Alice's. The frames of reference of the source, or of Alice or Bob simply are not preferred frames of reference, because there are none. I thought MigL was very clear about it, and I also brought this point when I referred to this Geneva experiment the first time, but it seems you do not understand it.

-

crowded quantum information

Bell is, pity enough, dead, so he did not get a Nobel prize. You mean Clauser, Aspect, and Zeilinger. And Zeilinger himself says in the book you introduced here in the discussion, that he thinks that of our presuppositions, we have to give up on reality, not on locality. Others, see my list of authors, take an even stronger position. QM is local. And do you realise you really did not answer Swansont's question? You are talking around it, without answering the question. Bullshit. Don't ever say this again. Or better show us where Joigus and Swansont are not uptodate, and you are. Addition: For what it is worth, the publication years of the sources of my 'authority list': Coleman:1994 Kracklauer: 2002 Zeilinger: 2010 Susskind: 2015 Gell-Man: 2016 Hossenfelder: 2020

-

crowded quantum information

But nothing on Bob's side shows him that the particle has an entangled partner. OK, if you really need reading help, I am not such a bad guy. - - - - - - Nearly all physicists agree that the experiments have shown that either locality or realism, or both, must be given up. Most physicists think that we must give up on locality. That is exactly what Einstein meant, and called 'spooky'. It seems weird that when one measures one particle, it immediately influences the other one. - - - - - - But take care! In the next paragraph, Zeilinger speaks for himself, not for 'most physicists'. And there he clearly says, that he thinks we should drop realism, not locality.

-

crowded quantum information

Wrong again: The no-clone theorem and the no-communication theorem are two different results derived from QM. Nope. Yes, he says that local realism is violated, but as MigL already said (and Joigus, and Zeilinger) that means that either: locality is violated, or realism is violated, or both of course. Zeilinger tends to giving up on realism. That's it. I won't react on all your other concept- and word bending misinterpretations. Learn reading, and then QM. I forgot this one: What you are really doing is picking citations, that confirm your pre-existing belief, out of context without understanding the overall argumentation.

-

crowded quantum information

Sorry, @bangstrom, but now you crossed the border of an honest, argumentative discourse. I assume you have some ideological reasons, and that your ideology needs non-locality. Otherwise I cannot explain the huge misses you make here, and your derogation of Joigus' and Swansonts knowledge of QM. The no-communication theorem is derived from the formalism of QM, and is valid on all levels. If you observe something only one time, you cannot conclude that it has changed. In Bell-like experiments, Bob from his side does not notice anything special. He just gets random results, as if he is just doing experiments on some simple particle source. Only when Alice and Bob compare their lists (these cannot be send FTL), they notice that the correlations are stronger than any classical system allows. On the contrary. The problem is you do not understand modern QM. Einstein objected against the non-local 'odour' of QM, but since then, physicists have developed QM further, and e.g. came up with the no-communication theorem, which excludes any FTL communication (and effect, and influence, and ...). Invalidated? On the contrary, the conclusion of the article that seemed contradictory to relativity, was confirmed by Bell-like experiments: the QM depiction of the world that Einstein thought was too absurd to be true, turns out to be true. And still Zeilinger would rather give up realism than locality. That is clear if you would really read his book, understand his argumentation, instead of citing passages from his book that seem to support your position. Nope. Read, and understand what Zeilinger is saying: in short, if Alice does here measurement before or after Bob did, it describes two different experiments, which means different boundary conditions. As said before, of the five ways Zeilinger mentions that could explain Bell-like experiments, Zeilinger dismisses 'back in time propagation', instead refers, to the fact that they are different experiments. Maybe this has a connection, or is even an example of 'contextuality' as meant in the Kochen-Specker theorem? @joigus: do you think that is correct? So no outrage about the position of Gell-Mann, Susskind, Kracklauer, Sidney Coleman, etc.? In short, you are not able to show an authoritative text, that pleads for giving up locality instead of realism. Sigh... Using 'action' again. 'My experts' disagree with you, and Zeilinger explicitly prefers to give up on realism, instead of locality. I am afraid, you forgot again, that teleportation needs an additional classical communication channel. I think I am done here. Unless a Bell-Kochen-Specker-Bangstrom inequality is derived that can distinguish if we must abandon locality, and not realism, (and empirically tested of course), I rest my case. Your ideological glasses make you blind, blind as two perpendicular oriented polarisators behind each other.

-

crowded quantum information

You should better take care of your words, which is very important in such fundamental questions. I made them italic: action: we had this again and again. There is no action, no interaction, no causal relationship, no information transfer, no affect, no influence between the measurements. These are all excluded by the no-communication theorem. change: there is no change, in the first place because a change needs a cause, and that is already done away with with the previous point. In the second place, we cannot detect this change, because we cannot observe the wave function itself. We cannot look deeper then individual quantum measurements, and therefore we can only detect correlations. This is hubris. Swansont knows more about QM than you, me, and Joigus together. You are referring to the mainstream again. And still, you are not able to mention any QM expert precisely arguing why it is that we have to give up locality in QM. Again you do not understand quite what Zeilinger is saying here, and his viewpoint later in the chapter. I italicized the words. Zeilinger does not talk about events 'influencing' events in the past. He is saying that our interpretation of the experiment is different. Alice's measurement occurring before Bob's measurements, or after his measurements are different experiments, i.e. we need different interpretations of the experimental situation. Emphasis by me. And then: And then, more specific: Italics by me. The obvious problem for you is that Zeilinger is a nice and reasonable fellow. So he presents different viewpoints and mentions a few arguments pro and contra these viewpoints. And then you pick out the arguments that fit to your viewpoint. But giving his own viewpoint Zeilinger is very clear: on QM level, we have to depart from realism; not locality. I showed you above that this is not his opinion. And you are using 'action' again! Underlined it for you. Sure, he does not say this is excluded, but that giving our present insights it is not the best solution, because it would mean a total rewriting our present understanding. It is also, clear from the context in which he discusses this, taking the options 4 and 5 behind the sentence: Meaning 'to be honest, there are two other interpretations, but I do not take them seriously'. You really have a problem understanding texts.

-

crowded quantum information

With a single particle, entanglement of course plays no role at all. Which is what Zeilinger says: But Zeilinger uses it in his argumentation for his view. Look how he is doing it: Zeilinger discusses 5 ways out after the confirmation that QM violates the Bell inequalities. Deny realism Deny locality Deny counterfactual definiteness Accept superdeterminism Accept actions to the past He more or less discards 3 4, and 5 rather briskly. Of locality, as already cited early, he remarks that most physicists think that we should give up on locality. However he tends to give up on realism, because this seems to be the conclusion of the Kochen-Specker theorem, and its first empirical tests. So the KS theorem has directly nothing to do with Bell states. But for Zeilinger it is a hint that of 'local realism' (which, as Joigus explained means 'locality' and 'realism' taken together), we have to loosen our concept of a reality behind our quantum measurements. Please reread the chapter 'What could that mean?'. (Warning: he does not discuss these in the exact order as I did here. I streamlined his argument here. First he mentions the first three assumptions, then he argues against (3), then he discusses locality and realism, and only then he mentions superdeterminism, retro-temporal causation, just to discard them immediately.) @joigus: as you see, Zeilinger argues against superdeterminism. He treats it as a kind of 'last straw'. This is his argument: For completeness the 5th:

-

crowded quantum information

Hi Studiot! Does that mean the left and right side of the brain are entangled? Ok, back to business: I found a pdf of Zeilinger's book. This is the paragraph immediately after the paragraph @bangstromcited:

-

The Official JOKES SECTION :)

-

crowded quantum information

This is not fair. You should have included the next paragraph, where Zeilinger gives his own viewpoint. It fits pretty well to @joigus post. Pity enough I only have the the original German version, and translating from one foreign language to another one is a bit difficult. But in my summary: he carefully proposes that letting go realism is the better solution, and refers to the Kochen-Specker theorem, which leads to a similar solution, even without entanglement. Maybe you could cite this paragraph here too? Until now I could not find the text somewhere on the internet. So now, I can add Zeilinger to my list, but only half-half, because he does not express himself as strong as the others on the list. But his tendency is clear.

-

crowded quantum information

Yep, exactly what I wanted to show here: Sabine H says it very clearly: The correlations are greater than those allowed by a deterministic, local theory, not by quantum mechanics. So in QM the correlations are local. Sorry, the error is yours. Your interpretation is wrong. Compare with all citations @joigus made from the video, in which words like 'seems', 'appears', 'says' are heavily used. And in the sentences you cited, she sets the records straight. In QM there are no non-local causes/signals/information transfer/affects. I even just discovered that for my point 1 (of the three points above) has an official name: the no-communication theorem: My italics. So what is left? Correlation. And correlation can be faster than light even classically: that is the example of the left and right hand shoes. Condition is that the correlated 'events': opening the boxes; measuring spins, have a common history. And that they both have. Putting the two shoes in the boxes; creating two entangled particles. The only astonishing is that the correlation in QM is stronger than in classical mechanics. That definitely has a 'FTL odour'. But 'odour' is just as a physical concept as 'spooky', namely none. Coin flips can be explained classically. QM correlations cannot. And further I am still waiting of citations of authoritative QM experts that say that in QM there is 'spooky xxx' at a distance. So no simple text books, these are already critisised by Sidney Coleman. So reference to authorities, please. And of course no popular science books.

-

crowded quantum information

Hurray! Clauser, Aspect and Zeilinger got this year's Nobel prize!😃 Now the newspapers will be full of articles saying that they have proved non-locality with their experiments.🤪