-

Posts

2038 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

24

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by Eise

-

It is also difficult to explain what I don't see, if I don't see it... However, I see something else: Time is implicit in 'running'. I keep thinking about those math video's where they animate this 'running': A point is moving along the x-axis, and on the y-axis a point moves according to f(x). And in my opinion, that is the point where also the word 'change' can be used. We change the values of x, and show how the value of y changes. So time is implicit when we say 'y changes according to the changes of x'.

-

Is there such a Thing as Good Philosophy vs Bad Philosophy?

Eise replied to joigus's topic in General Philosophy

That would be the death of most sciences. As an antidote to such ideas I recommend to read Feyerabend, Against Method. And equating methodology and metaphysics seems also wrong to me. Compare: methodological and metaphysical naturalism (the only source of knowledge is nature vs. there are no supernatural phenomena) methodological and metaphysical behaviourism (the only way to study people's minds is by observing their behaviour vs. there are no minds, only behaviour) That excludes mathematics, astronomy, history, literature, just to name a few. I highlighted the important words for you: So, no, what you wrote above is not a possible correct interpretation of Genesis 2:9. Maybe something like the red and blue pills... What axioms? Philosophy is trying to understand thinking. In the first place how we actually think (depends of course a lot about what we are thinking: natural sciences, politics, 'Geisteswissenschaften', ethics etc). Then how we should think, to come to valid conclusions. And then how we should think to live a good life. Your view on philosophy is a bit one-sided. I highly doubt that. But to find out, one should ... guess what. -

Is there such a Thing as Good Philosophy vs Bad Philosophy?

Eise replied to joigus's topic in General Philosophy

New International Version, Genesis 2:9: -

I am afraid I really do not see the crux.

-

Somehow I think you exactly make my point. No dynamics, therefore no change.

-

I tend to disagree. In a graph without time, you would say that to every x belongs a value f(x). So e.g. for x = 2, f(x) = 4, for x = 3 it is 9 etc. That is a 'static' view. You can also ask for the derivative, e.g. for x= 2 f'(x) = 4, for x = 3, f'(x) = 6 etc. But that is again a static view. Only in a 'dynamic view', where you continuously change x and see how f(x) changes dependent on x, your point becomes valid. But with that, we have introduced time, namely on the x-axis. In my opinion you are using metaphorical speech. Imagining how we 'run' through the values of x, we see how f(x) varies.

-

Is there such a Thing as Good Philosophy vs Bad Philosophy?

Eise replied to joigus's topic in General Philosophy

My interpretation of the paradise story contains a certain wisdom: 'knowing' the difference between right and wrong, good and evil, led to the banishment of Adam and Eve from paradise. What is 'bad science'? E.g the development of nuclear fission: it gave us nuclear energy and an arms race. Or is 'bad science' science that is methodologically unsound? If the latter, then bad philosophy would be that you stop with an honest investigation when you do not like the result of your reasoning. -

The bible was written by people, based on hear-say, a lot of fantasy, some wisdom, and looking at the old testament, a lot of revenge. A book saying 'all in this book is true' doesn't make it true. First, what makes you sure the story is not fantasy? Second, what is more probable: A Jewish tribe of a few 100 people escaped from Egypt, passed the Red Sea during low tide, and soldiers of the pharaoh following a few hours distance, when it was high tide, and gave up. And then the story got more and more exaggerated. A god split the Red Sea in ways that are physically impossible And special for you: how did God this, giving the limits she set himself (classical physics), using only the 'wiggle room' given by QM Direct evidence would be that we somehow observe God is doing it. And I also have no idea why, when science has no explanation for something, it would be exactly the Christian god. "It is in the bible" doesn't do the job. To give an example: we are pretty sure dark matter exists. But we still have no direct evidence: we only see its gravitational effects. Or take gravitational waves, before they were directly measured by LIGO: there was indirect evidence from binary stars, loosing rotation energy.

-

You mean this? The Tale Of A 1986 Experiment That Proved Einstein Wrong That is not true. Both QM and relativity are tested thoroughly. So if there is a new theory, it should at least explain what we already know to be correct, i.e. it should be consistent with all experiments we already did (e.g. the quantum eraser experiment). And I do not think you find new theories more intuitive than QM: string theory (10 dimensions, very intuitive), quantum loop gravity (time and space are not fundamental, also a very intuitive idea), to name just two.

-

Is there such a Thing as Good Philosophy vs Bad Philosophy?

Eise replied to joigus's topic in General Philosophy

Wondering what definition you are using. Make a comparison with science: would you only accept science that gives the answers you like? Keeping a viewpoint fixed is the end of philosophy. Any honest investigation can lead to results you do not like. But faking truths might be worse in the end. Take the idea of God, who gives people a purpose and the right rules of conduct for people to be happy. Wouldn't that lead to the highest possible good? So we keep that fixed and do not discuss this? Is that philosophy? Or dogma? -

Repeating that QM does not explain quantum erasure experiments does not make it true. If this were a theory, then you must be able to point to this entity you call 'God'. E.g. pray to Her that all photons of a standard interference pattern arrive at just one place, and then when this happens you have a point. (or you could do a human sacrifice to the Devil, and ask him to do it for you...). I don't hold my breath... You are right: if you engage in relativity and QM you will get an intuitive understanding of them in the end. For relativity AFAIK mathematical consistency is proven. (Maybe some real physicist can chime in here). Really? I think you have found propositions of relativity that are against your intuitions. A few points about special relativity: it is experimentally tested to the bone: Tests of special relativity It functions as a physical metatheory. Every fundamental law of physics must be formulated in a way that it is Lorenz-Invariant. If you apply this requirement to electrical fields only, magnetism automatically rolls out. Early QM (Schrödinger equation) was not Lorenz-Invariant. Dirac reformulated it, and out rolled spin and anti-matter, which both were experimentally proven to exist Some daily phenomena can only be explained by taking special relativity into account, e.g. the liquidness of mercury, or the colour of gold. Do you want to understand relativity and QM, or do you want to live further in the illusion that you understand them (and therefore... God!). For the latter you do not need me anymore. I've said enough.

-

But everybody has different kinds of intuitions! How can this be a criterion? On the other side, people who work constantly in the area of quantum mechanics, may very well develop quantum intuitions. This is always the case: when your are journeying through well known terrain, you can do this intuitively. And why would these models not be correct? Based on their understanding of QM, physicists derived that it would be possible to design a quantum eraser. They did the experiment, and it worked as QM predicted. So how can you conclude from the quantum eraser experiment that QM is not correct, when it correctly predicts what happens? One of my favourites (just about one minute):

-

Is there such a Thing as Good Philosophy vs Bad Philosophy?

Eise replied to joigus's topic in General Philosophy

No posting of mine was ever moved to speculations or trash. And as of this writing, I am not banned... And if you think you base your life on facts only you are deceiving yourself. -

Which is another good point. God's interactions would only show in quantum physics? And it reduces his impact to a the little 'wiggle room' quantum physics allows? For the rest God must play according the laws of physics. And even if such interactions would be necessary, how could you identify them arising from the Christian God? Why not demons, the devil, Zeus, Allah, Brahman or the flying spaghetti monster?

-

Is there such a Thing as Good Philosophy vs Bad Philosophy?

Eise replied to joigus's topic in General Philosophy

Forgot this: pragmatism is a philosophical viewpoint. -

The relationship between the mind and the observed world.

Eise replied to geordief's topic in General Philosophy

I think there might be an easy way to understand why qualia do not help a bit to understand consciousness. Take the example of the 'upside down' goggles. In experiments, people got used to them after about a week. These people function perfectly in daily life, even not being aware that everything was turned upside down. Until they take of their glasses! Then again they experience the world upside down, and they again need some time to get used to it. Now ask them: are they used to their upside down quale, or did their quale turned upside down? Is this question answerable? And if it is not, what use is the concept of qualia? Qualia are scientifically inaccessible (per definition!), and philosophically useless. Why add some concept to the concepts we already have, like consciousness, or observation? My (and I think also Dennett's) view in the case of the upside down glasses, is that we simply get used to the 'upside down world'. After some time, we can act as before based on our (upside down?) world. In neurological terms, the neural pathways somewhere between eyes and our motoric system have changed. But that 'somewhere' is essentially vague. There is no central control in our brain where all observations come together, and from where our motoric 'commands' are initiated. So the question, is the picture in central control turned upside down, or are our commands turned upside down (the command take your arm up is changed in take your arm down) makes no sense. Qualia would be what we see on the screen, but such a screen does not exist. To be honest, I am not aware of any qualia: I am aware of things around me, that my stomach hurts (or better, that I feel pain in my belly), etc. There simply is no way to 'access qualia'. Which means they are just theoretical constructs. And I agree with Dennett that they leave a track of stupid philosophical problems. The concept of qualia should go the same way as phlogiston, or Aristotle's concept of impetus (the agent that forces objects to move). Do not forget, Dennett explains consciousness (of course one can discuss if his explanation is correct): what he definitely does not is explaining it away, as many critics accuse him of. And where Dennett expresses himself on topics of ethics and politics, he is highly humanistic in his views. He definitely is not an 'eliminative materialist'. On a personal note, I see Dennett as one of those philosophers that helps me on my Zen-path: to see through the illusion of an independently existing 'I'. Meditation is the direct experiential way to realise it; philosophies like Dennet's are the intellectual companions on that way: not essential for the way, but a nice help for intellectually inclined people. (But do not take the boat with you when you crossed the river with it...) -

Is there such a Thing as Good Philosophy vs Bad Philosophy?

Eise replied to joigus's topic in General Philosophy

Now that is an example of bad philosophy... And a pretty good example of my present disclaimer: With other words: what you say is a philosophical remark. E.g. it is based on the assumption that only empirical facts matter in life. But that itself is not an empirically verified position, so, according to you, it distracts from true knowledge. Your position is self-refuting. As to the question of the poll: of course there is good and bad philosophy. But we should keep Strange's distinction in mind: 'philosophy' as a 'philosophical theory', i.e. the contents of what a philosopher is saying about the subject at hand; and 'philosophy' as an activity. Which of course agrees more or less with the same distinction in science. Good philosophy, in modern times: Is well informed about relevant science, culture and politics Takes into account other viewpoints about the topic at hand Confirms or refutes other viewpoints with good arguments, i.e. arguments that are relevant and well supported by sciences and other well argued philosophical viewpoints Is extremely aware of the methods it uses to argue for a certain position. Bad philosophy: Only expresses opinions without arguing Uses arguments that are already refuted by others Confuses scientific speculations with philosophy The specialty with philosophy which distinguishes it from sciences is that in science the domain of knowledge it tries to gather differs from the (transcendental...) subject (i.e the one that observes, experiments, and expresses ideas about the object) of the domain. A physicist investigating certain phenomena does not investigate herself. As I said elsewhere here, the object of physics is not physics: it is the natural world as we observe it. As soon as physicists investigate physics, they are philosophising. Philosophy is essential reflective: it tries to understand our thinking with thinking, just as the physicist thinking about physics. -

Yes, there is. The explanation follows from quantum theory. Your position is even worse than 'Science has no explanation, therefore God'. Your position is 'I do not understand, therefore God'. I was very clear about QED: quantum particles take every possible route. This is intuitively not understandable. But the math of QED is very clear, and experimentally tested to the bone. So citing myself: So I could amend my remarks above a little: because you cannot imagine how this works, God exists. There are now several options for you: Delve deeper into quantum theory, so you can see that even the weirdest experiments done, like the quantum eraser, follow from quantum theory. It is a difficult way, of course, but the vistas you get when you start understanding quantum theory are fantastic. If the math is too difficult for you (which is nothing to be ashamed of, it really is not that easy), trust the people here that do understand quantum physics, that there really is nothing unexplainable even in these weird experiments. Or keep following your present thought model: for everything you do not understand, assume 'God did it'. A nice corrolarium of point 3 of course is that the less you understand, the more room there is for God. So, what way will you follow?

-

Do you think that the quantum-erase experiment just happened accidentally? Playing around with light in tubes and half-mirrors etc? No, it follows from QM. However, this conclusion is so against all our daily intuitions, that of course they wanted to test if that really happens. So they did the experiment, and lo and behold! another empirical confirmation for QM! And having a theory from which the facts follow is also called an explanation for these facts. The problem with QM is not that we do not understand our quantum-mechanical experiments. It is the impossibility to make a picture of what is happening in terms of our daily experiences (where e.g. something can be a particle or a wave, but not both) that makes QM such a strange theory. And I already told you what QED has to say about 'which way': a quantum particle is taking every possible way, but we observe a phenomenon only there where we have constructive difference. You cannot imagine a photon taking every possible way? Then read the previous paragraph again. Or read Feynman's book about QED, as Strange already suggested.

-

In QED photons (or any other quantum particle) take all possible paths, including the paths through the two holes. However, due to destructive interference the effect cancels out nearly everywhere, except on the place where there is constructive interference, i.e. there where we see the interference pattern. No need for Somebody to control where photons can arrive. QED is one of the best empirically proven theories in physics.

-

The relationship between the mind and the observed world.

Eise replied to geordief's topic in General Philosophy

This is difficult to answer in its generality. I tried to give a hint with my expression of 'consistent correlation': everytime we see A we also see B. And we see B only when A also occurs. If that is the case, i.e. a 100% correlation, we must assume that somehow causality is at work. Of course it can still be that C causes first A and then B, so there is no direct causal relationship, that would be 'causality around one corner'. In less than 'consistent correlation', it can be just by chance, or there are many possible causes involved in the happening of B (maybe B can even occur without A occurring). I think we can only be sure that if A causes B, then A and B are 100% correlated. But not the other way round. But I must add that both defining causality, and recognising it, are very difficult to analyse. First of course is a philosophical task, second a scientific one. Ow... qualia are a highly disputed concept in philosophy. In short, I would say 'qualia' is just another word for experience. Maybe you want to read this article of Daniel Dennet: A History of Qualia (pdf): -

The relationship between the mind and the observed world.

Eise replied to geordief's topic in General Philosophy

Hmm. Gravity has all attributes of a causal agent, even in a Newtonian view. Think about a contrafactual analysis of gravity, e.g. "Without the sun being there, earth would travel in a straight line". And 'correlation' is a more vague concept than 'causality'. Mostly, when there is a consistent correlation between 2 phenomena, there is some causality hidden there, maybe around 2 or more corners. But of course, the instantaneous action is a problem, especially for us, who know c is the maximum speed that causality can have. However, I think in a Newtonian framework, the instantaneity is not a problem. Non-locality however is, and Newton saw the problem, therefore his 'hypotheses non fingo' concerning the 'action at a distance'. My, possibly naive, answer to this as follows: we only can recognise causality where we see regularities. (Hume would be proud of me...) And every regularity can be described mathematically. (At least that feels right to me. If it really is, I am not sure. Can somebody give an example of a real regularity (not some fantasy science fiction scenario) that cannot be described mathematically?) Formally you are right, but it seems too far-fetched for me. It is my conviction that our consciousness arises in complex structures, and it seems very difficult to build such structures with light or gravity alone. If this is right, a conscious entity must be implemented in a complex structure, and that suggests it must have a physical size which is comparable to ours. If these speculations are correct, the the answer is 'yes'. Dōgen -

The relationship between the mind and the observed world.

Eise replied to geordief's topic in General Philosophy

Maybe I should have been clearer that my reaction was more to geordief than to you. Right. That's why Kant should arise from his grave, to write the third edition of the Critique of Pure Reason, based on all we know now in QM and RT. In his time everybody was impressed by the Newtonian framework, so Kant as well. On the other side, he found Hume's position about the basis of empirical knowledge too weak. If e.g. observing causal relationships were just 'habit and custom', why did Newtonian mechanics work so well? An important difference between Newtonian mechanics on one side, and QM and RT on the other, is that Newtonian mechanics is about objects and processes that are normally observable in daily life, and they all (seem to) exist in space and time and both are seen as a fixed framework. -

'Anti-realism'? Not quite. Kant is a 'grand synthesis' of empiricism (all knowledge comes through the senses') and rationalism (the only way to understand reality is by reason).

-

The relationship between the mind and the observed world.

Eise replied to geordief's topic in General Philosophy

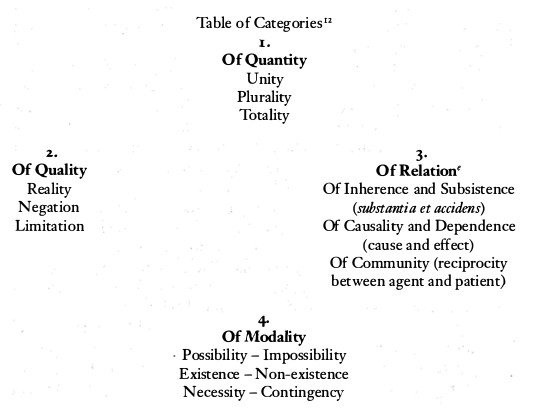

As I said earlier, I am not an expert in the discipline of philosophy, and I haven’t read Kant yet - however, I do speak fluent German, so what this term (which translates roughly as ‘thing-in-itself’) refers to would be external reality before it undergoes processing by the sensory apparatus and the mind. So it is meant to be that which exists independently of any perceptual process, the true essence of reality, unsullied by mental constructs, so to speak. Exactly. Personally, I think the wording 'Ding-an-sich' is not very apt, because it suggests there are more 'things'. I would prefer 'the-world-in-itself' ('die Welt-an-sich'). I like to picture it as an amorphous totality surrounding us. What we observe, the appearances, we observe in space and time. But you should still imagine this as some chaotic stuff, like a Jackson Pollock painting, or the white noise (I think it is called 'static' in English) of an old fashioned TV screen that is not tuned to a TV station. Only when the subject applies the Categories (in Kant's technical meaning), we are able to distinguish things, processes etc. To give you an impression, these are the categories: So there is not 'chair-in-itself'. Only when we apply the categories we get a world with recognisable things, and we can start discussing if a thing is a chair or not. @Markus Hanke: would you read in English or German? I think it is very difficult to translate Kant to any language. But to discuss Kant here you would need the English translation. One warning especially for Americans: it is my experience that even the best American philosophers do not understand a very important aspect of Kant's 'Critique'. The 'Forms of Intuition' ('Anschauungsformen') space and time, and the Categories are not psychological, i.e. not aspects of the individual mind, but are basic conditions that knowledge is possible at all. So they do not belong to 'real existing' subjects, but to what Kant calls the 'Transcendental Subject': the (fictional) subject of all possible knowledge. I think it is the empirical background of Anglosaxon philosophy that makes it difficult to appreciate this idea. Kant's question is not how we know things, but how knowledge is possible at all, split up to different 'sciences': mathematics, empirical sciences, and metaphysics. (The latter is not, according to Kant: it is Reason freewheeling without input.)