Everything posted by Ken Fabian

-

Geoengineering

Any reflectors in space will need to have station keeping capability, ie have the means to move around ie be little (or very big) spaceships. Because any inert material will be pushed out of position (presumably Lagrange zone between Sun and Earth) by sunlight and solar wind. I don't think we could build up low emissions space launch capability even if there were funds for it - and is this to be an alternative to cutting emissions? Dumping dust in the atmosphere is just a thought bubble, not any kind of real option. It offers no alternative to shifting away from fossil fuels to clean energy - an approach which is already gaining momentum. Most leading climate research groups have doubling of CO2 making between 2 and 6C. The doubling depends on what we do, within discussion where action and inaction are inverted; we are acting to emit huge amounts of CO2, many times more than all other kinds of waste. I don't think we will die from methane - there isn't that much of it - but big releases would probably be a part of getting to 6C. As for what happens with 6C of warming? That is a world I find hard to contemplate - I live somewhere where summers can already get unbearably hot and drought and catastrophic fires are showing signs of increased intensity already, at 1C. If economies and societies are so fragile that a transition to zero emissions is fiercely opposed then how much more fragile with the 6C that unconstrained fossil fuel burning will bring? Which over land here could be 8C rise in local air temperatures; I think heatwaves would kill crops and livestock and remnant ecosystems. How do you feel about refugees? But the capacity humans have for making bad situations a lot, lot worse - good governance seems even more essential than ever. And if we cannot manage that now, how much harder in a world changed out of recognition.

-

Inexpensive, fast charging, long lasting EV battery

https://techxplore.com/news/2021-01-inexpensive-battery-rapidly-electric-vehicles.html Battery R&D is a huge deal now - and appears to be making significant progress. Of course commercial ie real world success is still to be shown, but - 400km vehicle range in a 10 minute charge, costs not known but claimed to be lower cost than existing Li-Ion - no cobalt or other expensive metals - and expected working life of >3 million km (2 million miles). Supposed to be because the (lithium iron sulphate) battery heats up to best temperature (60 C/140F) for charging and discharging. I have to say I had always thought raised temperatures was a problem for batteries, rather than a benefit - for most battery types. Some high temp batteries are out there but they aren't like anything I expect for powering our cars or homes. Fast charging is useful but I think for most users most of the time, not necessary. Not the biggest deal in my view. My own thinking is electricity network operators will benefit from EV's being plugged in whenever parked somewhere, to vary charging rates as the balance point between demand and supply shifts, and have access to (an agreed portion of) that battery capacity. For commercial vehicles - road freight - this could be very significant. I'd been thinking trucks might need quick replacement battery packs to avoid time at chargers, but batteries like this could make that unnecessary. I do think just on durability alone this would be significant (if it makes commercial production) - and not only for EV's. For EV's the usual car body, suspension, seats and trim would not last anything close to 3 million km - although improved durability would be a good thing. How that would work for a household with solar on roof interests me - the batteries we have (a different kind of Lithium Iron Phosphate) are expected to last about 15 years... batteries that will go 50 years? At large scale for grids that will be a huge factor for reducing lifetime costs.

-

Tech Giants Shutting Down Violent Social Media Cesspools

Am I correct in interpreting the US prohibition on Congress restricting the rights of a free press as affirming the right of media proprietors to express partisan political views and use their papers to promote them? That seems to include the right to NOT promote views they disagree with and even allowing publishing of falsehoods - with not very compensatory right (if you can afford it) to seek legal redress for slander. It is difficult for me to interpret the deplatforming by social media companies as different to a newpaper editor choosing promote some kinds and to leave out some kinds of content, or to refusing to publish letters to editor.

-

Is global average temperature a useful or thermodynamically valid concept?

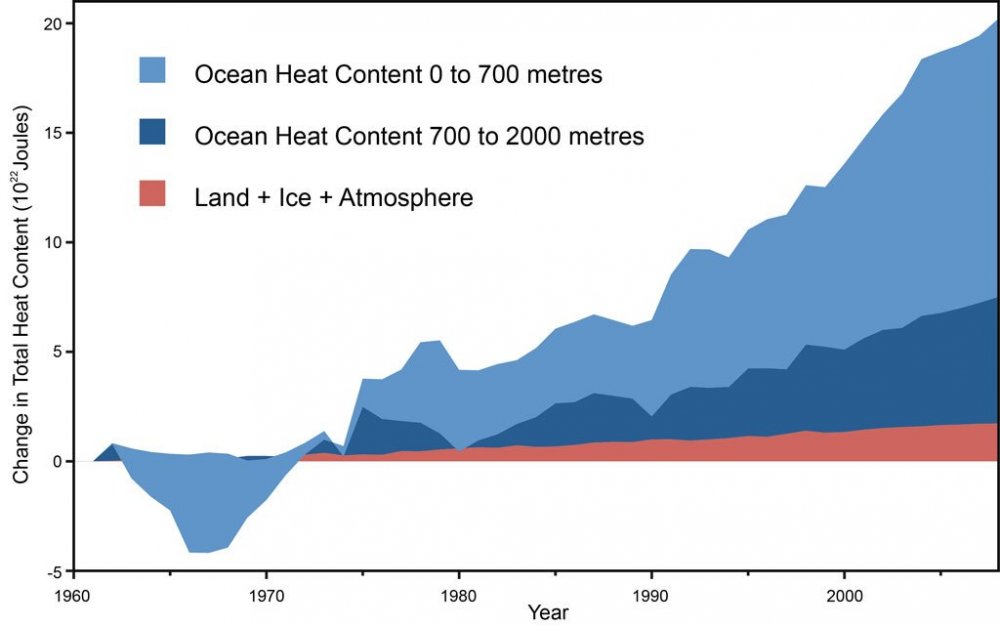

It goes both ways - I think more a case of sea surface temperatures determining air temperature than the other way around. My answer is/was that global average temperature was and is an arbitrary choice for providing a simple, single indicator of change to the climate system; others might do as well or better (I would nominate Ocean Heat Content but the record doesn't go back so far), but weather records are our longest running direct measurements from which change can be observed. So, addressing part 1 of original question, yes it is useful. Is it a thermodynamically valid concept? I think that is probably a pointless question - temperatures are not the same as heat but when they are going up it clearly indicates gain of heat. How closely that temperature reflects overall change to the global energy balance? My understanding is... reasonably well. The extent and nature of local and regional change is a whole lot more complex. The implied question of whether an average temperature is a valid concept - ie the use of averaging samples from some or many places in place of measuring every place - seems to rest on the proposition that the places not sampled could have temperatures and trends of temperatures very different from those of the places sampled. In conspiracy theory argument, chosen for showing the trend wanted. In reality pretty much every place sampled around the world over a long period shows warming temperatures and that could not be random. I am not sure I can do this question justice but will say it is not just statistics, but about climate and weather processes - we can observe that nearby locations experience similar conditions, such that e.g. a cold air mass blowing across a region is not observed to cause specific locations to result in one place being cold, but nearby locations are not - other than where other geographic factors come into play like elevation, orientation, vegetation. And where those differences exist it is evident in the weather records of those places; it won't be randomly changing. The local conditions make their own local baseline from which change and trends of change can be observed. The number of samples matters of course - a single sample, or too few, for the whole planet would not give a valid result, but for these purposes there are (IIUC) more than 30,000 that qualify as long running and reliable. If I understand correctly averaging comes with uncertainty range - that decreases with the number of samples. It would be possible to select from weather station data in order to be deliberately biased - but because those showing cooling trends are so few (are there any?) you would have to exclude most records to NOT get a warming trend. I think basic honesty and a professional attitude is the default; presumption of incompetence or bias built into the supposed "skepticism" opponents of climate responsibility and action use are vile in my view.

-

Tech Giants Shutting Down Violent Social Media Cesspools

I think popular entertainment and the distorted representations of "reality" it provides - probably contributes; people spend a lot of time in the fantasy land of media news, entertainment and advertising - and the lines between those are increasingly blurred. They are also more and more tailored and targeted, to engage the hopes and fears and beliefs various sectional groups of people hold, such that any editorial balance is not within the 'feeds', but with the diversity of different 'feeds'; increasingly our preferred views get reinforced unless we make an effort to sample other sources of information. I think our societies have always run in step with and promoted rather fanciful and self serving and self congratulatory stories of "how things work"; heroes rising up, taking matters into their own hand, saving the innocent, the day, the nation, and exacting revenge, is a popular theme anytime. But with partisan media - who was it predicted the political parties of the future will be media companies? - other media telling it differently to a different audience are portrayed as enemies and untrustworthy, preventing, not enabling an informed, balanced view, let alone treating differences as legitimately different opinion. The supposed Constitutional "right" to take up arms against their own government may add to willingness of fired up citizens to engage in direct action in the USA, in ways other nations with elected governments and rule of law do not - I say "supposed right" because it would only be a right ever upheld if the revolution succeeds... making the USA no different to any other nation, where insurrection is always criminal, with the notable exception of where it succeeds.

-

Trump Pressures Raffensperger to Commit Fraud

I think Trump's actions were criminal as well as dangerously irresponsible. In any nation where rule of law, truth and justice (and fair elections) are held up as their strengths and virtues, those holding relevant offices failing to address this behavior is... dangerously irresponsible. Possibly criminal in turn?

-

Abiogenesis and Chemical Evolution.

A question for science based enquiry rather than a demonstrated theory? A scientific work in progress? It stands out as the only credible option - any panspermia, intelligent creation just shifts the goalposts back to how life or Gods began - but it hasn't been demonstrated. Abiogenesis is not the same as Evolution; we have good evidence of Evolution but none (excluding existing life as evidence) for Abiogenesis. Even demonstrating an example of it (say in a lab) doesn't demonstrate that was how life on Earth actually began, but would demonstrate that it is possible. So much room to argue about it - lab conditions are not going to be precisely the conditions, just a best imitation, that includes some intelligent (human) interventions, if just to raise the odds. But I suspect it may be something that only gets resolved indirectly, using modeling to determine possible chemical pathways. Certainly there is ongoing work on those possible chemical pathways. Most recently, from Scripps Research -

-

Perceived disaster risk vs. actual disaster risk

Being known as a place that is free from disasters could lead to disaster if too many people from disaster prone regions try and move there. Walls and fences and border patrols can only do so much. In a trade connected and dependent world the problems of one region can and will impact other regions . But conversely, assistance from other parts of the world can flow back to alleviate that - if only to prevent the spread.

-

Nuclear energy vs. renewable energy

Even 5 years ago I might have agreed but battery R&D has become a truly massive deal; the players in that game are serious and are seriously well funded. It may not be wise to put all hope in them succeeding spectacularly but assuming they must fail, with perhaps a decade before growth of solar and wind starts forcing the issue, seems especially pessimistic. 100% is overly optimistic - and most larger grids are unlikely to ever be 100% any one thing - but nothing in this arena is staying the same long enough to base future projections on past performance. Batteries in the pipeline in Australia are reaching towards totals of GW of power and GWh of storage, already more than 10 times the electricity market operator's predictions made just 4 years ago - and causing plans for new gas plants to be deferred or shelved. It has been suggested that South Australia - admittedly especially good solar and wind - already has about 1/10th of the storage capacity to run at 100% RE. Some pumped hydro is coming along too. I think if we can do cars with batteries then cities stop looking so difficult - each car will have more battery storage than most homes and many small businesses need to run overnight from rooftop solar. Perhaps better so for warmer, sunny climates than Canada's Winters, which may need other solutions in addition. It will be to the advantage of low emissions committed grid operators to have lots of EV's plugged in when not in use rather than fast charged and disconnected. This will be both to vary charging rates to smooth supply (and demand) variability and (under mutually agreed terms with day to day consumer choice) get access to a portion of that stored energy. Every office and street car parking space with an EV charge connection will be worth something to power companies, something more valuable than mere convenience to customers.

-

Nuclear energy vs. renewable energy

Solar using mirrors work okay and can include thermal storage, usually molten salt - But I suspect the inclusion of storage has been premature and has not been good economically for these kinds of solar plants - in the absence of a price premium for that stored power. As the proportion of wind and solar grows the value of on demand power to fill the gaps will become more apparent. That will not be a market that suits nuclear; undercut on price during the day and forced to wring the bulk of revenues out of what remains - and that is a market for fast response, on demand power, not steady baseload; nuclear will have competition, including batteries and pumped hydro and even evolving flexible industrial practices. Meanwhile big PV is doing daytime electricity cheaper than these kinds of plants and big batteries are getting cheaper too - about 90% drop in price for Lithium Ion in the past decade and there are extraordinary R&D efforts underway to do batteries better. Tech device makers, cordless tool makers, vehicle makers, renewable energy makers plus government agencies all want better and are spending big to do it. Recent advances in relevant sciences is coming up with the deep understandings and clever tools to make big improvements not just possible but likely - and whoever cracks the next best possible battery will get rich beyond imagination.

-

Extraterrestial life searching

We have no examples of other kinds of biology. Water, as well as the elements and precursor compounds terrestrial life rely upon, appears to be widespread through the known universe and on planets. Even as hypotheticals/theoreticals, other kinds of chemistry look problematic. We may be able to model possibilities and find something that could work to produce life, but so far as I know none look promising. We may find that even with water based/carbon based life there may only be limited ways self replicating complex biochemistry can arise, ie that alternatives to our RNA/DNA/protein based life as we know it may be very unlikely or even impossible.

-

Is global average temperature a useful or thermodynamically valid concept?

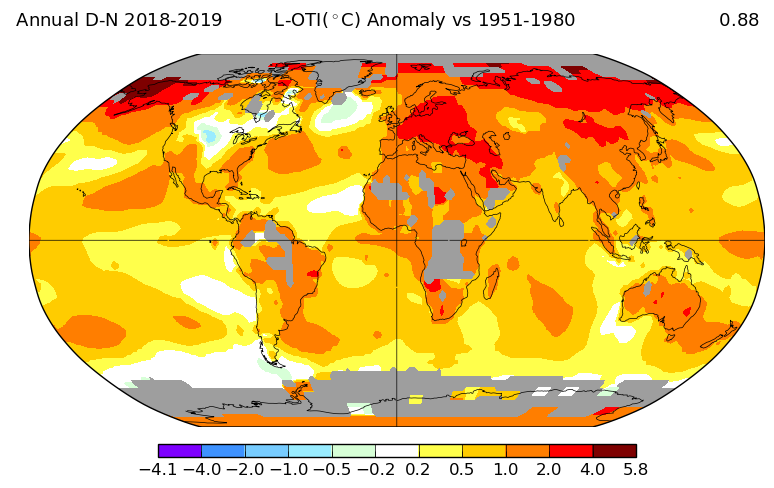

It has been useful to have a simple, single measure that shows global change but that global average is the tip of a very large iceberg. The last IPCC report - AR5 - ran to 2,000 pages, citing nearly 10,000 scientific studies. Claiming all concern over man made climate change is justified by one global average surface air temperature is not true. Admittedly most Presidents or Prime Ministers will not have read any full IPCC reports, but Synthesis reports and Summaries for Policymakers are reasonably accessible and understandable. Also they can call upon science agencies and experts to help them understand - as well as confirm that the science that produced those reports is valid. They can also run checks for evidence of fraud or conspiracy - but the "worst" anyone has managed is a few phrases in emails taken out of context and the fact that there are people in the UN who are dedicated to reducing global inequality and poverty and they want to incorporate those ends into climate policy. The use of global average surface temperatures may be more accident of history; a whole lot of local temperature records - minimums and maximums mostly - being in existence when climate change became a subject for study offered a way to find out if the world is warming (or cooling). At it's most basic it is a way to confirm or not that global warming is actually taking place. Whether viewed as a history of warming that needs explanation or viewed as real world confirmation of theoretical understanding of The Greenhouse Effect and how it should be expected to change global heat balance when CO2 levels change, it does give confirmation. Dive into the data and variability across the world is there too ; it gets used in many different ways, including with respect to local and regional change. 2018-19 regional average temperature anomalies for example - But I think of all measures of real world change that most closely shows the heat gain from man made climate change, this one is best -

-

What's The Point Of Calculus??

I had a good mathematics teacher for a year at high school and for a brief time calculus was a joy. I haven't used it much since and so, have mostly forgotten. I do recall deriving the equation for the area of a circle using calculus - I think it was a test question - and that it seemed to be seamless in it's logic. Made a Pi starting from square one! I couldn't do it now but it was kind of reassuring. It may have contributed more to my trusting established knowledge rather than sparking great determination to personally confirm everything. I cannot work out the equation for area of a circle from first principles now but at the time I was all round impressed.

-

Some Planets may be better for life than Earth

It is all a bit too speculative or something for my liking. That some planets might be more likely than Earth for life - and for complex life - to develop seems a reasonable proposition. Knowing exactly what conditions those might be is going to be difficult, but even the assumption of milder, warmer, less extremes being "better" looks like overreaching. I don't think we know what "better" is. Could not extreme conditions and variability be more - not less - significant to evolution?

-

Can you be a scientist and still believe in religion?

Lots of subjects of scientific inquiry won't conflict with a lot of versions of religious faith. A sense of wonder that has religious aspect has been a significant motivation for scientific inquiry, often without leading to false conclusions despite the overlap. But there are those who's religious beliefs lead them to attempt to disprove the science that appears to conflict with their faith, sometimes honestly applying scientific methodology but often not. Those may well put their conclusion first and will dismiss the validity of science outright should that conflict look unresolvable. It should not be necessary to know what the author of scientific papers has for personal beliefs in order to judge the validity of what they publish.

-

Phosphine detected on Venus

It seems much more likely there is an unknown non-biological process making Phosphine than unknown biological processes. But news programs I've seen are hyping the "could be life" story - some with inclusion of appropriate skepticism but mostly not.

-

Strange self-induced feeling

My own experience says my memories and imagination can evoke emotions and my emotions can evoke physiological reactions. I can trigger the reaction by choosing to remember something. Do that enough and I expect my brain will know where I am going with that and skip directly to it. I have no doubt people can trigger ASMR and other bodily responses at will - if they want to train themselves to it. Biofeedback comes to mind and I think Mindfulness type meditations can be healthy and beneficial - something I practice off and on. Perhaps for haptics - ie interfacing with our tech?

-

The Killing of George Floyd: The Last Straw?

I may not have worded it well, but I was not condoning police doing non-judicial "punishment"; quite the opposite. It is more evidence of failure of good governance. I expect that because of the primary reason for the protest there is a lot of ill will, more than many protests for other causes, no doubt from both directions - loyalty and sympathy to the police involved, irrespective of circumstances by many of their colleagues amongst police, distrust and anger at the police amongst protesters. That is not a good start, even for those intent on peaceful but determined protest or for police who think they have a point. There will be hotheads, even where there are not organised provocateurs or smash and grab criminals or police who think a show of overwhelming force - which is likely to be as ill aimed as random rocks thrown at police lines - is the correct response. Which can inflame rather than quell. If police want to operate with a de-facto blanket immunity from prosecution - and from the outside it looks like they do - they have to police their own internally, with zero tolerance that, if they cannot stomach criminal prosecution of their own, forces the unsuitable, incompetent and criminal out before they do too much damage. I have not seen much evidence of that in the police where I live, nor in the USA.

-

The Killing of George Floyd: The Last Straw?

I doubt there was intent to murder and likely the cop thought what he was doing would not kill the man - especially with bystanders recording. A bit of time honored unofficial "teach the scum a lesson", perhaps intended for the bystanders more than George Floyd, but gone wrong? Perhaps every attempt George made to struggle and shift to get a breath was taken as defiance - and so he was held down harder and longer? The rioting and destruction of property is counterproductive of course - and it won't matter that the vast majority of protest was/is peaceful. I don't know how Americans will reconcile their own history re Boston Tea Party being celebrated with property destruction as protest being innately wrong now; my own view is it WAS wrong back then too. I tend to see social unrest as inherently chaotic and easily incited to destruction and violence and it is potentially hugely expensive - that if legitimate and widespread grievances are not dealt with that kind of outcome becomes more likely. Not that property destruction is legitimate or that it will get the results wanted, but that it is a predictable outcome that good governance prevents.

-

Why Can't We With Water?

These kinds of schemes have been proposed again and again - some in great detail; they are not failing for lack of imagination. But I would not call assessing such plans on their merits and finding them wanting defeatism; that very ability to use foresight and understand what will and won't work before committing valuable resources is important progress. And besides the many schemes that are found wanting there will be projects that do pass, potentially more as engineering capability advances. Flood mitigation dams do work in many events that would cause flooding even if they can still be overwhelmed. The most effective solution - and most ignored - is to use foresight and stop building vulnerable infrastructure in flood prone areas. I would call that realism from applying intelligence and foresight to planning, rather than call it defeatism.

-

Why Can't We With Water?

This is hardly a new idea that no-one has thought of before. There are archives full of proposals for diverting flood water long distances to more arid but potentially agriculturally productive areas. They almost always fail on grounds of engineering difficulty and the high costs of overcoming them. Simply, the volumes of water during floods is enormous, far exceeding what any pipes or canals could manage. Leaving aside the transporting of that water to other regions and just looking at pumping water away as flood control we face the issue of just how much volume of water that will be. Consider a flood - how that volume of water flow compares to the normal watercourses. A smallish river will have much more flow than a large pipe or canal can carry and the volume during a flood far exceeds that capacity. Dams up stream are often used (and preferred) for flood mitigation - they catch a large part of the water before it reaches vulnerable cities and towns and bleed it away more slowly after the rains stop. These also work well for other water uses - at higher elevations it can be delivered for irrigation or town water supply to places downstream. As soon as you try to deliver it to higher elevations - or over them if intended for more distant regions - the costs and engineering difficulties rise. From US Geological Survey, (USGS)an example of how much more water flows due to rain events, in this case a modest 2 inches (52mm) in one day. Flow rate increased over to 150 times of base flow rate - Serious floods make that look small change. There are environmental consequences to flood mitigation and diverting water for agriculture - flood plains with ecosystems that rely on those floods are often much changed by human uses, uses that are disrupted by flooding. Human uses almost always take priority. But even all those mitigation efforts are routinely overwhelmed during serious rain events.

-

Alternative power sources megathread?

Most solar panels are made to cope with some hail - ours have survived numerous storms with hail, occasionally large enough to damage vehicles. Very large hail can still damage them - but we need to put that in perspective; very large hail damages all manner of things and replacing a few solar panels is not so common or such a big deal as to require a rethink of how solar power is done. My understanding is that solar installers did a lot of removal of panels after serious hailstorms in Brisbane Australia in order that roofers could fix damaged roofs - only to put the same panels back. Very few were damaged. Interesting to note that heat pump hot water systems are now similar in cost to passive solar hot water systems, have very low power usage and are reliable. Homes with solar electricity would probably not need extra solar power if they are used; our home already sends several times more power back to the grid than we consume and hot water systems are well suited to scheduled operation during the middle of each day or whenever solar electricity supply is exceeding usage.

-

Why do humans walk upright?

No need for invoking any directing of mutations or motivations for bodily change. Some people think that. I don't. I wonder if that is an academic holdover from the idea that because body hair has no significant survival function (which is a false premise), those ancestors with less of it had a metabolic advantage and therefore over many generations it got lost - and this is something still going on. The problem with that is that it has a continuing sensory function, extending our sense of touch beyond the skin - and is a principle component of the skin's ability to feel things; more sensitive I would argue as small hairs than as dense fur. ie humans gained improved sensory acuity. I think there are problems with invoking sexual selection too - what kind of sexual selection results in traits that primarily and profoundly affect juveniles in ways that are detrimental? That might be unique if so. Human juveniles all universally develop without fur, whilst only in adults are there significant differences - which suggests whatever evolutionary events caused it is in our entire species not responsible for the variations amongst modern human adults. Personally I find the notion that it was specific mutations that resulted in distinct furless variants pretty much as soon as they appeared (or, if recessive, when supplied by both parents) to be compelling - and they did okay and survived as a variant because they were members of groups of intelligent problem solvers. Or perhaps their parents did some of the problem solving; caring for vulnerable young is kind of fundamental. Why the furred variants did not survive - the natural selection part of evolution - seems a more pertinent question. But this is taking this away from bipedality into hairlessness - something I've had a long running interest in and have (as might be evident) my own speculations about. Yet that matter of degree did result in a unique evolutionary history - whilst all such histories are unique I suggest that our line of intelligent tool users are more unique. I cannot really equate examples of chimpanzee tool use with what our tool using hominid forebears could do - they took it to a whole, unique new level that impacted and improved survival abilities ever after.

-

Why do humans walk upright?

Tool use per se is not unique but hominid evolution diverged in unique ways because of it. Having the early tool use improved the survival abilities of the very hominids that were progenitors of the ancestors with improved cognitive abilities, capable of more elaborate tool use. And I said "intelligent" and "problem solving" as well as tool making/using - and intelligence and problem solving are not unique either, but the combination and the accumulated benefits and results in homo sapiens are.

-

Why do humans walk upright?

I would argue that Howsois has a good point: as I see it evolution in tool using hominids has indeed been unique. Whether that is the basis for becoming bipedal is still a question - so I don't necessarily support the conclusion that it did, but I think it has been pivotal to the evolution and success of the homo sapiens variant. I would like to read the rest before looking specifically at the walking upright trait. I think intelligent, problem solving tool makers can and did overcome limitations that would otherwise seriously reduce evolutionary fitness - in ways no other evolutionary line has. It does look unique to our evolutionary line. Example - fire and clothing and built shelters overcoming the disadvantages from lack of fur. Not just compensating but overcompensating in ways that created significant advantages - in this case that allow migration into regions with climates that would have been unlivable even with fur.