Everything posted by joigus

-

What Youtube videos are you watching now or have you watched recently?

- How Spin of Elementary Particles Sources Gravity Question

Very powerful argument! Absolutely right, in connection with Riemannian and pseudo-Riemannian geometries the word "intrinsic" means exactly that.- How Spin of Elementary Particles Sources Gravity Question

Yeah. To tell you the truth, I found the wikipedia article a tad ambiguous about whether it's "standalone" or it's "contributes to". @swansont had a similar point to make, besides the weakness of an only-spin source. But AFAIK too, you're right. Spinors cannot be represented by 4-vectors. After looking through the provided papers, it seems clear that none of the authors (related to such idea by the Wikipedia article) mean to say that spin be the one and only source of gravitation. Rather, they set out to find subtle effects of gravity on spin systems safely above the Plankian scale.- How Spin of Elementary Particles Sources Gravity Question

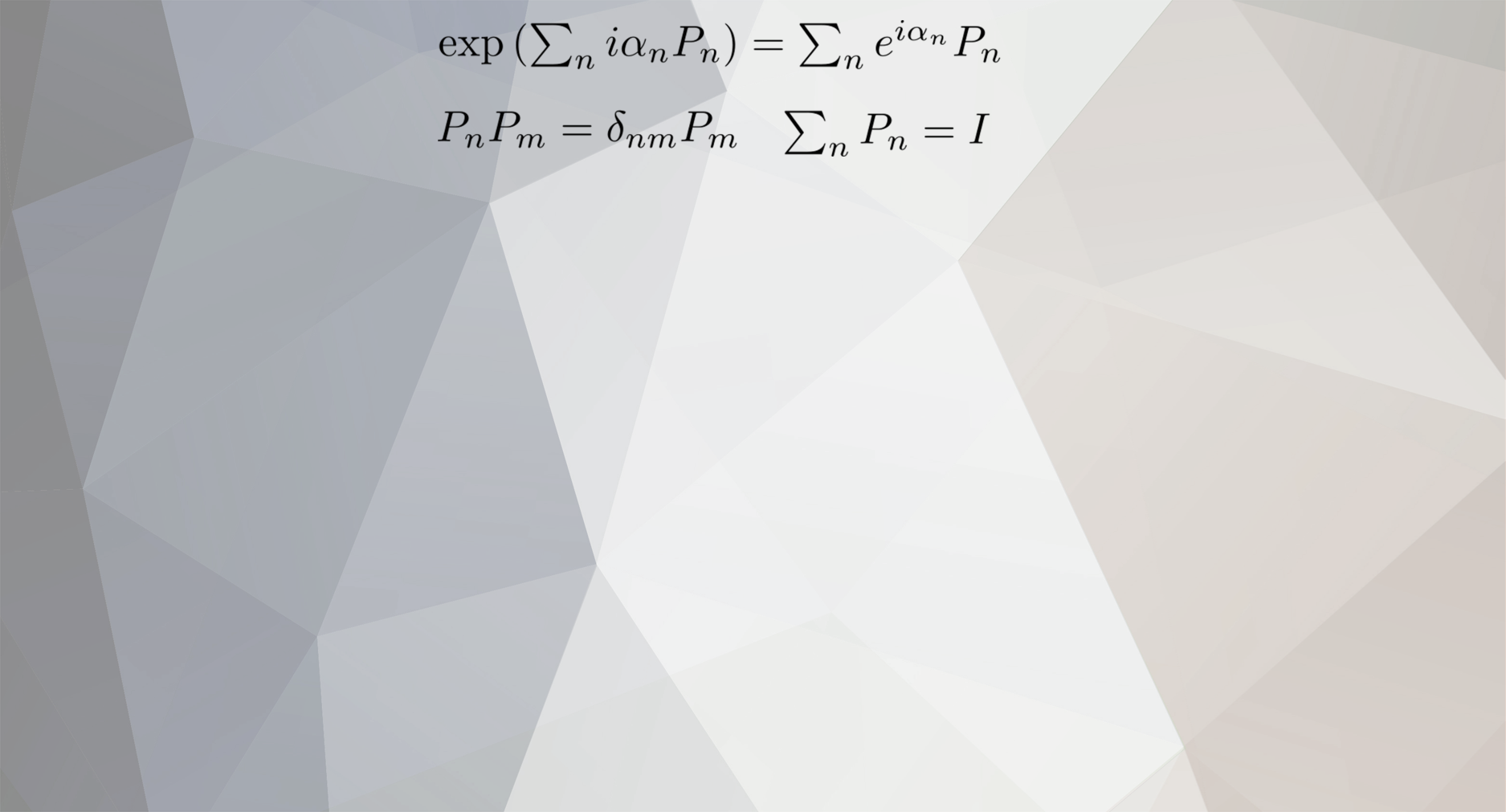

As said, suggested, implied: Angular momentum has energy. Energy sources gravity. Ergo, Angular momentum sources gravity. At the moment, we don't know whether the words "quantum gravity" are akin to what people once used to say: "elastic properties of the luminiferous ether". It could well be the case that these words finally have to be abandoned. There is also a spin formalism for general relativity. So, in a way, all of GR is about spin. This is because spinors are more basic objects than space-time 4-vectors (for every 4-vector, or event, there are two spinors representing it).- What Does the Pilot Wave Physically Represent?

Aaah... This sounds more like it. Although I wouldn't call the various equations coming from the Schrödinger equation "constitutive equations". Constitutive equations in physics implement properties of the medium, while the Bohmian wave implements properties of the system under study in reaction to that medium. After all, they come from a simple change of variables in the Schrödinger equation. But maybe that's just a matter of words. I'm not surprised that the theory in its form of particle + wave does not work. That point-like particles are inconsistent with relativity has been known for a long time. So long a time that the scientific community as a whole seems to have forgotten, as the whole business painfully ground to a halt during the first decades of the 20th century. A topological scalar field consistent with local gauge invariance might do the required jobs. A point particle is hopeless.- What Does the Pilot Wave Physically Represent?

In the De Broglie-Bohm theory the pilot wave is source of a so-called quantum potential, that must be added to all other potentials acting on the particle. This quantum potential produces infinite repulsion in places where \( R=\left|\psi\right|^{2} = 0 \) (interference), as its form is proportional to \( \frac{\nabla²R}{R} \). You are using "configuration space" in a sense that is not familiar to me. "Configuration space" in mechanics usually refers to the set of all accessible positions. I don't know what you mean by "a real constraint structure". Constraints in mechanics are obstructions to how the system can move (holonomic constraints), like a particle being forced to be at the tip of a rigid rod, etc. Your vocabulary is a bit weird, and I at least do not understand what you mean. The theory has its virtues, but makes calculations extremely awkward, not least the ones pointed out by @Mordred . Besides Pauli's objections, Einstein also seems to have said that it goes against every physical intuition to conceive of something that acts on other physical entities, but cannot be acted upon. John Bell was one of its most notorious advocates. He didn't say it must be correct. He said it must be studied. </my two cents> IMO there is the possibility that it's but a version of a more elegant idea that we haven't been able to fathom so far. Among other things, point particles cannot carry irreducible representations of the relevant space-time groups, so it could be the case that there's a generalisation of it having to do with scalars, rather than point-like densities. That seems healthier in the context of field theory. </>- "Wave if you're human"

For me it's number 3. I can't recall how many times I've listened to it. Especially the 3rd movement. I have no words to describe the experience. But it's all of the Brandenburg concertos really. And it's Bach. Always Bach. The cello suites, the Goldberg variations, Magnificat... There's something about Bach that makes it seem as if all of music were already in it. Haven't we had an exchange about Bach before? I've noticed exactly the same feature. I must say I lack a criterion to judge so-called generative AI. How "generative" generative AI actually is? I don't know. I've skimmed through news about some generative AI packages genuinely doing seminal work in mathematics, for example. I can't significantly commit an opinion on that, TBH.- Today I Learned

Today I learned that "Today I Learned" can also be used to discuss whether I actually learned something or not. 🫠 Cheers! Very interesting, and impossible to watch from where I stand. Thank you.- Refutation of a.is regarding gravity that is independent of mass.

I propose to remove the "work" bit from anything speculative coming from AI. It would be just a "frame". That is, the "framework" without the "work". "I've been given a frame to talk about this" would be at least honest.- new perpetual motion machine , coppyrighted , with proof , and renewable energy tech , please read .

- How Far Reaching is Science?

I didn't say anything was or wasn't intended to set our future plans. I quite intentionally kept things quite unintentional. I said something else. Please take some time to read what I did say, or this is gonna take forever with you talking past me, instead of we talking past each other., as you claim- There is no Next

As @studiot pointed out, (1): This is not classical physics. And (2): "nextness" depends on the number system. There is a next number in the naturals, the integers, all the finite arithmetics, etc. There isn't in the reals or the rationals. The question of whether there is a "next point" in physical space is equivalent to whether space is discrete. Is that what you mean, @Farid ?- How Far Reaching is Science?

I don't see how setting our future goals is a religious aspiration. Religion is more about inevitability and submission. Not a whole lot to do with changing your future. Religion has no tools at all, as praying and lamenting are not tools.- Why we observe only retarded gravitational waves, not advanced?

The boundary conditions it would require (not just for gravitational waves, but for any full-fledged macroscopic waves of any kind to exist) would be waves starting at spatial infinity in phase. They are unphysical. And yes, the reason is entropic in nature. We need to solve the arrow-of-time problem before we can answer that question. In the famous Wheeler-Feynman problem of electrodynamics as a half-advanced, half-retarded field, the boundary conditions were totally ad hoc, as the authors were keenly aware of, that there was a perfect EM absorber at spatial infinity. It is my intuition that it would cause serious problems with causality too (what would have caused that identical physical condition infinitely far apart in the first place?), but that a story for another day. All of this IIRC.- How Far Reaching is Science?

It doesn't. Understanding whether the human species has been taming itself for the last hundred thousand years is one thing. Setting our future goals, ethically, pragmatically; and acting in such a way that those goals are achieved, is a very different one. As different as studying the history of a city and doing urban planning for that city.- How Far Reaching is Science?

I don't think so. Science would help us understand in what direction we're going as a species in the ballpark of 10⁴-10⁵ years. Understanding, however roughly, in what direction we're going doesn't depend on what direction we wish to go.- Theory of everything (Jros)

Let alone a "theory of everything". The world of patents would come crashing down, as everything would already be subject of a patent forever and ever.- How Far Reaching is Science?

I concur with the argument shared by many here that science generally gives us a better understanding of Nature. In a nutshell, and as said before, how we use that is rather a matter of scientific, engineering, etc ethics. Perhaps however it's worth pointing out that there is a hypothesis currently undergoing study in anthropology and peripheral sciences that posits the possibility that a slow adaptive process of self-taming has been going on for a long time (in terms of human evolution, so think 10⁴-10⁵ years). This is known as the self-taming hypothesis or self domestication. Were it confirmed at some point, that would mean that the answers to those problems the OP mentions are subject to some kind of self-correcting adaptive process that science itself can study, confirm, or falsify. That would mean science can even help us understand whether or not we're going (or likely to be going) in the direction the OP hopes for.- The Official JOKES SECTION :)

It's "divergence", not "diversion". And that only accounts for half the nature of light. The other half is: "The four-dimensional divergence of the dual of the previous tensor is the 4-current of electric charge". The second one account for the sources of light. In other words, \[ dF=0 \] \[ d^{*}F=\mu_{0}j \] (Not only light, I must say, but every other electromagnetic phenomenon, like the properties of capacitors). Not very droll, I know...- Is Time Instant?

A similar question would be, "is space point-like?" We prefer to say, "is time a continuum, or is it discrete (ie, made up of little 'jolts' of time)"? @geordief , IMO, asked the right question. It is perhaps telling that the HUP doesn't allow us to "see" this point-like structure of time, provided it makes any sense.- Cosmological redshift is the result of time speeding up

Again: What time symmetry? I'm not asking what it is about, but which particular transformation you are thinking of. Eg, Lorentz transformations are about space and time, but they are a very specific type of symmetry. We need you to be more specific.- Gravity.

The best way I know of overcoming gravity is to jump in a vacuum in the field of a massive object. Automobiles don't usually do that. Generally you must get as far away from a road as it's possible to get. Special planes do, and spaceships. Like this: The flight that brings space weightlessness to EarthYou don’t have to go to space to feel the weightlessness of orbit. Sue Nelson joins a special flight that puts its passengers into zero gravity – at least for a few seconds.You're mixing up overcoming gravity with opposing gravity. Very different. @studiot is right. You don't sound like an engineer at all.- Could there be a "Communication Theorem" instead of a "No-Communication Theorem"

Do you mean that the no-communication theorem would be violated and signaling between distant factors of an entangled state would be possible? If that were the case, I wouldn't call it a "communication theorem". It would simply be that the no-communication theorem doesn't hold. Eg, we don't have a theorem that says 7-body systems exist. The context of the quantum NCT I think is very different. If I remember correctly, communication back and forth through the ER bridge is not possible. All of this is, of course, just theoretical speculation, but if I had to bet, I'd say "no, it doesn't happen".- Cosmological redshift is the result of time speeding up

What time symmetry? Translational? Reparametrisations? Inversions? Combinations of some/all/a few of those? You see, "time symmetry" doesn't mean anything in and of itself.- Cosmological redshift is the result of time speeding up

I must say I haven't leafed through many of those, but I get the picture... YT thumbnails can be pretty awful. But Veritasium's content is worth the aesthetic displeasure. - How Spin of Elementary Particles Sources Gravity Question

Important Information

We have placed cookies on your device to help make this website better. You can adjust your cookie settings, otherwise we'll assume you're okay to continue.