Everything posted by joigus

-

Does somebody study complex energy particle ?

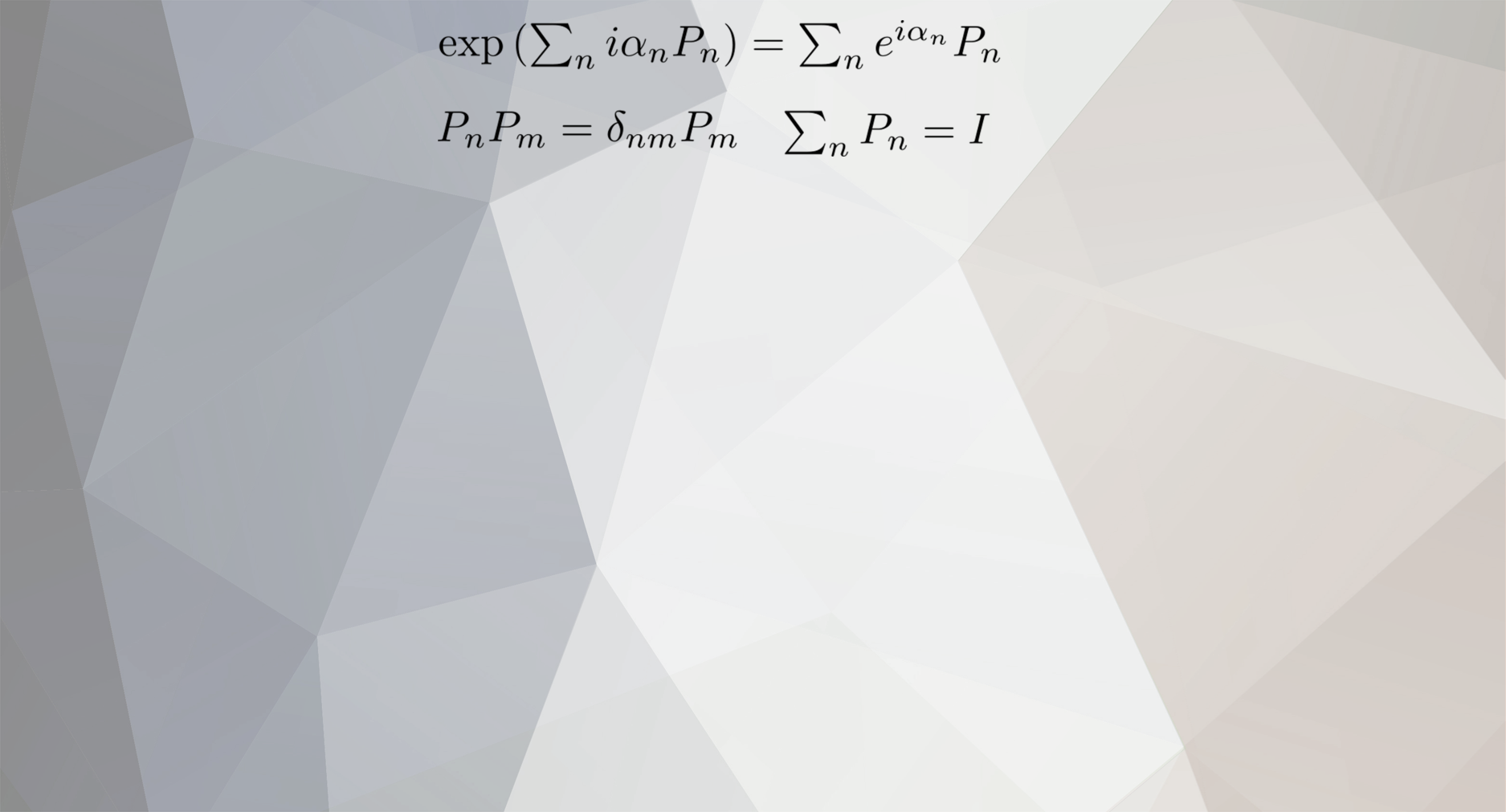

You would have a violation of unitarity, which isn't a good thing. All relativistic state vectors for massive particles have a factor that in natural units looks like, \[ e^{-imt} \] Assuming, \[ m=\textrm{Re}\left(m\right)+i\textrm{Im}\left(m\right) \] You would get, \[ e^{-imt}=e^{-i\textrm{Re}\left(m\right)t}e^{\textrm{Im}\left(m\right)t} \] Now, suppose you have \( \textrm{Im}\left(m\right)>0 \) => runaway solution everywhere for growing t. But if \( \textrm{Im}\left(m\right)<0 \) you have a vanishing solution everywhere for growing t. Both violate unitarity, so you have a much bigger problem than with a negative mass. Negative masses are no good because of decay. Particles would spontaneously decay to lower levels, 'more negative'-mass states. But non-unitarity is a non-starter. I'm sure there are more other arguments but, to me, that would be enough.

-

Can Someone Explain Quark Binding Energy?

No way. I wanted to make a contribution here. I was thinking about mentioning 'residual QCD forces' to complete the picture (similar to mesonic states flying to and fro), and @MigL beats me to the punch.

-

Are we evolving towards a pan-language? (Linguistics)

OK. Thanks for your answer, but you're wearing your political glasses. I didn't mean 'evolving' as 'going towards something good.' I meant it as 'going towards something different.' Believe me, I pain for the loss too. Interesting. Why?

-

Are we evolving towards a pan-language? (Linguistics)

Simple enough: Are we? It seems inevitable that we are. Then languages like Quechua or Walpiri will be reduced to the roles that now play Hittite or Assyrian. Or will we evolve into a multi-dialectal pansociety? Local versions of the same, say, English; but with people being able to understand each other all over the Earth. Will we evolve towards a bi-polar, tripolar, etc. model? What do you think? And why?

-

What's wrong with Progressivism?

The progressive element is essential in any society that pursues betterment of the human condition. Progressivism, as a tenet, is a good theoretical starting point. Problem is: Self-declared progressive parties vie for power and control of the budget, like everybody else. If under pressure, they will act in ways that contradict their 'theoretical principles,' provided working politicians really have some of those. Whatever their tenets are, and out of this pressure to out-elbow everybody else, they will not hesitate to re-define their concepts. As MigL said,

-

The Futility of Exoplanet Biosignatures

You set your standards very high, @beecee. Finding a fossil is hard enough on Earth! Just a molecule that couldn't conceivably have been produced by geology wouldn't be enough?

-

The Physicist and the Philsopher:

I find it impossible to disagree with that. It is true, though, that your average scientist has been concerned about philosophy at least at some point rather more often than your average accountant, for example. But @TheVat's point is well taken which is, I think, in a similar direction. Funny that not many non-experts would commit an opinion in, say, computer science; while most of us have an opinion on philosophical questions no matter what our level of familiarity with the subject may be. The questions that philosophy more intensely deals with are at the core of what every human being wants to know. It seems that Einstein ruffled more philosophical feathers than those of Bergson, because I remember another episode with Rudolf Carnap about the nature of time. My --totally partial view of what happened is: Einstein said he was deeply concerned about the nature of time. Aaah, but definitions are crucial. It is a common misconception that definitions are arbitrary. Good definitions cut, and melt, and grind, and have power. They synthesise hours and hours of previous observation and intuition. Good point! My hands are down.

-

The Futility of Exoplanet Biosignatures

So we need a theory of life, or a definition at least. In the absence of that, what chemical would our distinguished members consider to be a dead giveaway? --Puns aside.

-

The Physicist and the Philsopher:

I find pretty much the same problem with any proposition including the words 'as it really is.' As if there's some bogus way, and then there's the 'really real' one. That's as much as I can say without actually reading the book.

-

Do somebody study negative energy particle ?

There have been so many puzzles in theoretical physics, and so many more people working on it than ever before, that almost every conceivable idea of that kind has already been tried. Dirac tried with his sea of negative-energy electrons, but it was proven that Dirac's vacuum would be unstable, and wouldn't last. A vacuum in quantum field theory with negative-energy quanta is nothing like our universe's.

-

Passion for Science

Only true knowledge brings you true emotion. So I understand. Other people experience it with less of an outpour, but every bit as intense and authentic.

-

How do oceans affect the Earth's crust?

Sorry. Wires got crossed with another conversation.

-

How do oceans affect the Earth's crust?

CaO2 is a peroxide, actually. Just to be precise.

-

How do oceans affect the Earth's crust?

Good point.

-

How do oceans affect the Earth's crust?

I'm out of my depth here --no pun intended. I'd heard that when temperature in the mantle goes down below 650º, water can start leaking into the deeper mantle and essentially disappear from the water cycle. If I understand correctly, the formation of hydrous minerals is essential for this removal. I understand @exchemist's example of CaO2 as simply an example that if you include oxides, you can account for this. I've been looking for online credible literature about the subject, and I've found this: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/hydrous-mineral#:~:text=The hydrous minerals like rock,water in a shallow sea. I won't pretend I understand every argument there, but it seems as if we're at some point in a shift of paradigm here, and people are pushing the boundaries of the depths at which it's thought that this hydration can occur. Am I reading this correctly?

-

First use of 'soil' from the Moon to grow plants.

Brilliant point. I hadn't thought about it.

-

First use of 'soil' from the Moon to grow plants.

As @Sensei said, regolith is not a true soil. Google: "why is regolith not a true soil" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regolith Even on Earth, where molecular nitrogen is very abundant in the atmosphere, we need nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Only physical processes and few and very special organisms can break the N2 triple bond. I suppose @Genady's picture is correct that, once the nutrients from the seeds run out, the plant cells simply didn't find the nitrogen to synthesize their proteins and nucleic acids. I would assume lunar regolith is poor in phosphorus too, but I'm not sure. Interesting news.

-

NSF & EFT announcement on May 12, 2022

Thanks. Very interesting!

-

How do oceans affect the Earth's crust?

It's a minor effect in comparison to volcanism, only noticeable at the time-scale of hundreds of millions? billions? of years. A part of the water gets recycled to the atmosphere as you say, but a small fraction is incorporated as hydrous minerals, from what I know. I think this is the original find: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2019GC008232 Does that check with you? I'm very interested in learning what you think.

-

How do oceans affect the Earth's crust?

Just to add to what other members have said. It's perhaps interesting to use Venus as a comparison: a planet that should have had plate tectonics --it has very active vulcanism, has the right size, etc-- but doesn't. Google: "why doesn't Venus have plate tectonics?" As stated above, the role of water as lubricant in the subduction zones is thought to be of critical importance. It also leaks into the mantle, so the oceans are ever so slowly being depleted.

-

NSF & EFT announcement on May 12, 2022

Totally spot on. In fact, part of the light that we see is just behind the BH from the observer. The back of the BH from the observer may be the worst place to try to hide from them.

-

NSF & EFT announcement on May 12, 2022

To my --totally untrained in interpreting astrophysical data-- eyes, I would say accidental changes in density in the accretion disc are to be expected. From the video talk that @Genady linked to, the experts make more of an issue of the way in which those gradients move --than of the fact that they're there at all--, if I understood correctly. The more mathematical-physicist type that talks there --Ziri Younsi-- states that all observations agree with Einstein's version of GR impressively well. The 'groundbreaking' part of it is more due to the achievement than to any big surprises, I think.

-

NSF & EFT announcement on May 12, 2022

Thanks. Merging suggested:

-

NSF & EFT announcement on May 12, 2022

Thanks!

-

How much of me is in my memory?

Does 'me' have parts?