Everything posted by joigus

-

Why is a fine-tuned universe a problem?

I don't think one can say that not having found squarks or photinos in LHC does away with M theory for good. There's a mixed blessing in superstring theory, which is: There's so much freedom in the theory that it's very difficult to rule it out completely --I think--, almost as much as getting concrete predictions from it. As to supersymmetry, my comment is: High-mass predictions of superpartners are based on masses arising from spontaneous symmetry breaking. That's the only game in town now. But, what if there are other ways for a symmetry to be hidden? Supersymmetry is a very compelling idea. It's not just about superpartners. I think it goes deeper. It's about symmetries of space-time and internal symmetries. It relates both. Very compelling. Maybe we need to understand quantum mechanics better in order to see what it's telling us. I'm not saying it must be pushed forward at all costs, but I don't think we're done with trying it out just yet. I think I can argue in favour of SS a little more, but not now. 😫

-

Why is a fine-tuned universe a problem?

Yes. The ambitious (not toy models, like supersymmetric quantum mechanics, etc.) are called supersymmetric extensions of the standard model. There are several of those, depending on the number of so-called central charges. The simplest is known as minimal SS extension of the SM.

-

Why is a fine-tuned universe a problem?

When people say "string theory" what they really mean is "superstring theory" or "M theory" with SS. A theory of strings without supersymmetry is a non-starter. One of the reasons for this is that you need the fermionic diagrams to correct for the uncontrollable bosonic diagrams, to remove the fine tuning in the Higgs mass. The other is that the best-behaved QFTs are those with supersymmetry. They can be exactly solved or perturbatively convergent.

-

The Official JOKES SECTION :)

- How can information (Shannon) entropy decrease ?

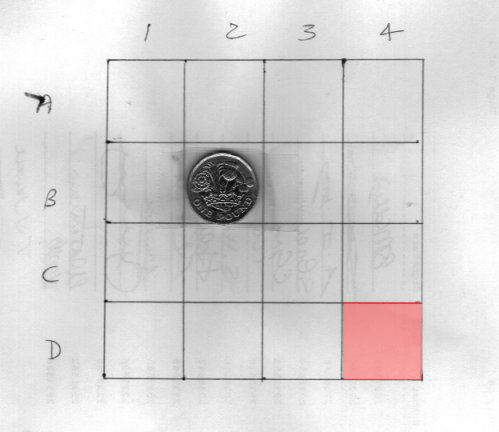

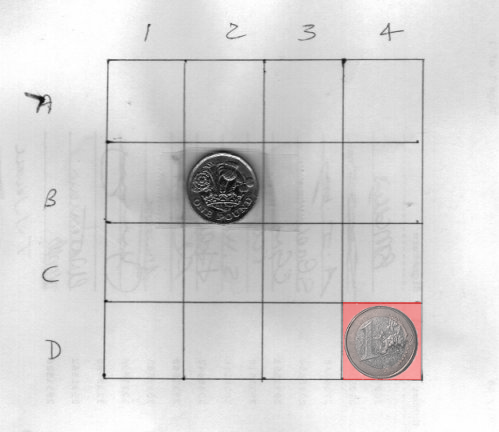

I think there are several aspects in which one could try to make this example more similar to what's going on in physics and, in particular, in computers. I'm no computer scientist, so don't take anything I say too seriously. I think interesting features are at play in thermodynamic systems that are not necessarily that relevant when it comes to computers. The most important one, IMO, is that computers are not generally set up in a way that they will end up being in a state of equilibrium. The other, perhaps equally important, is that the way in which circuits in a computer switch on and off is not ergodic, meaning that during a typical run of a program, the bit-states do not cover all possible configurations, let alone equally likely. I suppose --correct me if I'm wrong-- they will be more likely to run along some paths than others. And my intuition is that the sequence of configurations would have a strong dependence on initial conditions too, something that's not a characteristic of thermal-physics. Another feature that our toy example doesn't have, but both computers and thermodynamic systems share is, as @SuperSlim has been trying to tell us all along, evolution. So we would have to picture our system more like a table on which we're free to add and remove coins according to an updating law (evolution) that determines which square is occupied, and which is not, in an unpredictable way. If that's the case, I would find it easier to interpret Landauer's principle in the following --overly simplistic-- way. This would be a state frozen in time: Where you have to picture any number of coins compatible with available room as free to move about following an updating procedure. All squares are available to be "ocupied" with a microstate 0 or 1. At this point, the updating law (program) has yet to write a bit on a given square. Mind you, this concept could be applied to either RAM, ROM or SWAP memory. Now the program finally writes a bit. Whether it's midway during a calculation (for storing the value of a variable, for example), or to hard-disk memory, it takes some kind of process to hold the value there. It could be 0, or it could be 1. It's the holding that's important. I will denote this with a reddish hue: (Bit 0) Or: (Bit 1) At this point, the rest of the coins are free to occupy whatever other squares, as the case may be, except for that in position (D,4), which is occupied (whether it be 0 or 1 the bit that's occupying it), until it's freed again. This restricts lowers the entropy, because, for however long, the system has become more predictable. If I erase the bit, what does it mean? I think it means that I cease holding the value at (D,4) in position, the square being available again either for temporary use, or for more long-term one. I may be completely wrong, or perhaps oversimplifying too much, but please bear with me, as I'm groping towards understanding Landauer's principle on a physical basis. One final comment for the time being, I don't think you need evolution in order to define an entropy. Whenever you have a statistical system with a fixed number of states, as in @studiot frozen-in-time example, you can define an entropy as long as you have a way to asign probabilities to the different configurations.- How can information (Shannon) entropy decrease ?

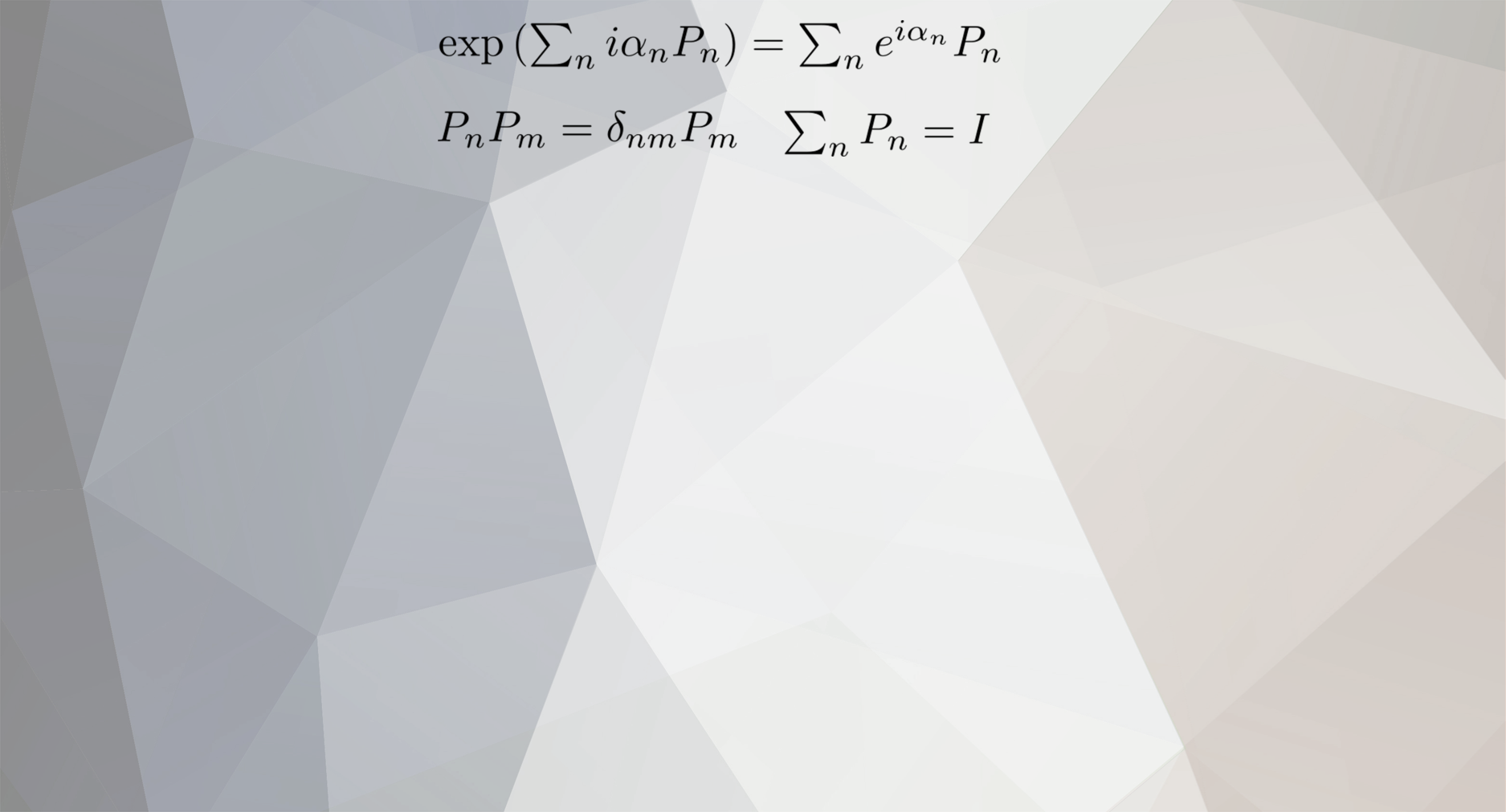

@Ghideon and @studiot. I think I know what both of you are getting at. Thank you for very constructive comments that go in the direction of elucidating something central here. -------------- Qualification: The "canonical" entropy \( -\sum_{i}p_{i}\ln p_{i} \) is not the only way you can define an entropy. We should be clear about this from the get-go. There are other definitions of entropy that you can try, and they happen to be useful, like the Rényi entropy, and still others. But once you have decided what form of entropy it is that characterizes the level of ignorance about your system in terms of your control parameters, the calculation of the entropy based on your knowledge of the system should be independent of how you arrive at this knowledge. --------------- But the way you arrive at that information is not neutral as to the heating of the rest of the universe! I'm calling the particular questions your "control parameters." It's very interesting what you both point out. Namely: that the coding of the answers (and presumably the physical process underlying it) strongly depends on the questions that you ask. Suppose we agree on a different, much-less-than-optimal set of questions: 1) Is the coin in square 1,1? 2) Is the coin in square 1,2? and so on. If you happen to find the coin in square 1,1 at the first try, then you have managed to get the entropy of the system to 0 by just asking one binary question, and in Ghideon's parlance, your string would be just 1. The way in which you arrive at the answer is more or less efficient (dissipates less "heat" so to speak), in this case, if you happen to be lucky. But the strings Ghideon proposes, I think, are really coding for the thermodynamic process that leads you to final state S=0. Not for the entropy. Does that make sense?- Is Torture Ever Right ?

No. Not you. I am the middleman (an intermediary in this bussiness with nothing at stake here), trying to think rationally, but trying not to think in a desperate kind of mood. The rest of it is my lame attempt at playing with words: "straw", "giant". etc. I don't think my argument was a straw man, as @dimreepr has correctly interpreted.- Is Torture Ever Right ?

I think it's more of a middleman with a giant hunger for thinking rationally without clutching at straws.- Is Torture Ever Right ?

This list really boils down to: 1. Use physical violence à la Corleone (1-6) 2. Use physical violence à la Torquemada (7) Which in turn, and except for matters of stylistic approach, both boil down to: 0. Use physical violence. One might as well list among them the "technique" of throwing a dead-horse's head into someone's bed. Even this last one seems to me far more imaginative, if similarly brutal. The direction in which I would like to move, which I would more devoutly wish all of us to explore, is not one that lists every single part of a human body on which one can inflict pain. That's not a very useful list, to me at least. I said it before: Using physical pain in its manifold forms is not the only perspective we can adopt. It strikes me how how much harder fiction writers have speculatively explored this possibility: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Clockwork_Orange_(novel)#Part_2:_The_Ludovico_Technique And how little effort we, people who love science, are willing to use to explore alternatives that could be more humane, more reasonable, and allegedly more efficient. Just a thought. It could be split to Speculations, if moderators deem it appropriate.- Sydney Horrific Shark Attack:

My best guess as to why this unfortunate event happened: Shark faced a bad season for favourite food, like, eg., sea lion. Pressed by hunger, tries getting nutrients from other source, even though it's not adecuate for shark's nutritional needs --humans have no blubber. I don't think the shark case is anywhere near the tiger case as to behavioural patterns. Just an educated guess on my part.- Is Torture Ever Right ?

Very interesting. Thank you. And seems to be the closest to hard evidence that any of us has contributed so far from the pragmatic --non-ethical-- point of view. ------ And now for something completely different... As long as we're heavily involved in devising thought experiments... Let me set up a totally hypothetical scenario. Suppose enough research is done that we learn there is a procedural pathway to have a person spill the beans no matter what compelling motivation they have to keep it secret by exciting some part of their brain. This part of the brain is the nucleus accumbens, which is related to pleasure, positive reinforcement, and the like. Completely hypothetical, mind you. So, in this hypothetical scenario, we've found out that, instead of best results being obtained by ramping up the pain circuitry; they are obtained by ramping up the pleasure circuitry. Would you still do it? Remember, the guy is scum, and you're set up for giving him the time of his life. But you get to save poor little girl in dark, damp basement. Would you still do it? Answer yourselves, more importantly than answer here.- How can information (Shannon) entropy decrease ?

This would be true in classical mechanics. Nevertheless, in classical mechanics you can still asign a measure to the phase space (space of possible states). So even in classical mechanics, which asigns a system infinitely many states, entropy is finite. Entropy is related to the measure of phase space: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entropy_(information_theory)#Measure_theory It is definitely not true when quantum mechanics makes an appearance. All systems are spatially finite. If they're finite, their momentum is quantized, and the basis of wave functions becomes a countable set. Also, there is no such a thing as non-informational DOF of a physical system. All DOF are on the same footing. There are two concepts of entropy; one is the fine-grained entropy, which corresponds to the volume (measure) of the phase space, and the coarse-grained entropy, which depends on how much information we have on the system. The total content of information is constant. It cannot be lost. INFORMATION = information - entropy = volume (phase space) Where by INFORMATION (in capitals) I mean the negative of fine-grained entropy; and by information (in lower-case letters) I mean the negative of coarse grained entropy. You're also confusing #(dimensions) with #(elements) = cardinal. Those are different things.- How can information (Shannon) entropy decrease ?

In the case you propose, entropy decreases in every step. 0) Initial entropy \[ 16\times\left(-\frac{1}{16}\log_{2}\frac{1}{16}\right)=\log_{2}2^{4}=4 \] 1) It's not in the first column (12 possibilities, assume equiprobable): \[ 4\times\left(-0\log_{2}0\right)+12\times\left(-\frac{1}{12}\log_{2}\frac{1}{12}\right)=\log_{2}12=\log_{2}4+\log_{2}3=2+\log_{2}3<4 \] 2) It's in the second column (4 possibilities, assume equiprobable): \[ 4\times\left(-\frac{1}{4}\log_{2}\frac{1}{4}\right)=\log_{2}4=2<2+\log_{2}3 \] 3) It's not in the first row (3 possibilities, assume equiprobable): \[ 3\times\left(-\frac{1}{3}\log_{2}\frac{1}{3}\right)=\log_{2}3<2+\log_{2}3 \] 4) It's in the second row (1 possibility, entropy is zero): \[ -1\log_{2}1=0<\log_{2}3 \] Entropy has decreased in every step, and there's nothing wrong with it. I'll think about this in more detail later. I think I see your point about the RAM circuit, and it reminds me of a question that somebody posed about Landauer's principle years ago. Very interesting! But I would have to go back to mentioned thread. One thing I can tell you for sure: You will have to increase the universe's entropy if you want to know where the coin is. There's no way around it: You have to look at the coins; for that you need light, and in focusing your light you will have to set some machinery in motion that will disturb the environment more than you order your system. So Shannon and Boltzmann are joined at the hip.- How can information (Shannon) entropy decrease ?

As I understand, Shannon entropy --apart from the trivial difference of being defined in base two, which makes it ln2-proportional to "physical entropy" \( -\sum_{i}p_{i}\ln p_{i} \), so that both are proportional-- is always referred to a part of the universe. A computer is always a part of the universe, so there is no problem for entropy to decrease in it. That's what Landauer's principle is telling us: When I erase a bit from a computer, I insist the certain circuit is in state 0. That makes the particular state of the circuit predictable. Its state is 0 with probability one, and thus I heat up the universe, because the entropy in my computer goes down. The entropy of a computer, whether classical (binary) or quantum (based on q-bits), or a set of N coins, or whatever other example for Shannon's entropy to be relevant, is but a part of the universe, so its entropy doesn't have to increase necessarily. I hope that's a satisfactory answer, if I understood you correctly, of course.- Do We Have Free Will?

Knock yourself out: https://www.scienceforums.net/search/?&q="free will"&search_and_or=or&search_in=titles&sortby=relevancy- Spooky experiences

I'm not an expert on this, but... I always try to formulate a rational explanation. When we are under stress, or the sensorial signals are somewhat scrambled, or both, we tend to try and make sense of what's going on. There's an ongoing dialogue between the different parts of our limbic system. In that dialogue the signals are processed in such a way that the salient information from the relational cortex --I'm kinda assuming here-- tends to be forced to fit in a dictionary of familiar words and concepts. Pareidolia may be the word?- Surface waves in a liquid

Landau-Lifshitz. Theory of Elasticity. Chapter 1, page 1. (My emphasis.) When solids are subject to strains and stresses, and shear tensions, they tend to recover their original configuration in a directional way. This justifies the introduction of directional vector fields that implement this behaviour. When fluids are subject to forces, they tend to recover their original configuration in a non-directional way. This, IMO, is what's led to the separation into two different disciplines. Fluids are also characterised by velocity fields (particles making up a fluid move about quite freely; while in a solid, that's not the case: there's no convection, etc.). Of course, nothing ever's quite that simple, is it? So @studiot's caveat is probably very relevant. There are strange things that fall outside these classical (19th-century) categories, like liquid crystals, which are both fluid and non-isotropic, but that's another matter.- Need to revise, nothing entering my brain after studying for few hrs today

1) Clean up your room 2) Then:- Gravitational Potential Energy in a 2 dimensional Universe

I missed that nuance. Thanks!!- Gravitational Potential Energy in a 2 dimensional Universe

I couldn't agree more. While the GR discussion, as well as alternatives/generalisations/toy-models is very interesting, perhaps @Vashta Nerada is interested in another level of discussion. Markus did say "deduce," but of course we all understand what he meant. I've crossed paths with him at least once in relation to this precise matter. And it hasn't scaped my attention that his signature displays Stokes' theorem in its most general differential-form form.- Neuroscience Teaching tools/learning materials

Whirlwind tour of evolutionary, genetic, behavioural, developmental/environmental bases of behaviour (25 lectures): Enjoy!- Gravitational Potential Energy in a 2 dimensional Universe

You just touched my soft spot. It is an interesting possibility, that I've tackled before in the way of a suggestion: That it's just possible that both time and space are multidimensional, but we (and other physical systems) may just be constrained to perceive it as 1+3-dimensional or, IOW, 1+a bundle of the rest, that we perceive as spatial+internal. It's just a speculation, of course, but a speculation that I think can be argued in favour of within the limits of mainstream, widely-accepted science. I'm not sure if anybody has proposed anything like this. My intuition is that somebody must have, because almost any idea you can conceive of has previously been considered by someone.- Darwin was only half right. EVERY animal evolved into the human being, not just the ape

Yeah. A nice guy who now and then decides to give some people this nicest of treatments: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/fatal-familial-insomnia/#:~:text=Fatal familial insomnia (FFI) is,significant physical and mental deterioration. Just because... Ooops, he wanted to play with the order of their nucleotides. This is one of the most horrible deaths you can think of. Nice going, God.- Zero is a number, and the big bang proves it.

Yeah, there were cyclic-universe models that AFAIK are not very much favoured by cosmologists today. It seems that cosmologies based on inflation (a period previous to the big-bang when extraordinary rates of expansion took place) are the preferred mechanism. That's because they have a considerable explanatory power of the present state of the universe (seeding for galaxy formation, large-scale homogeneity.) This mechanism can be easily accomodated into the dynamics of the vacuum in quantum field theory. You have to have the vacuum "sit" in some kind of scalar background (the inflaton field.) The unfortunate aspect of it is that you must make all kinds of arbitrary assumptions about this scalar (pure-number valued, not changing under rotations) field.- Gravitational Potential Energy in a 2 dimensional Universe

Agreed. If we adopt the basic assumption that the equation for the gravitational potential be the topologically simplest assumption (no field lines start out from the vacuum), then Laplace's equation is the rotationally-invariant version of this assumption. From the initial assumption, gravitation can be deduced now. If we go to GR, as you said, it's a different matter. I do remember that the binding of a small particle coupled to a strong spherically-symmetric gravitational field has higher-order inverse powers of the distance than 1/r2. - How can information (Shannon) entropy decrease ?

Important Information

We have placed cookies on your device to help make this website better. You can adjust your cookie settings, otherwise we'll assume you're okay to continue.