Everything posted by tar

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Commanader, Yes, the divisions here are not meant to be Platonic solids with polyhedral faces. The divisions are actually drawn on the surface of a sphere. The geometry of the surface of a sphere is very interesting, as I discover more and more interesting characteristics of the spherical rhombic dodecahedreon, that Janus so nicely rendered for us, with the twelve identical solid sections, and all. (I am calling that solid shape you get when you cut along the lines of the spherical rhombic dodecadron to the center of the sphere, the Janus if it has not yet been named.) Thread, I am less concerned now that the diamond divisions are of inconsistent size. The line where the spacing between the great circle lines on opposite sides of the diamond is the greatest is the hexagonal plane line. These lines are actually skewed to the diamond in such a way as to give width to the edge divisions as well as the more central divisions, and the divisions are, after all, direct proportions of the four diamond border lines, which we have already determined, are of equal length. Found out a tentative answer to my earlier question of whether the length of the edge of one of the twelve sections was 1/6th of a circumference or was actually exactly a radius. While those two possibilities might not be the only ones, it appears, by crude measurement, that the lines are each a radius long. Using an engineering ruler with 60 divisions per inch I walked the ruler around the great circle of one of my spheres and found it to be about 370 divisions. Roughly measuring the diameter, holding the ruler behind the sphere it looked around 118 divisions. Dividing the 370 by Pi would get me a radius of 58.9 or so, dividing the circumference by 6 would be about 61.6. So I drew out my diamonds and measured the length of the 24 lines, adding them up and divided by 24 and got 58.58. This was closer to the 58.9 then to the 61.6, so I am proceeding as if the length of the lines is exactly one radius, until I prove, or it is proved otherwise. Subsequently I cut toothpicks into 118 division lengths and found I could lay out the figure (the spherical rhombic dodecahedron) laying a 118 toothpick(one D) down in its on track, making a cross with another 118 and repeating this procedure the six places on the figure where the 4-points are. Works out exactly. The six places being the North and South Poles, and the four equatorial cross points described earlier. Even more interesting was this tetrahedral figure, shown with just one toothpick at each of the six cross points. Regards, TAR The figure was made by placing on 118 D toothpick on each of the cross points and cutting off the four pieces of the sphere that stuck out beyond the subsequent tetrahedron, and then turning each of the toothpicks 90 degrees to represent the other diameter at the cross. Interestingly enough, unless I am wrong, it is exactly one diameter, along the surface of the sphere from one vertex of this tetrahedron like figure to the next vertex. You will notice the six toothpicks arranged like this, orthogonically to the missing six form a dual tetrahedron to the one the other missing 6 would form. It appears that the diameter of the sphere thusly laid out on surface, exactly meters out the surface into the spherical rhomic dodecahedron. Neat.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

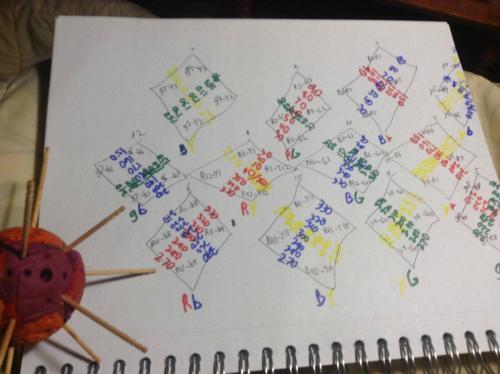

Might have a problem. The lines that divide the diamond into TAR degree diamonds may not be consistent. We already know that the two divisions per 1/12 of a sphere diamonds at the three points are shield shaped and not diamond shape. This was OK in my book, because as you divided into minutes and seconds the shield shape would be smaller and smaller and less of a percentage of the total diamond and would probably not interfer to badly with most mapping applications of the figure. However, there might be a difference in the size of the division diamonds, comparing central divisions with toward the edges divisions. Not sure yet, since this figure is surprising, but according to the trial pictured in this post, the dividing lines are great circles around the sphere. As you can see the dividing lines if extended around the sphere, intersect at the poles, form the same exact divisions on the diametrically opposed diamond (not shown). Looking at the spacing between these great circle lines, it reduces to 0 at the poles. This would seem to mean that the spacing would increase to maximum exactly half way between the poles, which would correspond to the center of the 1/12 diamond outlined with toothpick holes. This in turn would mean that the spacing closer to the diamond edges would be less, making the division diamonds, not consistent in size. Not sure yet, because the divisions seem regular, and propotional and the figure is based on the cube octahedron which has those "vector equilibrium" characteristics, but I am doing some thinking and trials and measurements on this, to determine the consistency or inconsistency of the size of the division diamonds. Regards, TAR Actually I misspoke. They are pen tip holes, not toothpick holes. The lines a drawn by moving a steak knife against the sphere in its own track, without a cutting motion attempting to keep the knife blade normal to the center of the sphere. The hexagona plane lines are made laying a toothpick against the sphere, in its own track.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

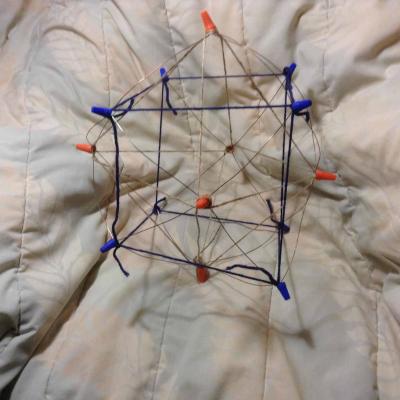

Thread, Interesting observation this morning. The cube octahedron that started this investigation popped back up when describing the four hexagonal planes. In the figure here (rotated 90 degrees CW to orient to diamond number one, the RY diamond conceptually) the toothpicks are normal to each of the four hexagonal planes, describing four axis. The toothpicks are at the eight "threepoints" of the spherical rhombic dodecahedron. This configuration (my observation) is exactly the same orientation as if you stuck a toothpick in each of the eight corners of a cube. Holding one of said axis and spinning figure your center passes through each of the six balls that are positioned at the center of each of the diamonds. These correspond to the center of the six edges of a cube that are not the six edges that your axis toothpicks are stuck into the ends of. Exactly. Interesting figure.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

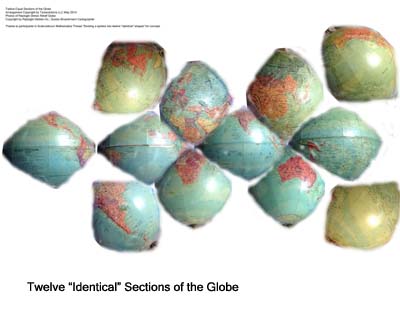

Here is more carefully drawn pingpong ball, with the lines depicting 10 degree divisions as opposed to the 15 degrees shown just before. Also arranged in same pattern as previous drawing of the 12 sections laid out to be seen at once, for better visualization.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Scheme drawn on pingpong ball. Same ball, five different shots, sort of following the red hexagonal plane around.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

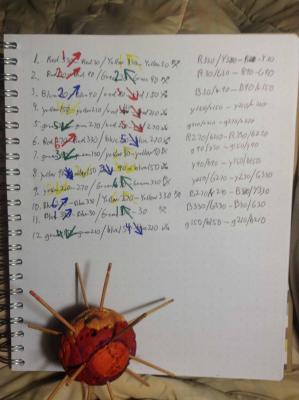

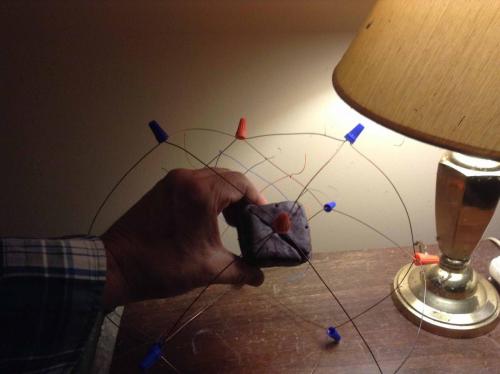

Been trying to come up with a way to depict any direction using the 12 segments (spherical rhombic dodecahedron shapes) and finally did yesterday, after making a realization the night before. I had a clay ball with long toothpicks at tje eight corners of the cube(blue wirenuts in previous picure) and short tootpicks at the points of the octahedron(orange wirenuts). I scored the ball between the toothpicks to make the 12 spherical rhombic dodecahedron shapes. I put a large penhole in the center of each shape. Then I noticed (again) that the holes lined up in the 4 hexagonal planes we talked about. I placed small penholes every 10 degrees and looked at the relationship the holes had to the grid when you divide the shape in quarters by drawing a line parallel and inbetween the sides of the shape. I noticed the angle was off, but it was off consistently, with the diamonds facing one way then the other. If i made 20 degree marks in the hexagonal plane I could use those marks to draw my parallel grid. Each diamond was thusly dividable into "degrees" "minutes" "seconds" and fractions of seconds if you wished. Any point on the sphere could be named, exactly and reproducably, as long as you had a naming convention, which I developed yesterday, by starting with the center of an equatorial diamond and going up and to the right, around the hexagon, and then the other hexagonal plane that goes through that point, up and to the left and all the way round. 6 60degree sections adding up to 360 degrees. Then I moved over on diamond on the equator and repeated the process. Each of the four planes has its own letter/color, and I used a Capital Letter to signify having the degrees increase upward and a little letter having the degrees increase downward. Thusly each diamond has its own name and numbering convention and is related to actual degrees. The lines (degrees) on my grid are a little shorter than the actual degrees so there are more square TAR degrees than actual square degrees on the sphere. TAR degrees come to 43200 square degrees (60x60x12) Actual square degrees in sphere are 41253 (approx) but the conversion from TAR square degrees to actual square degrees is regular and acurate. 1.0471 times 41253 is 43200 and of course the reciprical .9549 times 43200 is 41253. 1.0471 is 1/3 Pi. so the scheme is usable and convertable. And a whole lot easier than the figuring you have to do using spherical coordinants. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Imatfaal, I think what I am working on, is a directional, geometrical understanding of the universe. A scheme that gives permanent structure and relationship to all elements of the cosmos. The division of a sphere or a cube or an octahedron into the same 12 angular spaces can be like wise projected outward from a center point indefinitely and can be "done" starting from any point in space and time. Such a three dimensional scheme is already in place with our degrees of ascension and declination, but it uses the observer's and the Earth's reference points as the basis of measurement, which does not "nail down" the scheme and tie it to the greater universe. I have wanted, from my late teens, to be able to know, whether day or night, which direction I was heading in, in reference to the center of the galaxy. To be able to close my eyes and imagine the Earth's spin around it's axis, its revolution around the Sun, and the Sun's tilt and progression around the center of the galaxy...all at once. In one "picture", based on where it was I was sitting/standing/lying on the surface of the Earth. ...The other night, I was looking at the moon and imagining its progression Eastward around the Earth as it was heading to set in the West, and linked the Earth/Moon combine in its progression around the Sun, to a "picture" of the position and tilt of the Earth and its progression around the Sun, to such a picture I had formulated around the same time of year 30 some years ago in Germany. I think my crazyman drawing of the 12 diamond shapes onto the world, from my deck over the summer, has increased my geometrical understanding of the place... and brought me one step closer to being able to see the whole arrangement, at once. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Imatfaal, Talk to you later. Once I figure out what I am working on. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Don't know what it means yet, but made an octahedron from clay, stuck a toothpick in each apex and in the center of each face, for reference, and cut out the diamond shapes by making cuts between the toothpicks. Exactly twelve, with exactly the same internal angles as cutting the sphere and the cube into the twelve sections. The "edge" was exactly 90 degrees off from the cube segments but you could switch one segment from the cube of the same far corner to corner size as a thusly cut up octahedron of the same far apex to apex size. Have not figured out exactly how that ties back to the figure (the spherical rhombic dodecahedron) but I thought it worth mentioning that the octahedron was exactly setup anglewise to be sectioned in the same twelve internal angle sections. And of course the twelve edges, and the being a dual of the cube, helps.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Imatfaal, Well wait. I did understand what you were saying in the link about the cubic octahedron being the dual of the rhombic dodecahedron. What I noticed the other day was that a pure string colored octahedron, with eight triangular faces was inside the figure, with each face exactly oriented to a vertex of the purple cube. And vice-a-versa. Each face of the cube was exactly oriented to a vertex of the octahedron. The octahedron has eight faces and 6 vertices. The cube has 6 faces and eight vertices. And each has 12 edges. The middle of an edge of the cube is exactly on the same ray from the center of the complex as the center of an edge of the octahedron (although the edges do not intersect at a point, just intersect the same ray from the center of the complex, which incidently is on the same line as the ray projecting 180 degrees the other way, through the center points of the opposite edges of both the cube and the octahedron.) Although ultimately, the meaning of cubic octahedron and the meaning of a cube and an octahedron, might be the same after inspection, there are some distinctions and some interesting relatiions intertwined in the distinctions. Most interesting to me about this, is the fact that the diagonals of the diamonds, when inspecting the spherical rhomic dodecahedron do no touch, and the edges of the cube are "outside" the edges of the octahedron. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Imatfaal, Right you are. I read the words but didn't see what you meant, 'till the other day. But then again, I am 60. I meet new people all the time. And have new ideas all the time. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

The center of each diamond shape can be seen as the intersection of one of the string colored "edges" of the octahedron, behind one of the blue colored "edges" of the cube.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Another neat observation about the spherical rhombic dodecahedron made with wire and wire nuts. If you join the blue wire nuts each to the three closest other blues with string, you get a perfect cube. If you join the orange wire nuts each to the four closest other orange with string, you get a perfect octagon. Regards, TAR I have only done it the one way, then the other. I will get some colored yarn and do both and take a picture, later today, after work. Its pretty neat. My edit is not working, I meant octahedron, not octagon.

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

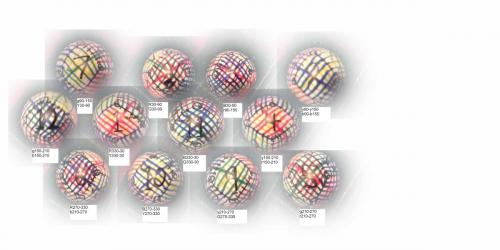

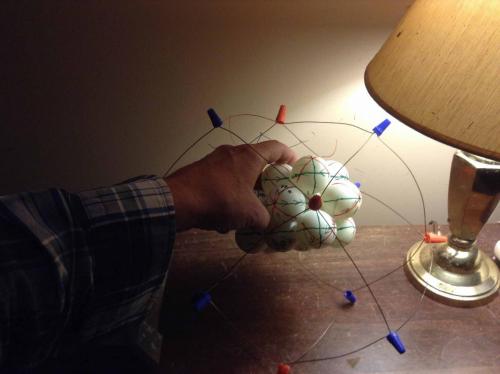

Addendum, Built a Spherical Rhombic Dodecahedron out of 24 pieces of wire of equal length, 6 orange wire nuts and 8 blue wire nuts. The orange wire nuts are on the "four points" analogous to the center of each of the six sides of a cube. The blue wire nuts are on the "three points" analogous to the 8 corners of a cube. Another image to take is that of a globe with an orange nut at the North Pole, one at the South and the other four equally spaced around the equator. Each of the blue then, four in the northern hemisphere and four in the southern are placed exactly in the middle of the polar orange and two of the equatorial ones. Attached are a picture of the SRD with the 12 sectioned cube pictured earlier in the center, oriented with the center of each face aligned with an orange nut, and each corner aligned with a blue, and a picture of the SRD with the close packed arragement of twelve balls around a center ball (ignore the extras), with each of the 12 balls, aligned with the center of one of the 12 diamond shapes of the Spherical Rhombic Dodecahedron. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, Made a string version of shape with the 12 diamonds we are talking about here. Then blew a balloon up, inside it and drew with marker on the balloon, dividing each diamond into 4 to get 48 sections, then divided each of those diamonds in quarters to make the 192 sections. (and then once more to make the 768 What was interesting was that the shield shape we got dividing each diamond into four, "stayed in the 120 degree corner. That is a diamond divided into 4 had two shield shapes a diamond divided into 16 had 2 shield shapes and the diamond with 64 sections had only two as well in the 120 degree corner. Led me to think that any continuing division would always have 24 of the sections shield shape, and the rest, exactly the same symetrical diamond shape. With enough divisions the 24 would become tiny areas, eight of them, analogous to the corners of a cube, and with enough divisions, just the imaginary "points" of the corners of cubes. Still seems to me we can make something of this way of dividing the cube, or the sphere. Any amount of pixels in that 12, 48, 192, 768 ... sequence could be used to define solid space around a point where each of the pixels minus the 24 shield shaped ones, were exactly the same size and shape, and in a definite, known position. Regards, TAR Thread recap. Take a cube. Cut off the corners to the midpoints of the edges and you have a cuboctahedron. Put the center point of twelve balls on the 12 vertices of a cuboctahedron and you have a close pack situation with 4 intersecting hexogonal plane orientations and a rather neat situation. Put a dot on a sphere in the exact location of each of the twelve balls an draw lines halfway between the points and you wind up with the twelve sections of the sphere or the dual of the cuboctahedron, the spherical rhombic dodecahedron, that Janus rendered so nicely. Draw the cube on the sphere and the sphere on the cube, using this scheme and you have the twelve sections of the sphere, all identical shapes with internal angles of 90 and 120 degrees. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

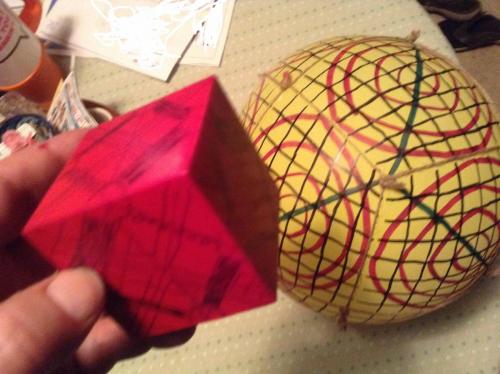

Acme, Have not gotten the trig down yet. But am still working the problem. Figured out on Thursday how the diamonds relate to the cube. Drew the diamonds onto the cube. The 8 three points are the corners of the cube, and the 6 four points are located right in the center of the faces of the cube. The center of each edge is the location of one of the 12 balls that fit exactly around a center ball of the same diameter. Each midpoint of an edge is the center of a diamond. Relating a cube to the 12 sections of the globe, the top of the cube would have the top half of 4 diamonds, and each of the bottom halfs of those four diamonds would be on one of the sides of the cube, being the triangle you get when you draw an x corner to corner on each side. The diamonds are thusly "folded" in half by the edge. The long axis of the diamond goes from center of top to center of side, and the short axis of the diamond goes from corner to corner. Works out exactly, internal anglewise. I made two clay figures, a sphere and a cube. Sized them, so the distance from center of cube to middle of edge was approximately the same distance as a radius of the sphere. Then I cut the sphere into the 12 sections, and cut the cube into the same 12 sections, with the same internal angles, so that you could replace a peice of the cube with a peice of the sphere and vice a versa. Pretty neat. Looks like this. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Thank you Acme I read the wiki article, still not sure how to work my problem, when to be in degrees or radians or rads, and I am not sure what angles and distances I "have" already, when I can use an identity, and when I can "figure". But I suppose if trig is what I need, trig is what I need to remember and work with. Got my sister's advanced high school math book out, and will see if I can figure it out. Thank you for the direction though. It is obvious that trig is what I need to be understanding, to do the problem. Have run into sine and cosine and tangent and cotangent before, as I actually did take trig in high school, but I think I was more interested in girls and drinking and smoking, and having fun, than in understanding the implications and uses of the log tables and tables of the trigonimetric functions and the like. I liked them then, and I actually had fun looking at the tables in the back of my sister's book, looking for the patterns. So, as no one else yet has given me a yes or a no as to the exact length of the side of the diamond on the spheroid, I suppose I will have to figure it out myself...using the trig you have pointed me to. Might take a while...but if no one else gets back with the answer, I will eventually. Regards, TAR But, this being a math forum, I would not mind any help anyone would like to give, in setting up the problem and properly executing the math. My thinking is that I have three angles of the triangle made when you run a great circle through though the center of the diamond from obtuse point to obtuse point. The acute point is already a known 90 degree angle, the obtuse point is already a known 120 degree angle and half that would be 60, so the angles are 60, 60 and 90. From this, according to the wiki article, I think I have 3 out of 6 unknowns know, and think I might be able to get the other three from it. If not, if I need an arc length, I could, I suppose, assume that my two arcs of the triangle, that are also arcs of the diamond, are exactly 1, and thusly "find" the length of arc that goes from obtuse point to obtuse point, as that I would have 5 out of 6 to plug into the identities. Then whatever answer I get for the length of arc from obtuse point to obtuse point, I can plug back into the identities, knowing the three angles, treat the other two identical arcs as unknowns, and see if they turn out to be 1. If they do, then they are 1. If some other number comes up, then they are not 1. That is the plan, I am not confident though, in my ability to execute it, and will gladly accept any help, suggestions, directions, encouragement, or correction. According to my sister's math book, the sine of 90 derees is .0000 the tangent is .0000 and the cosine is 1.000. The Cotangent seems to be ------, which I am not sure means either infinity or undetermined. 60 degrees in the chart shows sine=.5000, Tangent-.5774, Cotangent=1.7321 and Cosine=.8660. Addition information, given by the chart is that a 60 degree angle is equivalent to 1.0472 radians and a 90 degree angle is equivalent to 1.5708 radians. In support of my thought, that Pi must reside in these angles, I just this minute made the interesting observation/calculation that 1.0472 is 1/3 of Pi. (not surprising as that 60 is one sixth of 360 and a radius is 1/2 a diameter,) but interesting, none the less. But still to figure or to understand, for me, is when you can use a radian as a length, and when you can use it as an angle, whether the length of the arc is exactly r, or 1.0472 r, or .9549r...or indeed some other length. It "looks" to be around r somewhere, as that one can tape up a 12" globe with approximately 6 inch pieces of tape, into the diamond arrangement, using the poles and the equator as guides. Which is more likely to be correct, that the arc length is exactly r, the arc length is exactly 1/3 pi, or that the length is some other number? No doubt I can assume that 1.5708 is likewise 1/4 Pi without doing the math (using the calculator.)

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Unity+, The way to find the length of the circle segment that corresponds with the sides of the diamonds. Earlier I think it was MD65536 that let me know the angles of the diamonds, but that was the polyhedron, "flat" diamond shape. I am more, at this point interested in the length of the arc from corner to corner, measured along the surface of the sphere, not the straight line that would go "subsurface" between the points. Regards, TAR Imatfaal, Sorry, I misidentified the provider of the angles. It was you. "Ratio of long diagonal to short is sqrt(2) (this is for the flat edged polyhedron not for the spheroid). If the short diagonal is 2 units long, the long diagonal is 2.sqrt(2), and very happily the length of the side is sqrt(3). The small angle is 70.53 degrees." Unity+, So anyway, knowing that as a plane the diamond shape has the above angles, and as a sphere section the obtuse angles seem to join at 120 degrees if you think of a plane tangent to the sphere at every 3-point in question, and the acute angles seem to be 90 degrees if you look at the 4-point junctions, from the perspective of a plane tangent to the sphere at a 4-point. I am interested in what makes a 109.47 degree angle a 120 angle and a 70.53 degree angle a 90 degree one. And I am interested in learning how one deals with angles when they are on the surface of a sphere, and not on a plane. Primarily to figure out if the diamonds that you get when you cut a big 1/12th of a sphere diamond into 4 similar diamonds, are the same 70.53 angle when looked at, as if they are transribed onto a plane inside the sphere, or if they retain any of the 90 degree, 4-point type characteristics when being on the surface of the sphere. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Here is another arrangement, of the same 12 sections, showing the four Northern "polar" divisions, the four equatorial divisions, and the four Southern "polar" divisions. Still would like to know, if anyone can do the math, if the sides of the diamonds are exactly r or not. (When measured on the surface of the sphere.) Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Acme, I am sixty. I probably saw Fuller's projection in the 60s. It most likely was one of the reasons why I was investigating the divisions of a sphere, with my clay balls and such. Because I wanted to better visualize a sphere, and understand solid angles and such. The division into 12 segments I presented at the beginning of the thread is not new to the world, but it was new to me. I learned the names and such of these figures in this thread. But the concepts and the "neatness" of the arrangement, were things I noticed myself. Obviously the characteristics of a sphere, are not my invention. I am just noticing stuff about it, and talking about it on a mathematics board. Perhaps it will interest someone, perhaps it won't. I do not have the understanding of solid geometry and calculus it would take to figure if the length of the diamond's side is exactly r, when measured on the surface of the sphere, but it would be "neat" if it was, and would have implications as to what Pi is. That is, as to "why" Pi is. Just one of the things I care about figuring out. If it has already been figured out fine, I am just looking for the answer, one way or the other. Can anyone help me, in this regard? The figure Janus modeled is already known. Is it known what the length of the arc, describing one side of the "diamond", as measured on the surface of the sphere, is? Regards, TAR MD65536, Thanks for the link, and the suggestions. You are right, I could pick better continent preserving starting points, but I liked the idea of using the North and South Poles as vertices. And the four lines coming from the poles seemed rather regular and understandable, so I put them on the prime meridian, and the 180 "date line" area, and let everything else fall where ever it fell. My thinking on this is that the Rhombic dodecahedron projected onto the sphere, is more important than the sphere projected onto the Rhombic dodecahedron. This is why I am considering that my rendering is not a projection, but twelve pictures taken of the actual curved surfaces, and laid out in a way that you can see the whole sphere at once. Perhaps it is not very useful as a map, but more as a "visualization", being able to "see" all sides of the globe at once. I always had trouble with the projections. Not that they were not mathematically correct, but that they distorted the place, and I didn't know how to make the corrections. We are used to making the corrections required when we look at a ball, so why not keep it a ball. The twelve divisions I think is a nice balance, sort of vector equalibrium, of the place, that gives one the "idea" of what curvature is about. Was standing out on my deck today, probably looked like a crazy man, drawing lines in the air, dividing the world into these diamonds, with the four "equatorial" diamonds, and the four polar diamonds and the four diamonds below, using my neck/head/eyes as the center point. Seems really neat and clean, how the "90 degree" juntures and the "120 degree" junctures work out, to "form" the sphere. And one can divide the 3D world using these 12 identical diamonds. I think it has possibilities. We could call the center of the Milkyway the "below" 4-point, and the opposing point in the sky the "above" 4-point, choose something that was on the resulting "equator" as a 4-point, and that would determine the other three 4-points. The 3-points would also all be thusly defined. Then the Celestial Sphere would be divided in 12 equal areas and each of these areas could be divided in quarters (from mid edge to mid edge, not point to point), and each of those quarters into quarters, as many times as would be useful. And each subdivision would be exactly defined in both solid angle, and direction. Most celestial objects would keep their designated position for thousands of years, and if we picked a very far away galaxy as our equatorial starting 4-point, we would have a "wireframe" with-in which to measure and chart every object and motion within it, against. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Acme, No doubt I could have gotten the idea from Mr. Fuller, but I also got it from suggestions on this thread, and I have not copied Mr. Fuller's projection onto the cuboctohedron. I do not even recall ever seeing his projection onto a cuboctohedron. The icosahedron pictured in the link, is not the division into twelve equal segments we are talking about here. We are talking about the one Janus modeled. The cuboctohedron is obviously the figure upon which the diamond segments are built, as that each of the diamond shape's center's are located exactly on a vertex of the cubooctohedron, but the diamond shape, we have already determined is not condusive to making a hedron out of, as the four points of the diamond are not on the same plane. However, retaining the curved surface of the segment, results in no projection onto a flat surface required. The idea is therefore similar to, but not exactly the projection of Fuller. And although it is built on the form of a cubooctohedron, it is NOT a projection of the features of the Earth onto the flat surfaces of a cuboctohedron, and does not use at all the icosahedron, nor does it unfold well, nor is it "flat", except it is a photo on a two D surface. There remains some interesting attributes of the figure that can be explored. Perhaps you can help, or someone can help with establishing the truth or falseness of a conjecture I have related to the figure Janus modeled, and the division of the globe, I have presented here. The globe I used, was a 12" globe. (12" in diameter). I built the sloppy divisions, using peices of tape, 6 inches long. This appeared to me, to work out exactly. Leading me to make the conjecture that the distance between the corners of the diamonds, when measured along the surface of the sphere (as in a peice of tape or a string that could lay flat on the sphere) was "exactly" r. Does anyone know spherical geometry well enough to calculate the length of string or tape it would take to make the edges of the diamonds on the surface of the sphere? It already seems to me that the lengths are identical, but are the lengths equal to r? Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

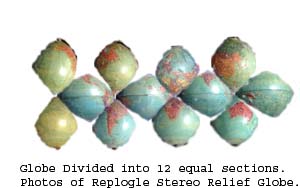

Here is a crudely done rendition of the globe divided into the same twelve "identical" shapes. The globe photographed from twelve vantage points is a copyrighted Replogle Stereo Relief Globe, by RePlogle Globes Inc., Gustav Brueckmann, Cartographer, with polical boundries and names as they existed 50 or 60 years ago. Used without permission. Rendition executed to see what the world would look like, from 12 directions at once, on a two dimensional space, using the segments we have been talking about. There is no projection involved, all continents are "actual" size, to the same scale, as each of the photos is taken of the same 12" globe, from approximately the same distance. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Mike, Thanks for the quick bio. Important for me to remember, when I notice stuff about the world, that its been looked at before, and thought about before. Also important, I think, for the young folk coming up to remember that some of the things in the world that they take for granted came from somebody's ideas and work bringing the ideas into reality. Sure we have fantastic systems and tremendous knowledge at our finger tips, but somebody was programming Commodore 64's and bringing digital copiers into the business world, and designing pedal powered electrical storage and such, that laid some of the groundwork, for what we have now. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Imatfaal, That 70.53 I am thinking is important, the obtuse angle of course is then 109.47, because the four angles of the flat diamond would have to add to 360. But we have already decided that the diamond is not flat, or not flat yet. Those angles are taken on the projection of the rays eminating from the center of the sphere, as to where they cut the plane that is normal to the sphere and touching the center of the diamond. What is interesting to note, is that the obtuse angle, when measured on a plane, normal to the sphere, at the vertex or junction is actually 120 and the 70.53 is actually a 90 degree angle at the vertex. So the function, I was talking about earlier might be the one that takes 120 to 109.47 in the limit, and takes 90 to 70.53. I am thinking this will work, because when you divide the diamond in half side to side and not vertex to vertex you keep the same diamond proportions on all 4 diamonds you thusly create from the one. And each of these diamonds can similarly be divided in perfect four, retaining the diamond proportion. As the diamond shape gets smaller, it also gets flatter, never getting completely flat, but necessarily approaching the 109.47 to 70.53 angle. Since the curved sphere sees the angles as 120 and 90, and the "flat" side sees the same angles as 109.47 and 70.53, pi should be in there somewhere. Regards, TAR

-

Dividing a sphere into twelve "identical" shapes.

Janus, Wow, I was looking at your triangle ball with the nice complementary colors. I was noticing the eight (twelve rather) circles cutting through...and thought you had just sliced the aphere in half and then half again, and so on, from three different angles...then I saw you had taken the 12 diamonds and split them on the diagnonals. Interesting figure we are working with here. Certainly dual, if not quad or something. Interesting indeed. Regards, TAR Mike, Once they do another round of satellite photos, I will look for the great white mike smudge on Grand Canary. Regards, TAR