-

Posts

11785 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

4

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by Cap'n Refsmmat

-

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

Er. "Events happening right now are simultaneous no matter what." "Okay, here's an example where changing reference frames causes events to no longer be simultaneous." "Makes perfect sense. Nevertheless, events happening right now are simultaneous no matter what." Perhaps you should elaborate further on the evidence for your claim. I'm not particularly impressed by your own contrived example, since it's easy to create an example that follows your rules, not relativity's. -

Reputation versus time

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to michel123456's topic in Suggestions, Comments and Support

It's quite possible. Also, since the reputation points displayed on your profile are cumulative, you have a natural advantage from having more posts. Some sort of reputation/post ratio, like you did above, would be less misleading. One could also hide the reputation display on individual posts, just leaving the +/- buttons, so you can thank the member without everyone knowing and following your lead. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

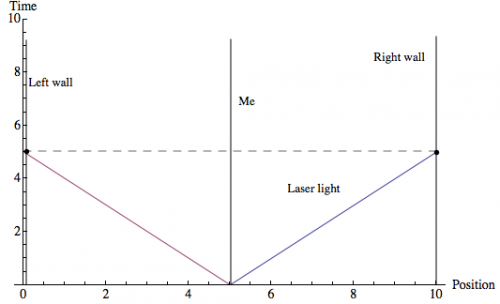

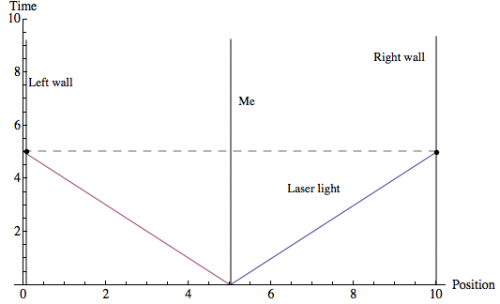

If the speed of light were not constant in all reference frames, we would find that the light strikes the walls simultaneously in all reference frames: Here you see the light moving at different speeds, since it's launched on a moving train; the light in the direction of travel goes faster, and the light intersects the walls simultaneously. This is what we'd see with bullets or model airplanes. Light, however, behaves differently, as you could see in the diagram where the light reaches the wall at different times. This is solely because of its constant speed in all reference frames. The constant speed of light necessarily means that certain events can change order -- i.e., one that appears first in one reference frame can appear second in another. After all, I could draw the train moving in the other direction (or observe the train from a car driving past it very fast) and see the light reach the left wall first, rather than the right. The interesting thing about this is that causality is always conserved; reordering events cannot create paradoxes. There is a difference between "I saw the explosion as happening eight minutes later, since the explosion was very far away and the light didn't reach me" and "the events are no longer simultaneous, even when I compensate for the light delay." -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

You are still conflating light delay (the time it takes for us to see things) with relativity of simultaneity. The eight-minute delay in the travel of light from the Sun to the Earth has absolutely nothing to do with relativity of simultaneity as presented in special relativity. In my example, what is happening in the railcar depends exactly upon whether you're moving relative to it. Your dictum has been to measure events in the frame in which they are at rest -- e.g. events are simultaneous when you're standing on the railcar, in its reference frame, so they must remain simultaneous. What if the two walls of the car are moving in different directions? How do you decide which reference frame is correct? -

So if nobody has confirmed it, why are you so sure? How did you get the idea in the first place?

-

You may also be able to use your SSH credentials in a program like CyberDuck or Transmit to connect to the server with SFTP or SCP, then transfer files in the GUI.

-

Traveling at the speed of light paradox?

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to questionposter's topic in Relativity

It's length contraction that occurs, and it does happen in particle accelerators; the particles or atoms being accelerated to high speed seem to "flatten" into thin pancakes. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

Yes, it does. Take a look at both of the diagrams I gave again: the one for the observer on the train and the one for the observer on the side of the tracks. In each case, the light travels a unit of distance in a unit of time -- it does not change speed. What changes between reference frames is the relative velocity of the railcar. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

Something to that effect has been tried: http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/Relativity/SR/experiments.html#round-trip_tests The beat frequency gives the difference in frequency between lasers; as they changed the orientation of the rotating laser, any Doppler shifting would cause the beat frequency to change. It did not. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

Hm. I swear I replied to this... You're conflating reference frames. Keep in mind that there's multiple reference frames possible: we could observe this situation from a car driving past, for instance, or from an airplane. Each will see a different velocity of the railcar, and one can't say there's one definite railcar velocity. It depends: velocity relative to what? Any detector or observer on the railcar will measure it to be standing still, because it is not moving with respect to him. A detector on the railcar won't measure a Doppler shift in the light. A detector used by an observer in a racecar driving past will notice a pronounced Doppler shift, and a detector used by the couple picnicking in the park next to the tracks will notice a lesser Doppler shift. There's no way for the observer on the car to measure the car at anything but rest, since the car is indeed at rest with respect to him. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

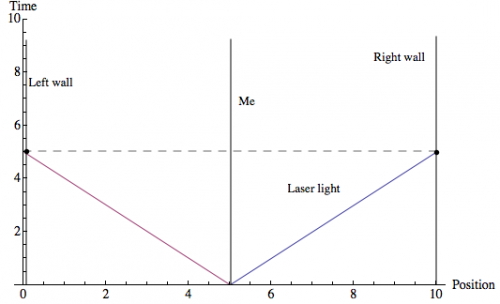

The speed of light is measured to be the same no matter where you are, how fast you're going, or what reference frame you're in. You were exactly right up until you concluded the person inside the railcar would observe that the room is moving. The person inside the railcar observes this version of events: ...since from his perspective, the railcar is not moving relative to him. It's only the person on the side of the tracks that would observe a difference in times, caused by exactly the mechanism you explained. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

Your position is also irrelevant in this diagram: Notice the very specific lack of a "You Are Here" arrow. Where you stand along the tracks will not change the diagram or the outcome of the experiment -- it will merely shift everything uniformly left or right. In very explicit words: If the wall is moving towards the light, the light will reach the wall sooner. If the wall is not moving towards the light, the light will reach the wall later. In different reference frames, the light never changes speed; the wall does. Is that not clear? You don't seem to understand what the assertions of relativity even mean. Disagreeing with them is another matter entirely. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

I don't think you understand; signal delay -- the delay in "seeing the happening" -- is not relevant to my example. It is not even included in my example diagrams. The diagrams show the light moving and intersecting with the walls; they do not show the time it would take for light to travel back from the walls to the observer. The difference in times on the moving railcar is due to the motion and the constant speed of light, not due to the time it takes for me to realize the light has reached the walls. Please review the diagrams and let me know if you have any questions. I will get to this once the basics are clear. At this point, addressing your question is premature, since you don't yet seem to grasp the fundamentals of relativity. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

I'm giving a concrete example of the relativity of simultaneity, not length contraction. The aim is to show that two events (the light hitting the walls) occur simultaneously from one perspective (mine) but not simultaneously from another perspective (yours, standing next to the tracks). Is that not clear? -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

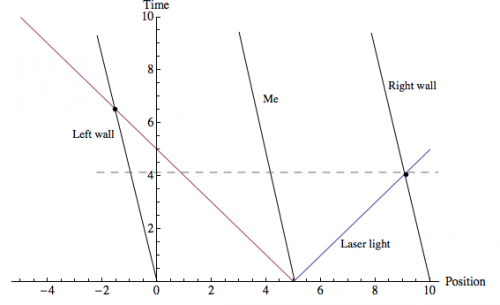

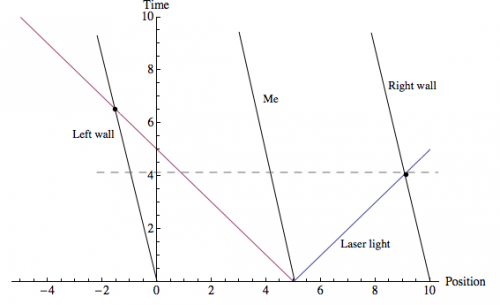

Hang on. The light is moving at exactly the same speed in both diagrams. It's not getting any help from the railroad car. Take a look. Here, the light takes five units of time to travel five meters: Here, the light also travels five meters in five units of time: It's just that the train moves while it does so. The speed of light hasn't changed at all! The slopes (distance traveled / time taken) of the light lines are exactly the same, indicating they travel the same distance in the same amount of time. I explicitly drew the light not getting any help from the railroad car. If the diagrams appear incorrect to you, perhaps you could suggest corrections or adjustments. Well of course. I'm not trying to prove length contraction yet. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

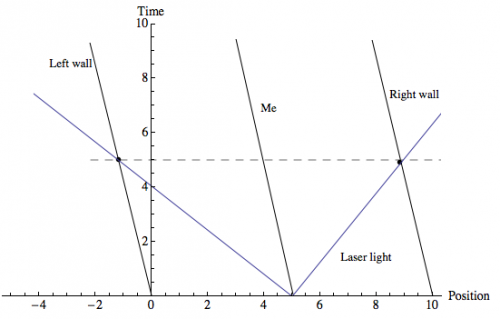

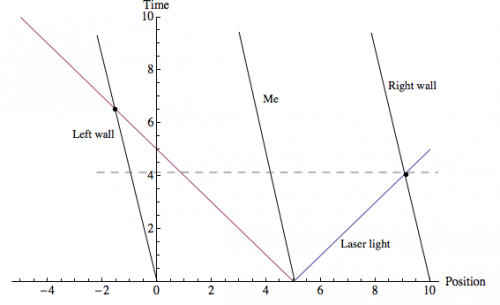

Roughly the same idea. We must simply take into account the time of observations. I think we agree. Righto. Let us suppose that my room is actually on a railroad car moving down the tracks, and you're watching. You watch to see the path of the light and the path of me, over time: I'm on a railroad car moving to the left, as you can see. The walls move as well, because they're attached to the railroad car. The light emitted by my laser travels at the speed of light and hits the walls. One light pulse hits just after four units of time, the other just after six. Had you seen the speed of light change between reference frames -- just like my speed is 0 in my frame and nonzero in yours -- it would all match up, and the light pulses would hit at the same times. Unfortunately, the speed of light is constant for everyone. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

As I said: An "event" is an object being in a specific place at a specific time. Events have not just a location but a time. An event might be an explosion, for example, which occurs at a specific place and only at one very specific time. An object exists over a length of time, and hence consists of many separate events. If I measure the Sun's position right now, that is a single event. Its position four hours from now is a separate event. Those two events are four hours apart in time. Just like if I blow something up now, then blow it up again tomorrow, there's a time between those two events, even though it's the same thing I'm blowing up. Righto. Imagine this situation: I am standing in the middle of a large room, ten meters wide, exactly between two walls. I have two laser pointers which I point at the opposite walls and fire simultaneously. The light from each laser pointer travels five meters to the wall and hits it. This is the diagram showing the situation: Position is in meters. I'm measuring time in funky units, such that light travels one meter in one unit of time; the diagram is clearer that way. Clearly it takes five units of time for the light to reach the walls. I've marked the five-unit time with a dashed line so you can see the light reaches the walls simultaneously. Before I move on: is this situation clear and coherent? Does the diagram make sense? I don't want to jump in deep without being sure you understand. (edited for clarification and adjusted diagram) -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

[math]\Delta x[/math] is the spatial distance between two events which occur at the same time. (You wouldn't measure the distance between the Earth now and the Sun ten years from now.) Since simultaneity is relative (a logical consequence of the constant speed of light -- I can give a concrete example if you'd like), necessarily spatial distance is as well. But s is not relative. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

The "actual distance" is s, and no, it does not change with different observational frames. [math]\Delta x[/math] and [math]\Delta t[/math] might, though. -

Traveling at the speed of light paradox?

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to questionposter's topic in Relativity

Also, relativity is based on the postulate that light will always be observed to travel at the same speed by any observer, so if length contraction and time dilation caused anything else to occur, special relativity would be internally inconsistent. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

It would certainly be more fun, however. That works here. We don't need to invoke general relativity in this case, since adding gravity and spacetime curvature just makes things more complicated. An "event" is an object being in a specific place at a specific time. One could describe the Earth and the Sun as two separate events: "the Earth was in this place at exactly this time," and "the Sun was in this other place at exactly this time." (Clearly their positions change through time, so one must specify the time.) So if I measure the spatial distance between two events, I can call that [math]\Delta x[/math]. If I measure the time that elapsed between two events, I can call it [math]\Delta t[/math]. So suppose I measure the distance between the Earth and Sun right now. In the spacetime interval: [math]s^2 = (\Delta x)^2 - (c \Delta t)^2[/math] ...[math]\Delta t = 0[/math], since I'm measuring the two positions at exactly the same time. So the interval between those two events is [math]s^2 = (\Delta x)^2[/math], or just the distance between them right now. Now, suppose I measure Earth's position now and the Sun's position ten minutes from now. Now [math]\Delta t = 10\text{ s}[/math], and so the spacetime interval ends up different than before. That makes sense, because I'm measuring the Earth's position and the Sun's position at different times. Clearly the distance won't be the same. Now, everyone will agree on the spacetime interval between two events, no matter where they are, what they're doing, or how fast they're going. Even if the distance is contracted, the spacetime interval will come out the same. -

m represents the maxima, right? The first maxima on one side is m=1, the next maxima m=2, and so on. So if you want the experimental error of lambda at the first maxima, you use m=1. If you want the experimental error at the second maxima, you use m=2. And so on.

-

Does Progress Hamper The Economy Or Is It The Other Way Around?

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to Phi for All's topic in Politics

That's a fairly long-term strategy -- and in the short term, developing for higher efficiency makes their cars more expensive to purchase. And from the lightbulb debate we know that consumers consider up-front price before considering long-term cost of ownership. I also wonder if mileage driven and gas prices are linked as directly like that. When gas prices spiked in recent years, I seem to recall demand from drivers dropping only slightly. People tend to drive where they need to go, and it's difficult to alter their driving habits or destinations without major cost incentives. -

Does Progress Hamper The Economy Or Is It The Other Way Around?

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to Phi for All's topic in Politics

But for 50+ years of the last hundred, nobody thought efficiency or emissions were important goals. Gasoline was cheap and air pollution from other sources was a bigger problem. Power was the goal, and power is what they achieved in spades: the Model T had a 2.9-liter engine that made 20 horsepower, and a modern Taurus makes 260 horsepower from an engine only slightly larger. After the past couple decades of regulations, products where emissions matter the most (like heavy trucks) have experienced huge improvements. You should take a look at the state of patents in the software industry. Patents are used as offensive weapons rather than means to protect innovation, and some are worried that small businesses and entrepreneurs will stop innovating for fear of being attacked with a patent lawsuit. -

Frame of Reference as Subject in Subjective Idealism

Cap'n Refsmmat replied to owl's topic in General Philosophy

No. A spacetime interval can be calculated without the notion of spacetime existing: [math]s^2 = (\Delta x)^2 - (c \Delta t)^2[/math] This can be done only with knowledge of the speed of light, the distance separation between two events, and the time between those two events. One must not make any assumptions about the nature of spacetime; one could say that spacetime consists of tie-dyed rabbit pelt and spacetime intervals would work equally well. All one needs is the notion of a distance between events and a time between events. The ontology of spacetime is irrelevant to the invariance of the interval. Relativity predicts that any two observers will agree on the spacetime interval between events, no matter what reference frame they observe the events from. The spatial and temporal separations might differ between frames, but the interval does not, regardless of what "spacetime" is or isn't.