Everything posted by studiot

-

If I move a box with nothing in it, does the nothing move with it?

Yes I think you put your case quite well +1 and welcome here. Sadly I think you took your analysis to extremes and even contradicted yourself with your additional post. Apart from the fact that space, empty or otherwise was not mentioned by Kitty, you have told us a couple of times that you can't link 'contains' to 'nothing' and then gone and done just that in the last line! Try this. I have just one apple in my bag. I eat the apple. Now my bag contains nothing.

-

Safer for a healthy 32 year old: contracting COVID or getting the vaccine?

For those who think getting a blood clot from the vaccine is bad, here is what you could get with blood clots from the real thing. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-57569540

-

If I move a box with nothing in it, does the nothing move with it?

Agreed.

-

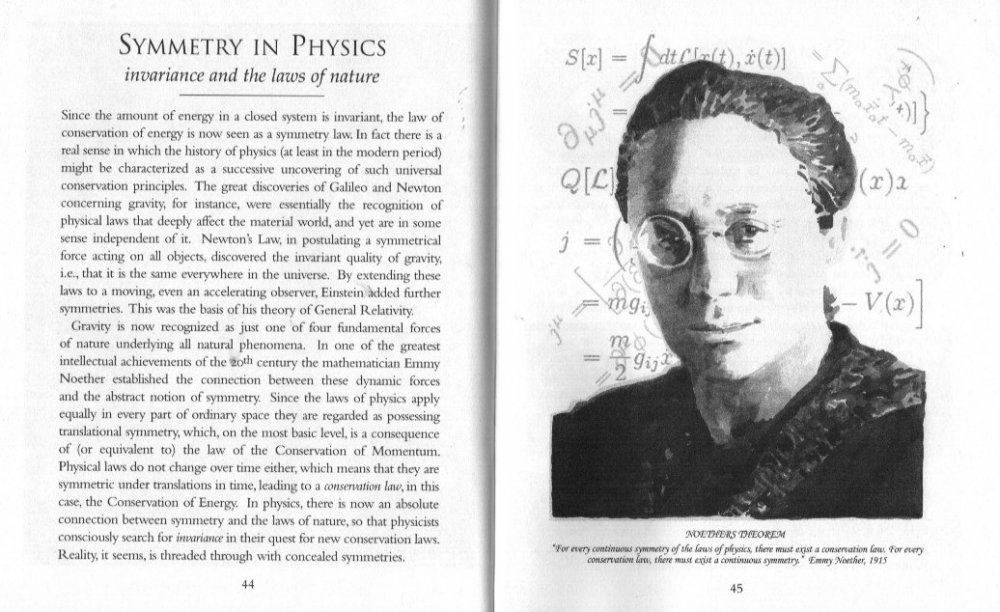

Noether's Theorem and dimensional analysis

A fine example of my point. "an experiment" is something other than space. A simpler example would be congruent triangles in euclidian geometry. Congruence is a symmetry that can be established by the conventional methods as taught in lower high school. But the whole of euclidian geometry can be recast in terms of transformations so that congruence becomes a translation (and perhaps a rotation) so that you can overlay one triangle on another. But you require something other than space alone, in this case two triangles, as I said.

-

If I move a box with nothing in it, does the nothing move with it?

But I didn't get an answer to the Physics content of my post. But I would go further than anyone else here and declare that a box which contains exactly nothing is impossible as a self contradiction. Let us say this 'box' has sides of 10 cm by10cm x 10cm that is it has a volume of exactly one litre. So it has the capacity to contain one litre of whisky. Now capacity is an abstract noun, to be sure and an old fashioned one to boot. But a noun it is and therefore a 'something' So by studiot's theorem "Every empty box contains something."

-

Noether's Theorem and dimensional analysis

Again swansont has hit the nail exactly on the head here. A carbon dioxide puck would be continually subliming away like crazy. So its mass would be continually diminishing. From the text of your original submission I wonder if you realise that 'space' alone does not admit of translation. Something translates or is translated in or through space (or rotates in it). And it is the invariance of some property of that something that provides the symmetry, not the space itself. Did you get your reference to Noether from somewhere like this ?

-

Collapse of a building...

It really is too early to tell with any confidence the mode of collapse. My impression of the structure was that it was in three parts. laid out like a letter H for stability. Often buildings of this type Either the wings are more strongly founded and constructed and the central joining leg spans between them. or The central joining leg is the most massive and strongest, and the wings less so. The point is from this sequence https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-57609620 The failure appears to have been a breaking of the connection to one side support starting the collapse of the central section, which then pulled the other side over with it. The upper levels of the centre appear to have broken and fallen at one side, onto lower levels which then collapsed in on themselves in the middle under the extra weight. There is a report that 15 years after the building was constructed (about 1995) it started settling or subsiding and has been doing so ever since. There is another report suggesting inadequate drainage leading either washout or excess (clled active) soil pressure on the basements. Either way if excessive differential settlement occurred and the centre lost sufficient of its support from one or both sides, collapse would occur rather as in the video. But proper investigation will reveal much more, I don't doubt.

-

Noether's Theorem and dimensional analysis

So tell us what expression of the theorem you have as it is difficult to offer generalisations if the question is too broad. Swansont has offered a good summary in his second post +1

-

If I move a box with nothing in it, does the nothing move with it?

What I don't understand is what this Physics question is doing in the General Philosophy question. A couple of hundred or a couple of thousand years ago GP might have been the correct place but today we have Quantum Mechanics, Feynman diagrams and virtual particles, so the answer must be Perhaps. Your 'impentrable walls' deserve further consideration as well. If you heat them with a blowtorch, will they not radiate into the box although no particles pass through?

-

Noether's Theorem and dimensional analysis

Indeed. Perhaps you mean symmetries, relate to conservation laws. In your particular case are you referring to this ? But your question may have nothing to do with the symmetries (and invariances) of this particular transformation. So please provide the context in which you have asked this question.

-

New to chemistry

Well you don't need a fancy laboratory or to spend lots of money. Although you haven't given us much to go on, I hope you already have lots of enthusiasm and an enquiring mind. Chemistry is fun and is about stuff and how it interacts with other stuff. And there is lots of stuff all around you to play experiment with. Starch, paper, soil, oil, water, iodine, air, calor gas, leaves................................... You can start to look at why some are solid, some are liquid, some are gas and some are something in between (eg waxes). What happens when you mix things; sometimes there are changes sometimes not. And some changes are big and/or fast (combustion) some are small and/or slow (staining, corrosion, rusting) I said paper because 'chromatography' - look it up and find out what it means - is a very important technique (Covid lateral flow test) is a very important chemical technique that allow you to do some chemical analysis. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/chromatography-be-a-color-detective/ Electrochemistry is another area for experimenting and finding out, as exchemist has already mentioned. Also growing crystals can be great fun and many suitable chemicals can be obtained from a chemist and kept in clean household jamjars. Some simple (and cheap) instruments might be a pH (acidity) meter (from a fish tank supplier) a Thermometer, a multimeter and a simple U- tube pressure gauge (manometer). Judging from the time of your posting you could be in the bush or outback or other remote place. Also not sure what skills your dad has to help.

-

LongCOVID

Followers of long covid might find thisc ase interesting. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-57586965

-

questions

I think you are kicking a dead donkey. Though you are working very hard, The OP hasn't been back since the day he joined and posted.

-

Why the electron probability density is maximum at the nucleus? (split from Electron Probability distribution)

Which, to quote swansont's comment, is irrelevant. This is about the density of many electrons in materials (look it says so) It for for consideration of metals, semiconductors etc. We are discussing one electron within a single atom. I do accept that there are many similar sounding terms so we should all be careful not to mix them up. It is very easy to fall into this trap.

-

Why the electron probability density is maximum at the nucleus? (split from Electron Probability distribution)

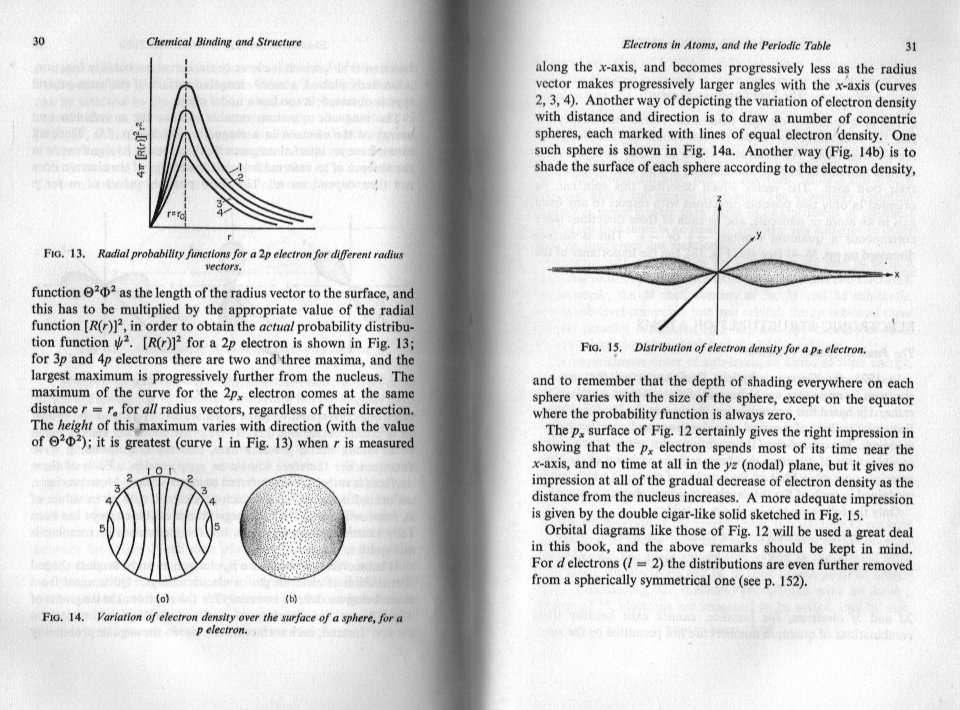

Nor is this a graph of probability density. And it says basically the same as your Khan graph. Both are the result of several pages of working in Maths and Physics. What is the density distribution of the electron ? I have already warned against confusing Probability with Probability Density, they are not the same. Look at the post I just made in Arnav's thread before you answer.

-

Electron Probability distribution

The c curve in your posted diagram is nothing more than simple geometry. (Mathematics) The b curve is nothing more than saying that the wave function or its square are proportional to the (electrostatic) potential energy of a charged particle in the field of the nucleus. This is equated to or calculated by the work to remove the particle to infinity from any given point. Obviously the further from the nucleus, the weaker the field and the less the work that has to be done. This is why the graph tails off to the right. As the particle moves closer to the nucleus and the potential increases because the work to move it out to infinity increases. That is why there is an inverse relationship between potential energy and distance from the nucleus. But the nucleus has a finite (non zero) size and when the particle curve reaches the surface of the nucleus things change so the potential energy does not go off to infinity as a simple reciprocal or inverse relationship would do. However the radius of the nucleus is very small, too small to show on your graph b, Does this also help ?

-

Why the electron probability density is maximum at the nucleus? (split from Electron Probability distribution)

What I find confusing is that I can't see what 'your position' is. I understand that most authors skate quickly over some part of the derivation and also use different terminology that need to be sorted out. For instance your graph from the Khan academy is not a graph of probability density. Nor is it a graph of the quantities shown in arnav's parent thread. It is, and says it is, a graph of probability. In order to understand how your question is handled, it is necessary to be able to distinguish between eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of differential equations as both of these are involved in the principal and subsidiary quantum numbers n, m and l. A knowledge of symmetry, improper integrals would also help. But this is also a case of alternating the Physics and the Maths in the derivation. Authors introduce two different mathematical devices to handle the improper integrals, one is called the Probability Density the other is called the Probability Flux or Probability Current. To understand what is going on you need to start with the physics of the field of the nucleus. Do you know how to do this ?

-

Why the electron probability density is maximum at the nucleus? (split from Electron Probability distribution)

I very much doubt if Wheeler said exactly this. For the very simple reason that a free electron accelerated to 0.85c has quite a different energy from the electron still confined within the gun of the electron source, waiting to be freed and accelerated.

-

Electron Probability distribution

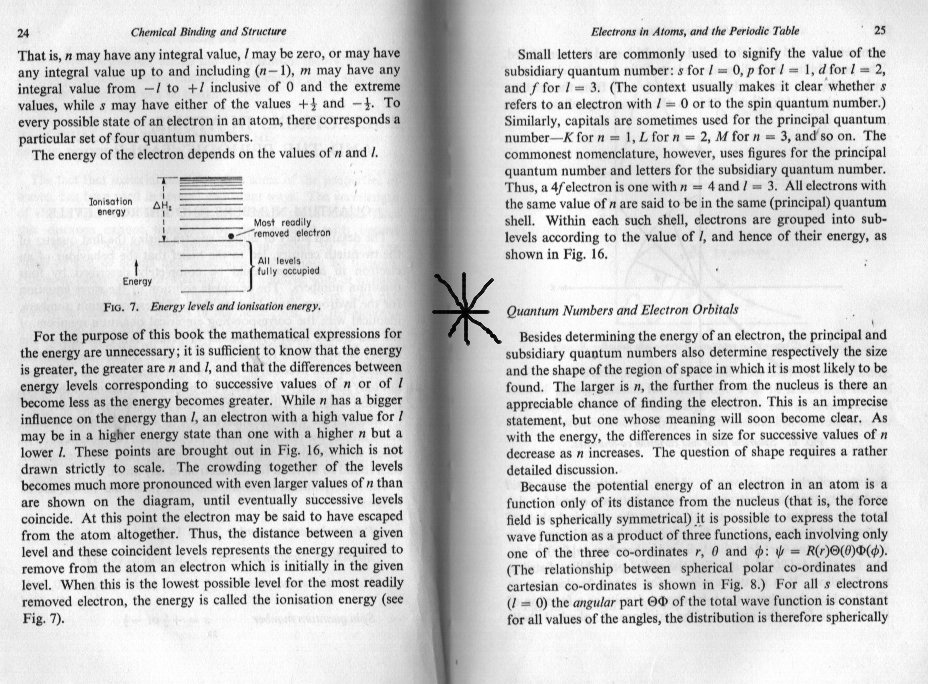

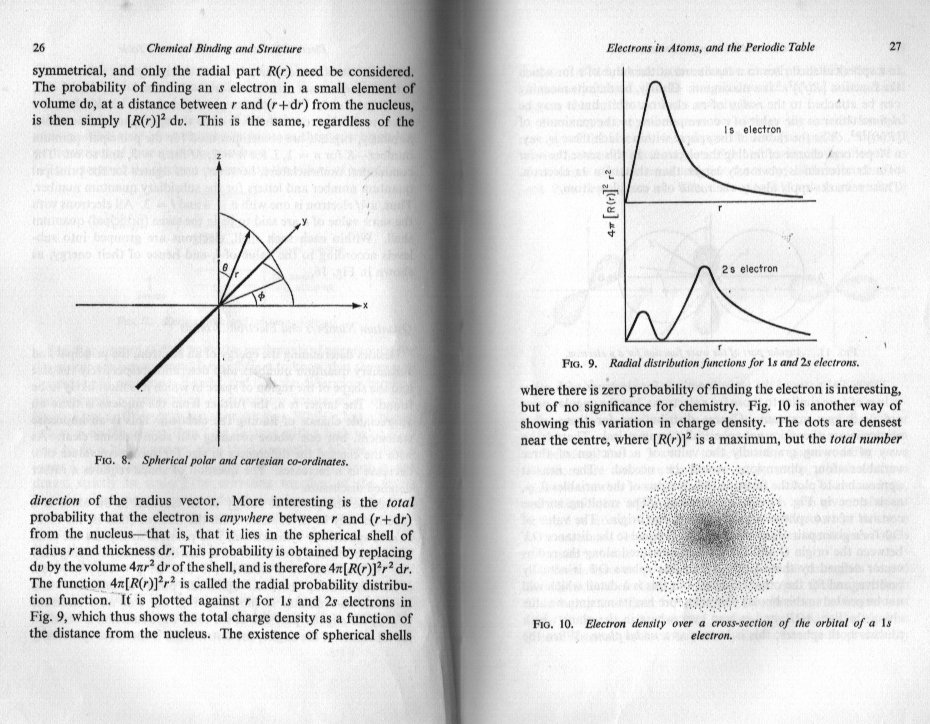

Thank you, excellent answer. +1 Now we are in business. It is not necessary to be super good at differentiation and integration, just to be able to recognise what they are and what the dx and ydx means in ∫ydx One step on from this is to understand the basics of differential eqautions. Consider [math]\frac{{dy}}{{dx}} = some\,function\,of\,x = f\left( x \right)[/math] Which simply says that the derivative is some (given) function of x called f(x). This is all differential equations really are, and the solution or integration of the equation is to find the function of x that yields the given one. That is to find a function of x that when differentiated gives f(x). So rearranging dy=f(x)dx Taking the integral of both sides ∫dy=∫f(x)dx y=F(x)+C Note that variable y includes some arbitrary constant C. F(x) on its own its known as the Primitive of f(x) or the antiderivative. This is the format which you will find in swansont's excellent link to hyperphysics that he gave in his first response. This free site provides an exceptionally clear presentation of Physics and its connections to other sciences and is very well respected. http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/index.html Swansont's link has several itegrals in it, which we can now explain. They are of the type [math]\int {ydx} [/math] Where y and x are different variables. So we need to change one of them into the other in order to evaluate the integral. That is express y in terms of x or dx in terms of y and dy. This format ydx is used when y is a function of x such that y =f(x) that provides a value for y at every point of interest of x. In the case of classical (wave) mechanics our variable y is sometimes called y but often the greek letter phi [math]\Phi [/math] is used and is the classical wave function. In the case of quantum mechanics this variable is psi [math]\Psi [/math] and is called the wave function. Now I have said that the wave function, or its square, is not a probability so the obvious question arises What is it ? More in a moment. But whilst we have both classical and quantum side by side, let us quickly look at your question about hyperfine splitting swansont mentioned. Splitting occurs when there is an additional disturbing or influencing force or field acting on the particle. That is additional to the base force or field that creates the (quantum) energy levels for the particle. For us the particle is the electron and the base field is the (electrostatic) field of the nucleus in which the electron moves. When an additional influence occurs (which may be self generated as with the angular momentum) or may be an external field such as the one in magnetic resonance, The original levels each split into two, one of higher and one of lower energy than the original. These can be further split to form the hyperfine splitting, but that is not really of interest here in my opinion. Splitting more generally is important in other areas such as chemical bonding where the original level splits into a higher level called an anti bonding level (orbital) and a lower level called a bonding orbital. Here the disturbing influence is the field of the second atom involved in the bonding. Splitting also ocuurs in classical situations where we modulate a classical wave with a second wave to obtain new waves of higher and lower frequencies (and therefore energies). OK back to your question and the second part. What is the wave function and what is its connection to probability ? Well a good way to study this is to do a dimensional analysis. A probability is a pure number and has no dimensions. The dimensions of the wavefunction are rather odd because they are not 'fixed', but depend upon the dimensions of the space you are working in. Again swansont has noted this very briefly. In one dimension (x) the wavefunction has dimensions [math]\sqrt {\frac{1}{{length}}} \;ie\;{L^{ - \frac{1}{2}}}[/math] In two dimensions (x,y) the wavefunction has dimensions [math]\sqrt {\frac{1}{{area}}} \;ie\;{L^{ - \frac{2}{2}}}[/math] In three dimensions (x,y,z) the wavefunction has dimensions [math]\sqrt {\frac{1}{{volume}}} \;ie\;{L^{ - \frac{3}{2}}}[/math] So neither the wavefunction nor its square are pure numbers. So they cannot by themselves be probabilities. OK so what do we do about this ? Well the method of dimensions says that if we multiply by two quantities together the dimension of the product is the product of the dimensions. That is dimension (A . B) = dim(A) . dim(B) So if we square the wavefunction to get rid of the square root and multiply by the a length or an area or a volume as appropriate we will obtain a pure number. and the differentials dx, dA and dV have the appropriate dimensions. That is how and why we form one of the integrals [math]\int {{\Psi ^2}} dx[/math] [math]\int {{\Psi ^2}} dA[/math] [math]\int {{\Psi ^2}} dV[/math] Now we have a pure number all that is left to do is to scale it into the appropriate range for a probability that is a number between 0 and 1. This process is called normalisation. This is why the probability must always be associated with a region of linear, aerial or volumetric space. Sorry it was so long and rambling but I hope it helps. F

-

Electron Probability distribution

Hello. The electron can only be at the closer point of the nucleus only on the electronic layer 1 (n1). Its probability distribution being on the layer itself. No? Or do you want to talk about the probability of distribution of the electron on the different electronic layers which would be very important on the layer 1 (at the most near the nuclei) rather than on a higher electronic layer further away from the nucleus? Perhaps you should read what swansont posted before posting confusing material like this. The nucleus has a physical size, so sure. The electron interacts electromagnetically and the fact the the electron can be found there accounts for the large hyperfine splitting of the s state as opposed to the p states, where the wave function has a node, and so doesn’t have nearly as strong an interaction. In alkali atoms the hyperfine splitting of the ground state is hundreds of MHz to >1 GHz, while the excited p-state is significantly smaller

-

Electron Probability distribution

graph (b) that you posted is a graph of 'probability density' against distance from the centre of the nucleus. This is not the probability of finding an electron at a given point on the distance axis. Clearly this would always be 1, if you waited long enough. That is to say the electron will eventually be passing through this point (it will never be stationary there) so if you made your time frame long enough you would always momentarily spot the electron at some time or other. In order to explain exactly what probability density means it would be helpful if you would answer a couple of questions. Have you done enough calculus to know what a derivative (or differential) and an integral are ? Have you learned about mass, length and time as dimensions or units (called MLT) ?

-

Electron Probability distribution

It's a limit as dv tends to zero.

-

Electron Probability distribution

Are you sure you fully understand it ? You book does not say electron probability density or actual probability density on those graphs, which are basically the same as I posted. I basically agree with you, +1 , but there is yet more to it than this, though swansont's terse replies are not actually wrong, just a bit short on explanation which is implied in the physics and maths.

-

What does the ‘infinite monkey theorem’ suggest about the anthropic principle?

Remember we are discussing the proposition that the Universe is not old enough to have evolved the complexity of life we observe. This proposition is supported by a very elementary calculation of the most probably time it would take to type out a simple phrase in English, by hitting the keys at random. No one has yet point out the most elementary flaw in this argument. The phrase being Which has 15 characters. The chance of this occuring as the first 15 characters typed is exactly the same as the chance of it being the (283 x 1018 to (283 x 1018 +15)) characters. So just like the person who wins the lottery with their first ever ticket, the Universe could be lucky and not need to wait at all. I would observe that the central limit theorem does not apply to chemical reaction rates or times.

-

Electron Probability distribution

Here is an explanation with simpler maths than swansont's link that is suitable for high school level. Start reading at the star in the first attachment.