CharonY

Moderators-

Posts

13152 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

144

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by CharonY

-

No one said that it should be. The question is only who is paying and what is the consequence of it. I think I have explained why having students shouldering the cost will drive down education quality. At this point you seem to have a certain thing in mind and keep arguing against that. I.e. you do not seem to follow the arguments being made, I am afraid. You are missing the point. In economic models, salaries increase naturally with productivity. However, in teaching there is a cap. I.e. each teacher can only deal with so many students. Your "perfect" student/teacher ratio would be a hard cap, for example. So let's say there is a linear correlation between productivity and salary. And let's say in the past a teacher teaches 30 students and the worker can produce 100 items. Now moving forward let's say new instruments allow the worker to produce 200 items in the same time. So the worker basically replaces another worker and doubles the salary. Meanwhile the teacher continues to teach 30 students (stagnant productivity) and does not get a raise. Now in yet another decade new technology doubles worker productivity again to 400. Now workers make 4x the salary, but the teachers keeps the same salary. Now, this might not appear to be a big problem, but if many sectors increase productivity (which is a general trend, due to e.g. automation), and therefore most folks make more money, then cost also tend to increase due to overall higher consumption (i.e. inflation). So either teacher wages will have to increase, too (though they tend to trail behind) or they will need to find another job to survive. In Universities professors are usually quite competitive in other job markets (to some degree) due to the skill sets they have. So either universities pay decent salaries (though they have been overall stagnant when inflation-adjusted in many places) or they just take different jobs. The reliance on faculty to teach and the restriction on how many folks can be taught (especially hands-on in applied fields) drives costs up. The one way to deal with it are things like online courses. But as it turns out, the outcomes with this type of learning is usually of low quality.

-

I remember now, it was called "cost disease" or the Baumol effect. Effectively it is because salaries in sectors without productivity gains see salary increases, because they are competing with jobs which do. That being said, there are ideological reasons (and stupidity) which maintains professor salaries still relatively low to their industrial counterparts. Though increasing dissatisfaction seems to drive more folks to seek industrial jobs, even among tenured folks.

-

Here you show a very narrow definition of education: a fiscal exchange for a career. However, education also has the role of broaden horizons, create thinkers, develop a space to solve problems that folks have not thought about, or things that one cannot monetize. I refer back to the competing goals I mentioned a couple of times. Realistically, if a shortcut to a job is all that is needed, the solution is simple. Get rid of education altogether and have corporations set up their own little education enclaves. That way, they can train folks to do exactly what they want. That, however, does not sound much like education to me. That sounds to me like yet another goal. Not only be suitable for a career, but better than another. So you are talking about competitiveness, which creates other incentives. To me a good education is supposed to make the student a better version of themselves and not just better than Dave. INow and I mentioned the complexity of the issue. It is not straightforward in terms of what education is supposed to achieve and therefore metrics are are often imperfect and create incentives that are counterproductive, as I mentioned in my previous post. Just because you measure something, does not mean that you understood the gist of the problem. Finding the right measure is a science in itself. Public funding of universities tend to keep cost down. I can throw a whole slate of data at it showing how private schools are more expensive and how tuition focused universities (even with partial public funding) are usually more wasteful than publicly funded universities. One of the reasons is simple and I mentioned those before. There is only a weak incentive to put or keeps bums on a bench (up to a certain degree). Therefore publicly funded universities have much less overhead in terms of recruitment, student services amenities and so on. In countries like USA and Canada which heavily rely on tuition, the ratio between faculty spending (i.e. cost for professors) relative to administration and support services is roughly 60 vs 40% (and typically worse in private schools). Conversely in public funded universities that ratio is about 70% profs to 30% overhead. In other words, you get more teaching per buck if spend publicly. While there is a "waste" as unsuitable student get into public funded universities, you then have the mentioned weed-out courses which drops the student count over the semesters. In tuition-dependent universities the incentive is to keep the around as long possible regardless of suitability so that they can pay tuition + dorm+ food +gym membership. In other words, it creates incentives that run counter to what folks might consider a good education. I do not think that loans are a good way to go, but instead I believe that universities should have a steady base-funding that focuses on its core mission, rather than just making students (or their parents) happy in order to get their money. Edit: Another piece of information with regard to cost of higher education: The cost will increase over time relative to regular products as there is a cap on how productivity can be increase in teaching relative to product costs. Having a lower ratio between students and teachers is therefore going to disproportionately increase cost, even if overhead is kept down. There is a specific economic term for this phenomenon that eludes me presently. Especially STEM education is therefore expensive and if paid out of pocket, will be prohibitive to low to mid-income families. Public funding is pretty much the only reason why we have an education system rather than education enclaves in the first place.

-

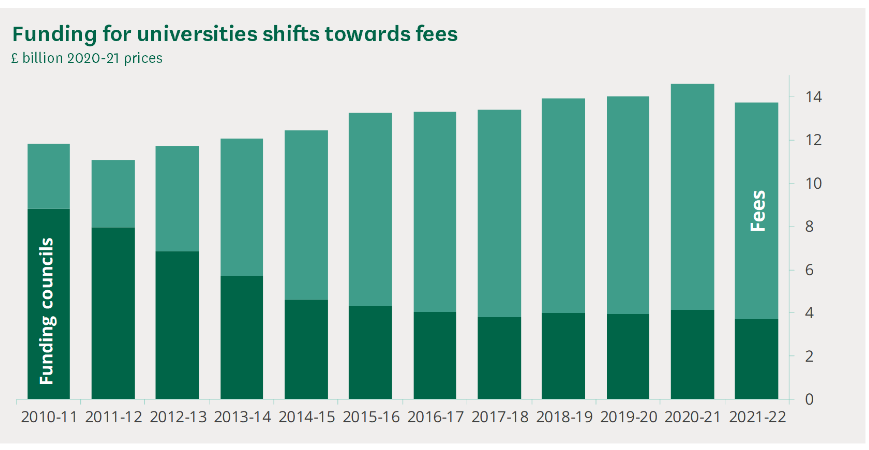

A bit about this one here. I am a bit uncertain what your precise point is, but the University administration tends to be reactive. I.e. when politics changes the situation, they need to adapt to it. Reducing public spending effectively makes them operate more like companies. And at least for faculty it the outcome is obvious: more financial constraints on students, and a shift towards getting more students in, keep them happy and often that goes at cost of teaching quality. In the old system in Germany (which has changed in the last decades, but still remains free), students had only a limited number of tries to pass tests (which were often applied). So it was not unusual that mandatory chemistry classes would result in >60% of biology students to drop or switch degrees within the first two semesters, which more being weeded out in the subsequent ones. These types of failure rates would be considered inacceptable in paid systems, especially nowadays. I am not that familiar with the UK system, but looking at funding trends, I suspect the same issues as in North America. Compared to that, in other European countries 80-90% of the funds are from public sources. The impact of private spending on quality is actually somewhat well documented. The study is a few years old, but the trend has accelerated: Studies have shown that grade inflation is not only tied to marketizing teaching, but it is also related to monitoring teaching itself. I.e. when teaching outcome is tied to teaching evaluation, it provides incentives for teachers to make their lives easier by simply giving out higher grades. Depending on job security and overall system (i.e. pressure from board, administration, students, parents etc.) the outcome may be more or less pronounced. As a consequence, in Germany grade inflation is also observed, but at a lower degree. The suggestions made by OP do appear to try to introduce similar mechanisms into K12 (though, to be fair, they are already on the way) and I just simply cannot see how emphasizing the bad parts of a system is somehow going to end up beneficial. It is mostly disruptive to the few parts that keep the system limping along.

-

I have worked in universities in three different countries with rather vastly different systems. And compared to public funded universities it is harder to find a "good" crop of students when there are financial constraints. Ivy league's are a bit of an exception, but they do have more leverage over their students than other institutions. Which to a large degree is deceptive as it is more an indicator of job situation than the quality of school. Based on which data then? What are the right folks? For that matter, what would be the wrong folks? So learning for exams again. Full circle, I guess.

-

I think you are unaware of the fact that the system is already changing, just not in a good direction. And that the proposed changes are quite similar to what is currently causing issues. I will also add that in recent times, there is a strong urge to be disruptive basically just for its own sake. The tech industry has been leading in that, often without much thought on the consequences, nor measurement of the outcomes. I think there is an overall trend towards superficial but seemingly "cool" solutions, something that I have been also seeing in the science world. Slow, methodical and thorough approaches do not fit the fast-paced trends anymore. And I think that is a problem as the these fast changes also create something like learning amnesia. Same solutions are presented again and again in just fancier packages, but without any substantial improvements. Rather unfortunately, I do see that with students, too. Complex research questions are of low interest, a quick fixes and instant gratification is what folks want.

-

That is at the core of the problem, I think. Education is highly complex and with often competing goals. For example, this is actually the result of treating students as "customers". You see, in systems where Universities increasingly rely on tuition fees, there is also the push from administration to treat students as clients, rather than trainees. As a consequence, higher weight will be given to student evaluations, as the administration wants to have happy clients. The big issue is that students (and parents) do not actually know much about effective knowledge transfer and learning. This is a prime example. Realistically only few students actually get to that point in university, and the rate is dropping. K12 has a lot guardrails which to some degree are needed, otherwise students will be completely lost, but theoretically in university they are supposed to learn to learn without them. Thinking that this is easy, clearly shows a lack of insight into the difficulty of this process. Going back to putting power to the customers: what students really hate are courses that are considered hard and which require applying knowledge as well as working on gaining new ones. What they love are classes that can be passed by memorizing power point slides. There is a clear correlation between grades and ease of course and the resulting evaluation (i.e. how popular a course is). In other words, given the choice, folks will take the easy way. The administration reacts to these desires and force faculty to make things easier to pass more students. And now folks are saying that the degree is not worth anything. Well that is what you get if you do not allow faculty to keep certain standards. Putting even more power to the customers will just accelerate this process. Given the option to work hard in order to gain complex skills and have an easy time but get high grades, you will see most folks choosing the latter and especially over the pandemic, the proportion of the first group (the ones that make teaching fun) are dropping rapidly.

-

Well they might be more careful, but it only means that they are spending money to make money, but not necessarily to educate. Private universities spend relatively more on administration than faculty in private institutions. They spend more on extra-curricular things like recruitment and retention compared to teaching and training. There is a lot of incentive to upsell with amenities (dorms, food court etc.), which bloats the budget for making money. That is not to say that universities are not starting that trend, too (at least in North America, and I believe UK). A big reason is that the governments are either cutting or maintaining educational funds (which, with inflation is the equivalent of cuts), but at the same time try to encourage enrolment. This creates perverse financial incentives for the universities to reclaim the money from students. In contrast, in systems where there are virtually no tuition fees (i.e. state-funded, like in Germany), administrative bloat and waste is minimal and in many ways the educational outcome is better, as students have to do more work themselves.

-

This comment actually demonstrates what I have been talking about. The role of education is fuzzy, with sometimes contradictory goals. Let's start with self-sufficient: what is required to be self-sufficient in a given role? Clearly, the required skill set is very different depending on the job. But especially for young folks, how and when do you know what career they will get into? Careers are unpredictable and often young folks need time well into adulthood to find their path and discover their interests where they want to hone their skills. How does it work if early on a parent decides that certain subjects should not be presented? The second part is universal, but again this is something that many folks do not want. The reasons is that the ability to learn is not easily quizzable and those excelling at it tend to be in the minority. However, parents often think that better grades equal better careers. So it is better for students to only have subjects where they can be easily trained to perform in tests. I.e. there is a desire to remove more complex topics (where you are forced to learn). This is a trend we now start to see in universities, where students have an increasing input on how they want to be taught. Having students/parent pre-determine what they want to learn is similarly bad as having patients determine their treatment. Most do not know what they need or what style of teaching works with them. As such diverse exposure is critical for young minds to find their path. The narrower educations gets, the more likely folks it is that folks will miss their mark. Specialization can only come after folks have a good idea of the the range that is out there. Moreover, learning to learn is the opposite of focused skill learning and it requires the broad exposure as you need to learn to integrate various forms and systems of knowledge, rather than excel in the application of a specialized form. Again, there are contradictory desires and with a presented pathway that is likely to fulfil neither.

-

Not really. You have not addressed what ultimately education should be about. You are saying that practical skills should be taught. Fine, but that is not necessarily what parents want. Right now, in the US there is a movement driven by teachers trying to dumb down students, by limiting their academic exposure to a very narrow view that is in line with their beliefs, but does not really have to have a foothold in reality. It may be something what certain parents want, but it will limit the intellectual capabilities of pupils. Moreover, parents are also likely not competent enough to determine a proper curriculum (which is one of the reasons why some of the demands are questionable). Funding of schools in the US is kind of screwy and compared other countries show more inequity in terms of funding and access to resources. I do not see how any of the suggestions made here would improve that. I will re-iterate that no one really knows what the "product" is supposed to be. Training folks to excel in certain types of tests is too narrow a view. Often the strength and weaknesses of a particular educational journey will only show up years later in life. It is therefore important to open up as many doors as possible for young folks, as no one can predict the path (and it is certainly not deterministic nor can we blame genes for the outcome). At best, the system would create hyperspecialized individuals based on what their parents might have thought to be worthwhile, potentially based on their limited perspective. And I think that this is the opposite of what an effective education should be (whatever we might think of effective). You need to have a broad basis while specialization starts later in University. I would avoid putting young folks on specific trajectories if we do not really know what would benefit them in the future. Adding random indices might provide the illusion of having some sort of objective measure, but if one is not sure what one should be measuring, it is rather useless in the end.

-

Also, in education the desired outcome is not well defined and sometimes contradictory (high grades vs education vs developing skillsets vs developing interests, universality vs elite, etc.). Focus on grades has in many ways resulted in training for tests and grade inflation and folks seem to get stuck on the lower levels of Bloom's taxonomy.

-

Well, the issue that separate system have been in use specifically to avoid overflow, where contaminated sewage can overflow. In areas where weather patterns are shifting, this might become an increasing issue. Essentially what is the best solution really depends on the specific region.

-

Also, with folks directly paying for education (as we can see in university system of a number of countries) there is a stronger incentive for things like grade inflation and student retention.

-

Parents often want that their child specifically rises above the pack. The metric does not really matter, nor the goal to have more educated folks.

-

Storm drains are also not unusual in the UK, but they are often upgraded, newer systems. Here is a wiki article for Brighton, for example https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brighton_sewers, mentioning a storm water collection system. However, they are apparently not entirely separated as overflow from sewer system can get into the storm system. In North America, many sewage and storm system are simply separate pipes as shown in exchemist's link.

-

I think it is a less a national, but more a municipal decision. There are many cities where storm drains are separate from household lines and therefore do not get to the wastewater treatment plants and are released into local waterbodies. You often see are bylaws that e.g. forbid to wash your car because the detergents can get into the storm drains, for example.

-

Lots of issues and there is really something seriously wrong with the publishing culture nowadays. Fundamentally, the rate of research and writing is not possible. I do know especially engineers who are very prolific, but the way it usually works is that they are co-authors, with other folks writing the work and one basically chips in parts of it. So typically one would not be first or last author on those articles. Even if someone else generated all that data, just quality checking and discussing them (which is your duty as the corresponding author) will take more than 37 hours, not to mention the time it takes to actually write it. The only way it can in theory work is that they are all basically the same paper, just with e.g. substrate or catalyst exchanged, or something simple like that and or there are hundreds of folks working for him and he just signs off on finished manuscripts without checking. Heck, just getting the signature of all co-authors can take longer. And this is without touching the issue of affiliations, which should be fairly straightforward under normal circumstances. This here looks rather sketchy.

-

I am not sure why you think folks are rejecting it. As mentioned, once living standards and education (especially among women) improves, fertility drops. Even one-child policies seemed to have little immediate impact (according to studies), but seems to accelerate the decline once fertility drops below a certain threshold (as we can see in China). Most industrialized nations have low fertility, which results in other economic issues related to an aging population. So the current assumption is that we will hit somewhere between 11-12 as a max and afterward the population will mostly naturally decline. What would be an alternative in terms of sensible pop control?

-

No, it was mostly just trying to make clear that my point was not an either/or situation when it comes to population size vs emission. I integrated the earlier mentioned point within this thread that female empowerment is one of the most important factors related to reduction of fertility. I also mentioned that the examples are certainly not perfect, but the point is that there is marked inequity in terms of emissions. North America has a poor track record in terms of energy efficiency, for example. Considering the temperatures in Canada, you would think that homes are extremely well insulated, yet often they are not and energy consumption is high. In Europe, there are many initiatives promoting energy efficiency, fuel efficient cars etc. In Canada, many people use trucks as their daily drivers and certain high-efficiency appliances are really hard to get. While it would take considerable effort to figure out all the details, various industrialized countries have cut down CO2 emission from their peak levels by up 60% over several decades with increasing or maintaining population size. With modern technology, that likely can be accelerated. The same cut cannot be achieved by population control over the same time (without culling, that is).

-

As mentioned before, this line of thought is a bit too one-dimensional. For a given lifestyle, there is a range of e.g. associated CO2 emissions. High-income countries like Sweden and Switzerland, for example emitted about 4.5-4.7 tons of CO2 per capita, compared to 17-18 for Canada and Australia in 2016. For a very silly back of the envelope calculation we see that the average per capitaCO2 emission worldwide was 4.79. So theoretically, if the whole world consumed like Sweden/Switzerland, the total emissions would actually go down. Now, there are of course numerous practical issues with that, but it shows that how and which resources we use has a huge impact. Of course population has an impact, but reducing emissions has arguably more practical ways to be addressed in the short and mid-term. That does not meant that education and empowerment for women is not important, it certainly is and has strong impact. It is just that it is a long-term process (https://www.gapminder.org/topics/population/fill-up/)

-

Given all the same parameters of course a smaller population has likely fewer emission, though it would depend on other factors, too. Things like travel and energy use can be big factors. Canada has about four times the per capita emission of Switzerland, for example. This is of course an imperfect comparison as in a globalized economy carbon emissions can be outsourced, but at least taken at face value, 3 billion Canadians would produce as much as 12 billion Swiss folks. That would cover the range from the proposed 3 billion sustainable population to the likely maximum population that we are going to see. To be fair, most folks do not like substantial changes in their day-to-day. Folks railed against simple measures like seat belts and masks. Having to have to change habits or convenience in any sudden way usually results in sever pushback, and this is often something folks with power can leverage. Things change either slowly, require legislation or have to freak out folks enough that they are willing to do something. A level-headed cost-benefit calculation only seems works for some folks some of the time.

-

Oh, don't threaten me with a good time. Perhaps Disney will send in Basil to solve the murders!

-

It is actually a thing: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_lives_clause as to address rules against perpetuities https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rule_against_perpetuities.

-

I think the original argument was worse, as it appears that the claim was that the natural sciences had to be hundreds of years old to be valid. This is of course silly as modern methodologies and theoretical frameworks have shifted especially in the life sciences, with rather few concepts being several hundreds years old (but still heavily modified). But that all being said, climate science is actually fairly old though it was not a separate science. Mathematicians and physicists like Fourier and Tyndall looked at factors affecting Earth's temperature back then, for example. I think most environmentalists, activists, but also climate researchers would agree with you. There was economic argument that starting earlier would have been way cheaper, but we sat on our collective arses until things got really urgent. Generally speaking, politicians do not like big changes as they (similar to companies) dislike uncertainty. Up until it is certain to be bad, so they are forced to make some moves. It is a tragedy of commons all over, and denial seems to be one of the few ways to feel good about it. But not to sound too fatalistic, one could argue that some movement is better than no movement.

-

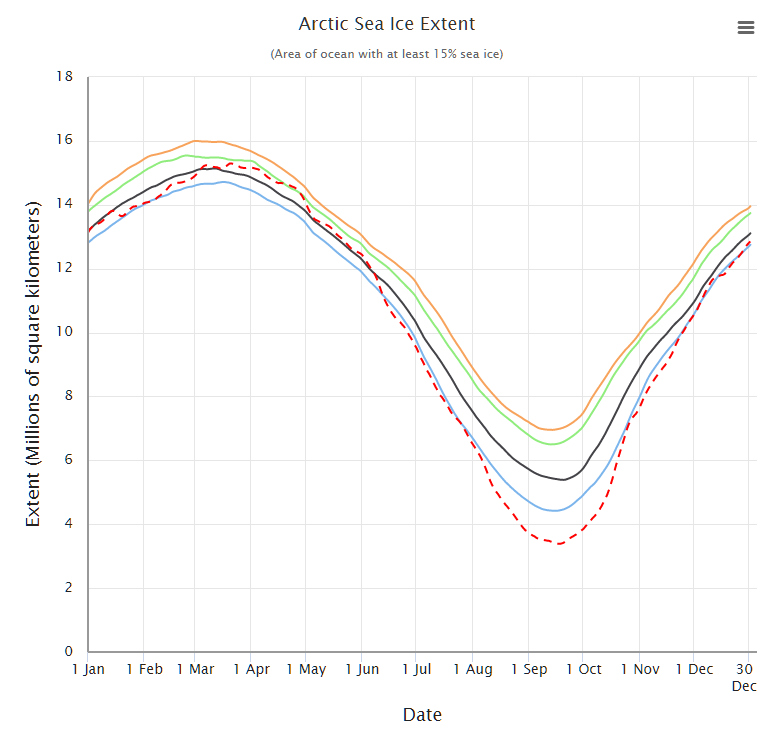

That is the thing, one would normally not just eyeball things arbitrarily but one can calculate trends. And if one look at the calculations associated with the graph, it is shown that that the current shrink rate is about 12.6% per decade. Visually, the 2012 data point is misleading as it has huge drop which kind of makes the subsequent movements more shallow. Basically the fluctuations (or noise) in the system makes eyeballing trends difficult. A different way to look at the same time is to add more months and then plot averages over several decades , which smoothes out things a bit. Here you can see that especially starting around 2001-2010 not only the overall loss was quite a bit steeper, but also that recovery did not reach previous levels anymore, resulting in an increased net loss (red dashed line is the aforementioned extreme case of 2012). That being said, the situation is likely more dire, as newer methods including measuring the depth of ice (as these are only measuring the extent) suggest that the ice is also getting thinner. So the volume of ice lost, is actually a fair bit higher.