-

Posts

2140 -

Joined

-

Days Won

62

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by Markus Hanke

-

Time and relativity (split from The Nature of Time)

Markus Hanke replied to DanMP's topic in Relativity

No. It’s not. You are asking about relativistic motion through a gravity well other than the Earth’s, and electromagnetic radiation propagating to/from Venus, Mercury, as well as various probes we have sent out, provides a perfect example for that. -

Aphantasia is not a real condition

Markus Hanke replied to ArtsyGirl's topic in Psychiatry and Psychology

This thread is just bizarre, to be honest. I am autistic, and have been involved in the neurodivergence community for quite some time, both on a local and an international level. Aphantasia is a relatively common comorbidity for people on the spectrum; I personally know 3 (maybe 4) fellow autistic people who have this, and my social circle is by no means large. Even among the general neurotypical population, this isn’t rare - there has been a study conducted on this only a few months ago: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053810021001690 Evidently, aphantasia and its opposite - hyperphantasia - are very much real. Claiming otherwise isn’t just ignoring the evidence, but - and that’s much worse - it is dismissing and invalidating the suffering and challenges of those who have it, because this has a very real impact on people’s lives. -

You are also assuming a ruler when you draw out your 3D coordinate system. Yes, it is different - that’s what I’ve been attempting to demonstrate in that graphic I provided earlier. A clock provides an additional degree of freedom that uniquely specifies the evolution of the system. It’s extraneous information that removes the ambiguity inherent in a 3D-only graph of your system. Mathematically speaking, a time axis is orthogonal to each of the three space axes, so time “information” is linearly independent from the spatial hypersurface. You do not seriously propose that we can just do away with time in all our physics models and expect it to still work out correctly, do you? Surely you can see that this doesn’t work. If all the available dimensions are spatial in nature, and there is no other external information, how will there be “change”?

-

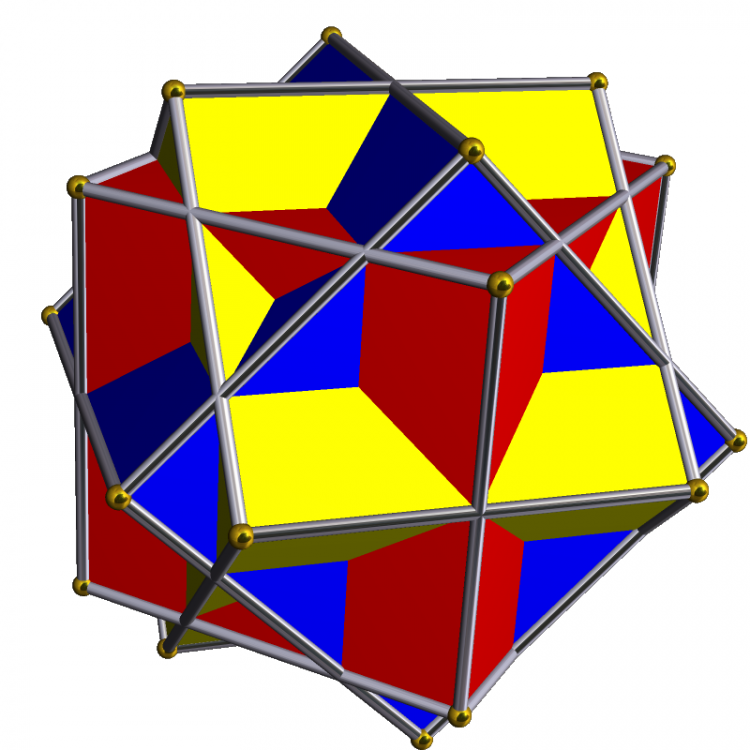

Have a look at the following situation: this is a plot of a 3-cube that has evolved in time, but instead of using a time axis, the evolution is all plotted on the same 3D volume to just reflect “movement” (as you suggest), without reference to an external “time” at all. The movement/change here is a combination of rotations (angle not necessarily constant, and rotations not necessarily in the same direction), and a change in colour. Without being given any information other than points within that the same 3D volume (ie only the above picture), can you tell me what the initial state of this system is, and how it evolves? What in here corresponds to past, present, future? You can’t do this, unless additional information is provided that is not itself an element of this same 3D volume. I think you can see the issues. And this is an idealised evolution in just three discrete steps - real-world systems, especially classical ones, feature continuous evolutions, with rotations around all three axes. Try to plot that into a single 3D volume, and what you’d get in the continuum limit is a solid ball - you couldn’t even tell the original shape any more. On the other hand, if you were to plot the evolution of the above system on a clearly labelled time axis with separate 3D plots at t=1,2,3, then there are no ambiguities at all - you can tell exactly what the original state was, and how it evolved in time.

-

Time and relativity (split from The Nature of Time)

Markus Hanke replied to DanMP's topic in Relativity

I don’t see how this is different from the Shapiro delay, which has been tested extensively in a variety of ways. -

This is true, though I meant something different - my argument was that eliminating time as a dimension will reduce the dimensionality of the spacetime manifold to 3D+0, so that the indices in the field equation now only run over a range \(\mu,\nu=1…3\). If you do this, then the Weyl tensor vanishes identically, and, because the vacuum field equations also imply \(R_{\mu\nu}=0\), you are left with both the trace and the trace-free part of the Riemann tensor vanishing. In other words, spacetime must be Riemann-flat everywhere in vacuum. So in 3D+0, assuming validity of GR implies that there is no gravity between massive bodies in vacuum.

-

Ok, point noted - though I did make it quite clear that this refers to general transformations between frames, and not just composition of velocities. They were just meant to be general Lorentz transformations, and I left the parameter unspecified. I don’t think it matters what kind of parameter you choose - speed, angle, gamma factor etc -, since the transformation itself always remains linear; it acts on 4-vectors and general tensors, not the parameter itself.

-

Actually, I formulated this badly - GR does still work, even if you take out time as a dimension. The problem is just that the kind of gravity you get then is nothing like the gravity we actually see in our universe.

-

If U is a 4-vector, then the formula for a Lorentz transformation from the original frame to some primed frame is written as \[U’=\Lambda(v)U\] where \(\Lambda\) is a square matrix, the Lorentz transformation matrix, and v is some parameter of the transformation (not necessarily speed!). I invite you to verify yourself that \[\Lambda(v+u)=\Lambda(v)+\Lambda(u)\] and (c=const.) \[\Lambda(cv)=c\Lambda(v)\] by whatever means you find most convenient. The above two relations define the property of linearity in the context of matrix transformations. So yes, the Lorentz transformations are indeed very much linear - as of course they have to be, since they map lines into lines, ie inertial frames into inertial frames. This is pretty trivial tbh. P.S. Cross posted with joigus, studiot and Grenady! Had my reply open on screen some time before hitting “Submit”.

-

Yes, unfortunately you are right. I see a lot of problems with the way physics is presented in various media. Sadly this appears to be true across the board, including the other sciences too. I think they meant explaining the model itself, rather than any underlying ontology. Well, relativistic effects are always relationships between reference frames, so this is not really a surprise. But the true power and beauty lies in the exact opposite - that relativity allows us to write the laws of physics such that they do not in any way depend on which reference frame is chosen. It’s about the fact that nature appears to be generally covariant (within the classical domain) and thus does not care about observers at all. That’s a powerful symmetry.

-

Yes, and this is true for all clocks - including the distant stationary one! Now think about this - if the distant stationary clock measures purely its own time (“behaviour”), as you correctly say, then why do you expect it to be able to accurately measure any process that does not, in fact, take place within its own frame? Can you see the issue? The reverse situation is just as true - the in-falling clock cannot, based on its own readings, expect a distant stationary clock to tick out the same amount of time. Exactly! This is just the basic principle in GR - the laws of physics are covariant, so all observers agree on them. In this case, all observers agree that the in-fall world line does in fact intersect the horizon, including the distant Schwarzschild observer. He just doesn’t physically measure this on his own clocks and rulers, because those are inextricably linked to his distant, stationary frame, and thus unable to measure anything about the in-falling particle. They can only measure things in their own local frame. There are two entirely separate concepts to consider here - there is the manifold, which is spacetime itself, ie the set of all points in space at all instances of time (“events”); and then there is the coordinate chart that covers the manifold, which is simply a map that assigns a unique label to each event. The manifold is like the physical set of streets that makes up a city, whereas the chart is the choice of names we assign to those streets. It should be obvious straight away that the choice of street names is entirely arbitrary (so long as they are unique) - we can erase and re-write all street names, without affecting any of the physical layout and geometry of our city. You can also have different people employing different names for the same street; there’s potential for confusion when you do this, but so long as both sets of names are unique, there will be no problems or contradictions; you can map them into each other 1-on-1 in a unique way. The time it takes you to drive from one address within the city to another is not affected by the way the streets are named in any way. Essentially, the street names have no physical significance so far as the layout of the city is concerned. And so it is with spacetime - you’ve got the spacetime manifold and its geometry, which is given by the distribution of gravitational sources (“the city). This is entirely separate from the coordinate chart which you choose to label each event on that manifold (“the street names”). How long it takes to inertially free-fall from one event to another as measured on a co-moving clock is likewise not affected in any way by what kind of coordinate chart you choose to use. Just as is the case for the city, the choice of coordinate chart has no physical significance whatever so far as the geometry of spacetime is concerned. What happens at the event horizon is that the Schwarzschild coordinate chart becomes singular, in the same way as spherical coordinates become singular at the poles on Earth. So the question then becomes whether this is purely a coordinate singularity, where only the coordinate chart fails due to the way it is defined, but the manifold itself remains perfectly regular; or whether this is a curvature singularity, where both the coordinate chart fails and the manifold ceases to be smooth and regular. The former has no physical significance, it’s just an artefact of the way we choose to label our events; whereas the latter means that the manifold is geodesically incomplete, ie we cannot physically extend free-fall geodesics past that region. The simplest way to distinguish between them is to try and cover our spacetime with a different coordinate chart (remember that this choice is arbitrary and has no physical significance!), and see what happens at the horizon. Instead of Schwarzschild coordinates we can use (e.g.) Gullstrand-Painleve coordinates, Novikov coordinates, Eddington-Finkelstein coordinates, Kruszkal-Szekeres coordinates, or any other convenient choice. If we can find even only one coordinate chart that remains smooth and regular at the horizon, then we know that the original singularity was of the coordinate kind, and thus has no physical significance so far as the manifold is concerned. And that’s indeed the case here - in Schwarzschild spacetime, there are many coordinate choices that remain smooth and continuous even at the horizon. To be absolutely sure, we can also check in a more direct way, by considering a covariant quantity that does not depend on coordinate choices, such as the curvature tensors. More specifically, one looks at the principle invariants of the Riemann tensor and the Weyl tensor, which indicates how the curvature of spacetime behaves at the region in question. There are altogether five of such invariants. When we calculate them at the horizon (using any coordinate chart of our choice), we find that they are all finite and well defined, indicating that spacetime is smooth and regular there. This is in contrast to the central singularity - no matter what coordinate chart we choose, the central singularity is always singular; we cannot eliminate this by choosing different coordinates. Also, the curvature invariants all diverge there. This indicates that the central singularity is a physical one - a region of true geodesic incompleteness. There are other ways to distinguish these singularity types, but you get the idea - the event horizon is a coordinate singularity (no physical significance), whereas the central one is physical.

-

No one knows the answer to this. There is also the far less intuitive possibility of the “tower” being quite finite, while at the same time lacking any irreducible ontology. Rovelli’s relational interpretation of QM would be an example of this. I don’t think so either - though of course we can’t be sure. I don’t think the principle of relativity can be derived from any fundamental axioms - it’s an empirical observation about how the world works. We simply don’t see any variations in the laws of physics between observers, at least not within the constraints of our experimental abilities. You can never “absolutely” prove any model of physics. We can, however, but upper bounds on the magnitude of any possible Lorentz-violating effects, and these bounds are very stringent indeed. The laws of acoustics are just a special application of the laws of fluid dynamics - and those can be written in fully covariant form using the energy-momentum tensor, so they don’t depend on the observer. Based on that you could, if you wanted to, write a model of relativistic acoustics that is observer-independent. Yes, there are very many tests of Lorentz violations, both historical and modern, and none of them has ever found any hint of such a thing in fact existing. Like I said, this places very stringent upper bounds on such violations. Yes In the rest frame of those very same ultra-high-energy cosmic protons you just mentioned, my computer does in fact operate at those very speeds. What do you mean you “don’t buy it”? Do you doubt that the mathematics provide the correct answer when you run the numbers? It’s rather easy to show that they do in fact work out, in a fully self-consistent way. Once again, Minkowski spacetime here is a descriptive model, the purpose of which is to provide a framework to make predictions for real-world scenarios. And it evidently does this really well. Of course, it has no explanatory power as to why this model - as opposed to some other description - works so well. Here’s where we come back to the question as to how fundamental (or not) spacetime is, and what, if anything, underlies it. These questions don’t as yet have an answer. You appear to be using a different definition for the term “geometry” than mathematics do. Intuitiveness is not a required feature for any aspect of mathematics or physics, or any other science for that matter. It just needs to work, and be internally self-consistent. Euclidean geometry seems nice and intuitive to you only because as being human you happen to experience a domain of the universe that is roughly Euclidean in nature; this does not afford it any physically privileged status, however. Non-Euclidean geometries are equally well formulated and understood, and are equally self-consistent. Besides, intuitiveness is highly subjective - to me, for example, Minkowski space seems perfectly natural, and very well suited for the task at hand.

-

That’s a contradiction. Time in GR is a dimension - if you don’t include it as such, the model no longer works. It’s a statement about time being critical to classical gravitation, ie General Relativity. You simply cannot eliminate time as a dimension, thereby reducing the dimensionality of the universe (in the classical domain) to 3, and still expect GR to provide a model of real-world gravity. That being said, the question as to what happens once you go beyond the classical domain, into semi-classical and ultimately quantum gravity, is interesting and quite valid. Some candidate models for quantum gravity do hint to time/space, or some combination of these, not being fundamental but in some sense emergent. This is very much speculation, though.

-

On Earth, the standard lat/long coordinate chart we are all commonly using for navigation is singular at both poles. Does this mean the poles do not physically exist, or that there is a physical singularity located there? Does this mean that our models of aeronautical navigation “break down” there? Evidently it means no such thing. There are simple, standardised ways to tell apart physical singularities from coordinate singularities on differentiable manifolds - these issues really have nothing to do with GR at all, they are mathematical questions that are considered in-depth within the discipline of differential geometry. It is trivial to show in a fully coordinate-independent way that the event horizon is not a physical singularity, in the sense that the manifold (which is entirely different from the coordinate chart) is completely smooth and regular there, and everywhere geodesically complete. You’ve got this exactly backwards, I’m afraid. The length of a world line is a quantity that all observers agree on. If an in-falling observer finds his world line to be of finite length, then all other observers - including the distant stationary one - will also agree that it is in fact of finite length. This physically means that everyone agrees that the in-falling clock reaches (and crosses) the horizon in a finite amount of time as measured by itself, since the accumulated time on this clock is by definition identical to the length of the world line it traces out. On the other hand, what the distant stationary clock shows (divergence to infinity) is not the length of the in-fall world line, so it is entirely irrelevant to the physical outcome of the in-fall. You cannot use a distant clock to argue local physics, so it is really the distant clock that doesn’t matter, and not the other way around.

-

Ah I see, sorry, I misunderstood you then. You are right of course, in GTG gravity isn’t formulated by means of spacetime curvature. Ok, that’s fair enough. And you are right - some models do go deeper than others, in that sense. So the question then becomes whether there is a “rock bottom”, ie a set of irreducible elements that make up reality on the most fundamental level; and what those elements are. In contemporary physics the most fundamental “ontology” in this sense is spacetime, and the quantum fields that live on them. Personally I think neither of these are irreducible, and will turn out to be approximations to something more fundamental. Yes, absolutely! It’s not just useful, but essential. This is why there is so much active research going on in the area of quantum gravity. There have been attempts to model (classical) gravity entirely without recourse to any notion of “spacetime”, flat or otherwise. One such example is Geroch’s “Einstein Algebras”: https://projecteuclid.org/journals/communications-in-mathematical-physics/volume-26/issue-4/Einstein-algebras/cmp/1103858122.pdf Then of course there are various candidate models for quantum gravity that do not take classical spacetime as primary and fundamental, such as Loop Quantum Gravity, or Causal Dynamical Triangulations, among others. I’m struggling to wrap my head around this - the principle of relativity in its most general form ultimately just boils down to the observation that all observers experience the same laws of physics. My laptop works in my living room in exactly the same way as it does on a spaceship travelling close to c, or someplace very near the event horizon of a BH, because all laws of electrodynamics, quantum physics etc are exactly the same in all frames. This is as much an empirical observation as it is a matter of logical consistency - to me it is completely natural to such a degree as to be almost trivial in its simplicity. Why does this principle bother you? Again, I am genuinely curious to understand where you are coming from with this (we both already know the experimental evidence, so that’s not the point here). And so am I Yes! I think this is a crucially important point, though I am unsure of the “inescapable” bit. It is inescapable in the sense that our direct experience - and thus the reality-model our brains construct - can never be anything else but human. However, it is possible to overcome these constraints by building mathematical models of the world that are not subject to the tacit assumptions our brains impose on us. For example, there are candidate models for quantum gravity that do not assume “space” and “time” to be primary and fundamental constituents of reality; just by being able to build and comprehend such models, we go beyond the constraints of human-centred reality.

-

…which is a geometric model itself, with g=diag(-1,1,1,1). GTG uses a pair of gauge fields (corresponding to translations and rotations) instead of the metric as its fundamental entity, and employs the formalism of geometric algebra to build the model. To me, that’s very much geometry - the clue is even in the name. That’s fair enough. But it does bring us back to the previous point about what it actually is we are trying to do here - I maintain that in physics we simply make models of aspects of the world. GR is a model of gravity that happens to employ Riemann geometry as its language; but to me that does not imply that that aspect of the world “really is” geometry in an ontological sense. It implies only that the particular formalism employed by GR shares the same structure and behaviour as real-world gravity, and thus it is a useful model, akin to a map. It also does not imply that the standard formalism of GR is the only possible way to draw a map of gravity - it evidently isn’t. P.S. I always use the word “ontology” in the sense it is employed in philosophy. That’s strange, since your earlier comments implied that you had no objections to Minkowski spacetime as the basis for GTG. Besides, GR reduces to SR everywhere in small local regions, so saying that SR bothers you more than GR is…well, strange. I agree with most of this, except the comments on ontology. It is a serious and important discipline, but to me it is not what physics is primarily concerned about. Though of course, there is a certain amount of overlap. Yes, this refers specifically to the Einstein-Rosen bridge that appears in standard GR in the maximally extended Schwarzschild spacetime - this feature does indeed not appear in GTG. However, we need to remember that a “wormhole” is a general term for a class of topological constructs that lead to spacetime becoming multiply connected in some way; there are many different types of these, and not all of them require singularities. I do not believe that GTG actually guarantees spacetime to always be singly connected, but I’m open to correction on this one.

-

P.S. I’m genuinely curious - why does this particular model resonate with you more than GR does? They are both geometric models, but GTG relies on much more abstract underlying entities (gauge fields). At least the metric in GR directly connects to real-world measurements of times, distances and angles, which is a very “hands on” kind of thing…whereas gauge fields are really very mathematical ideas, and don’t correspond to anything even remotely as practical as aforementioned measurements. From your previous comments here I would have thought that you’re not in favour of overly mathematical concepts. Just wondering

-

Feymann Integrals handy reference sourcebook

Markus Hanke replied to Mordred's topic in Quantum Theory

Do you seriously call this 800+ page tome an “article” Great resource though +1 PS. Why does the upvote I just gave you appear in red, instead of green? I’ve never seen this happen before… -

You were originally referring to “19th century principles of science” - which were based on a Newtonian world view. And even back then, people were already aware of numerous problems and issues that didn’t fit that world view. No, it is an honest appraisal by someone who reads a lot of papers on these subjects. So are all the other theories, so you’ll have to give them the benefit of the doubt too. Yes, GTG is a specific example of a gauge theory of gravity, as opposed to a metric theory such as GR. It can be shown that there are, in fact, infinitely many such theories, all of which describe propagating 2-polarisation states of gravitational radiation, and which resemble GR (no spin) or Einstein-Cartan gravity (spin) under the appropriate circumstances. Within the domain that we can experimentally test and observe, these models are generally distinguishable from GR only insofar as they don’t contain any equivalence principle - therefore testing the equivalence principle is a good first step in testing for gauge theories of gravity. At present, no violations of the equivalence principle have been observed, not even in the strong field domain (BH mergers etc). This doesn’t invalidate all gauge theories, but it does constrain the form they can realistically take. There is another critical issue with this, however - because gravity now also couples directly to spin (unlike in pure GR), these theories introduce extra terms into the Dirac equation. These extra terms are too small for us to be able to experimentally detect them right now, but they would become important in the strong field regime. Again, I am not aware of any indications that such phenomena have been observed anywhere. As for exotic phenomena - these gauge theories exclude the possibility of singularities, even in the classical domain, which is definitely good. Wormholes are not categorically excluded though as far as I know, where did you read this? Note sure about CTCs, but it’s possible that these don’t occur, since no ring singularity forms. I personally like gauge theories of gravity, since the basic approach is very elegant, and there are no immediate conflicts with available data. I’d say that out of all the various alternatives (or rather: extensions) to GR, these are probably the most promising. I would say, though, that what we need isn’t an alternative to GR (unless some data becomes available that is in direct conflict with it), but rather a generalisation of it. But that’s only (sort of) true for ordinary non-relativistic QM, which is just a simplified approximation. Full quantum field theory is based on fields and their interactions, not particles. I have no idea what you mean by “unscientific” - both SR and GR are fully amenable to the scientific method, irrespective of the precise mathematical details of these models.

-

They remain valid - within their respective domains of applicability (which is why we all learn Newtonian physics in high school). The issue was that these domains turned out to be limited, and if you go beyond them, you need different physics. This is why relativity, QM, and (later) QFT came about. Alternative theories of gravity are legion, and the author(s) of each and every one of them generally insist that theirs is the only correct one, and solves all of GR’s problems. You need to take such claims with a huge grain of salt. What often happens is that these theories might match the data for one particular phenomenon very well, but then fail to do so for other aspects of gravity; or, which is worse, they flat out contradict some other aspect of known physics or observational data. For example, the model in the link you provided does not seem to be locally Lorentz invariant (AFAICS) in small regions if the extra parameters are anything other than identically zero - which is a huge problem, since local Lorentz invariance has been tested for to extremely high precision, and no preferred coordinate frames have ever been found. If you compare all the currently known models for gravity against one another, then GR still remains both the simplest model, as well as the only one that matches all available experimental and observational data very well, so far as classical gravity is concerned. Have a look here for quick introduction: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alternatives_to_general_relativity This being said, it is, I think, safe to assume that the domain of applicability of GR is itself also limited. I just think that whatever more general model underlies GR (to which GR will be the classical limit) will involve a paradigm shift far more radical than just adding a couple of extra terms to the gravity Lagrangian; my guess is we’ll be in for a complete overhaul of our understanding of what “space” and “time” mean on a fundamental level. If you feel the shift from Newtonian to relativistic and quantum physics was too radical, then I don’t think you’ll like what I think is coming

-

The wording is somewhat misleading. What happens is that, once the horizon is crossed, ageing into the future always corresponds to falling down radially - in other words, you cannot maintain a constant radial position, nor can you go radially upwards, irrespective of how much downward thrust you try to exert. Even photons must always fall down. Hence, space and time enter into a relationship whereby any ageing into the future must necessarily and always lead to a decay in radial position - and since ageing into the future is inevitable, so is falling further down into the BH. Because this is a relationship between space and time, you cannot cheat your way out of this situation by trying fancy tricks of motion (like slingshotting around the singularity etc) - it doesn’t matter at all how you move, you will, on average, always fall radially downward as your clock ticks into the future. If you were the free-fall body, you wouldn’t notice anything special as you fell. It’s only once you try to arrest your fall or get back out by firing thrusters, that you would notice that you are in fact unable to do so.

-

Well, that happened because those 19th century principles turned out to not work so well - or rather, they only work well under a very specific and limiting set of circumstances. Thus it was necessary to find better descriptions of the world around us.

-

You really don’t need to bang your shinbone on a stool that’s not in the way. The answer is simply that it measures the fact that a period of time has passed. This is in no way philosophically problematic, precisely because we don’t equate “time” with any specific clock mechanism. It’s only if you try to redefine physical time as “movement”, as you suggest, that you end up with all sorts of philosophical, mathematical, and physical issues and tautologies, because that’s simply not a good model of the world around us - there are plenty of specific examples of systems evolving without any “movement”. The crucial point here is that this is true for all clocks, entirely irrespective of what their internal mechanisms actually are. A digital wrist watch, an atomic clock, a decaying elementary particle, or the flipping of spins all show the same fact that time passes (ie that systems evolve and age into the future), and that this is entirely separate from any specific mechanism used to measure it. It’s as true for periodic motion as it is for motionless systems. You can see this even more clearly when you compare clocks by placing them at different points within a gravitational field - gravitational time dilation affects all clocks equally, irrespective of their internal mechanisms (or lack thereof). A vastly more interesting and pertinent question is whether - and in what sense - time (and also space, for that matter) is fundamental to the universe, or whether it is emergent from something more fundamental that is not in itself spatio-temporal in nature. This is still an open question, and very much subject to debate within the physics (and philosophy) community.

-

Because the human condition doesn’t magically end with the surface of our skin. We are a part of the universe, and thus ultimately a product of its origin and all the various processes that have been going on since then. It is delusion to think that we are somehow separate from everything else, so that these questions have no relevance to us. Understanding the universe means understanding ourselves and our human condition better. Also, the question carries connotations that the value of something is defined solely by the financial benefits it yields. This is another common delusion. Too many people these days confuse the price of things with their actual value, which isn’t always readily quantifiable, nor even commonly recognised. But I think it’s also important to realise that not everyone will “get” this, no matter how well you try to explain it, and how good your arguments are. Sometimes you just have to leave them to it, and move on.

-

The one that comes to mind is “Helgoland” by Carlo Rovelli; I found it to be a very good read. Do bear in mind though the final conclusion of the book does promote his own interpretation of QM, which is Relational Quantum Mechanics. But the historical overview is quite good.